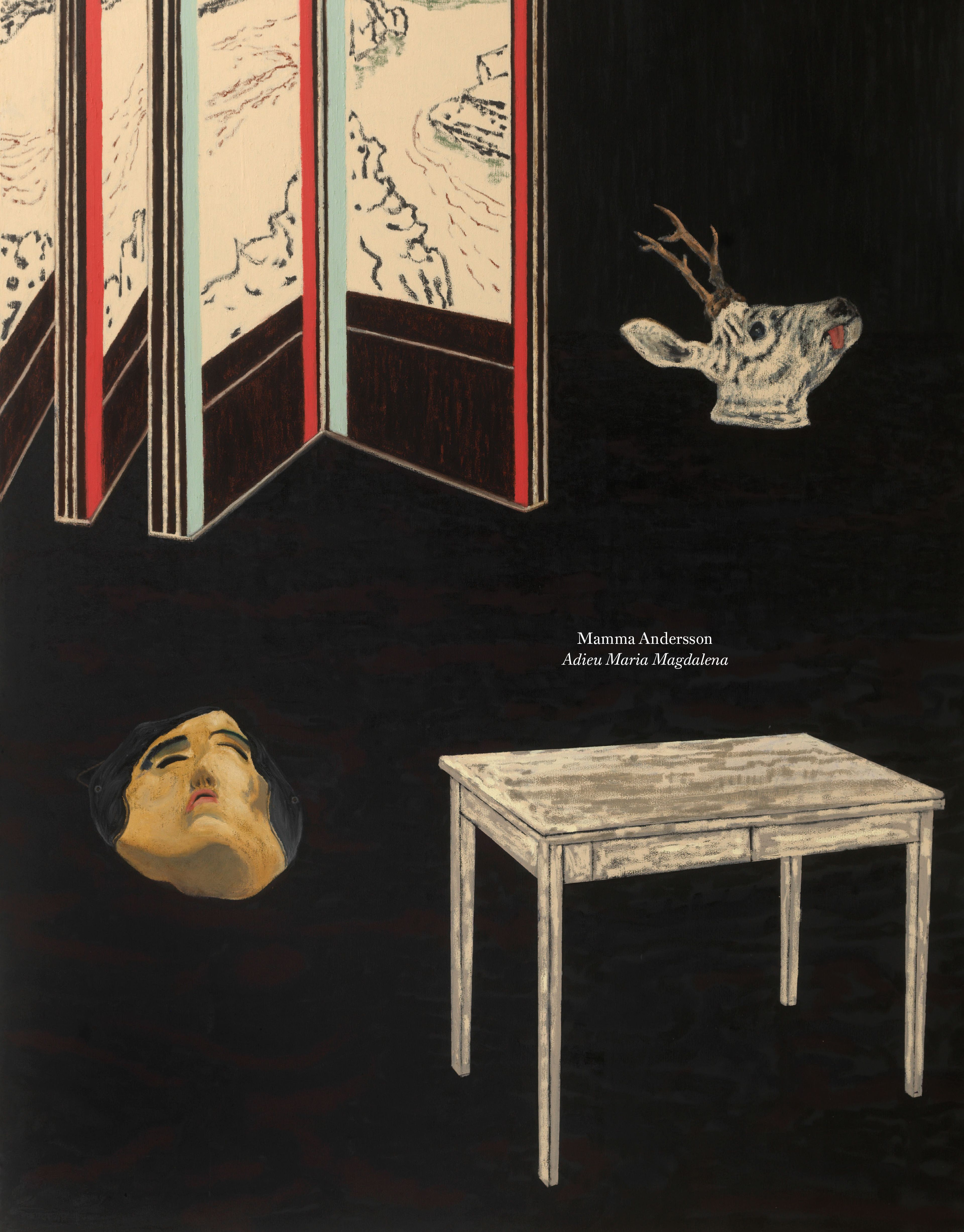

Mamma Andersson

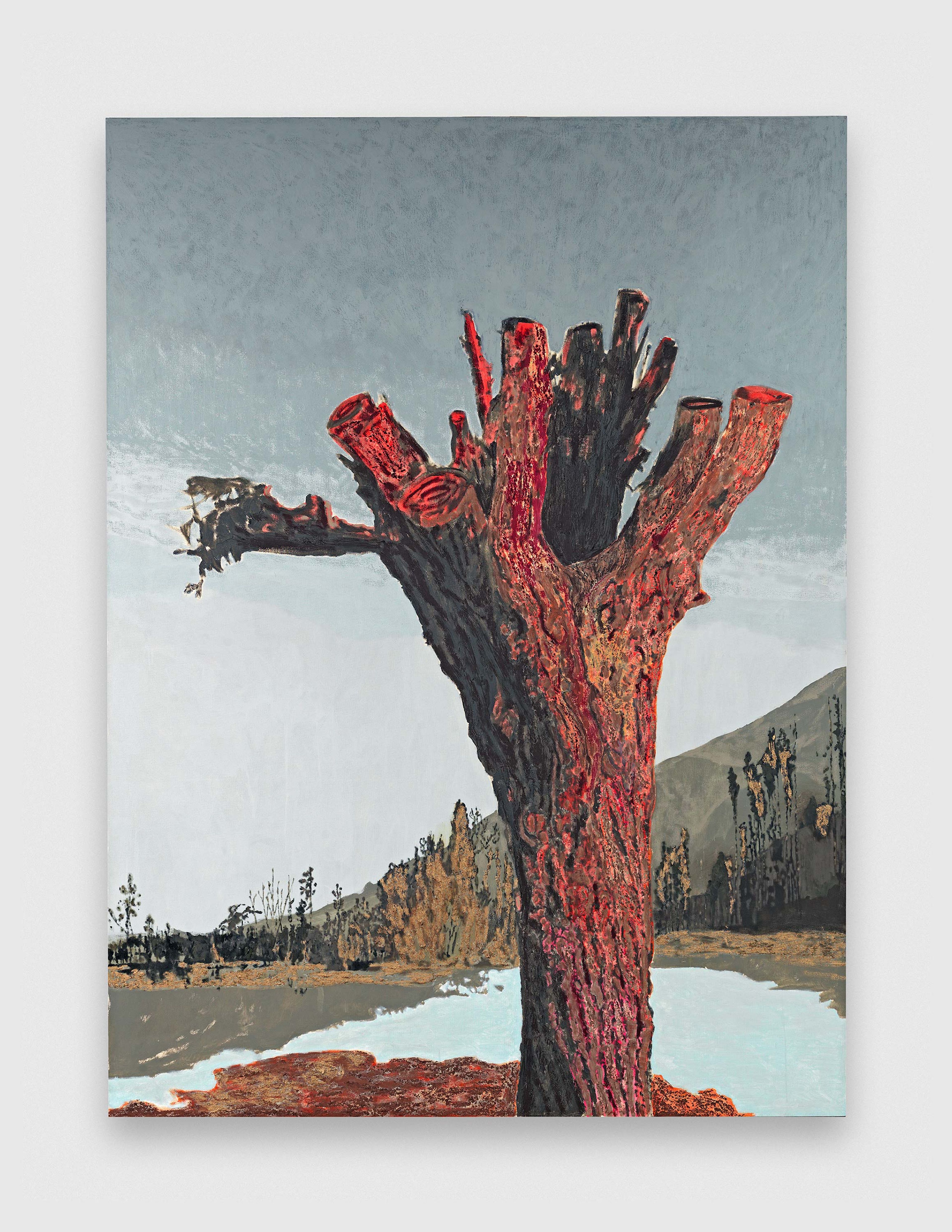

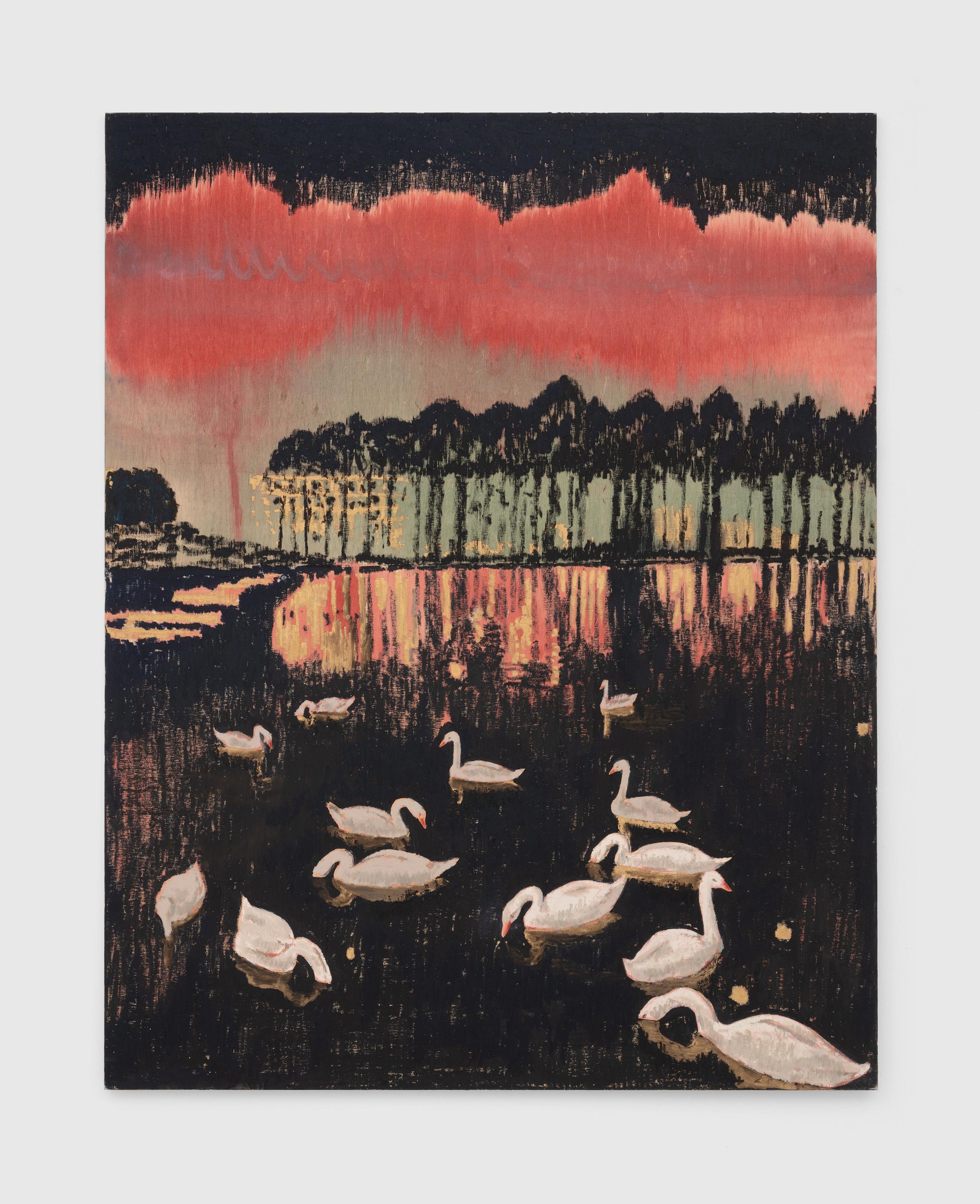

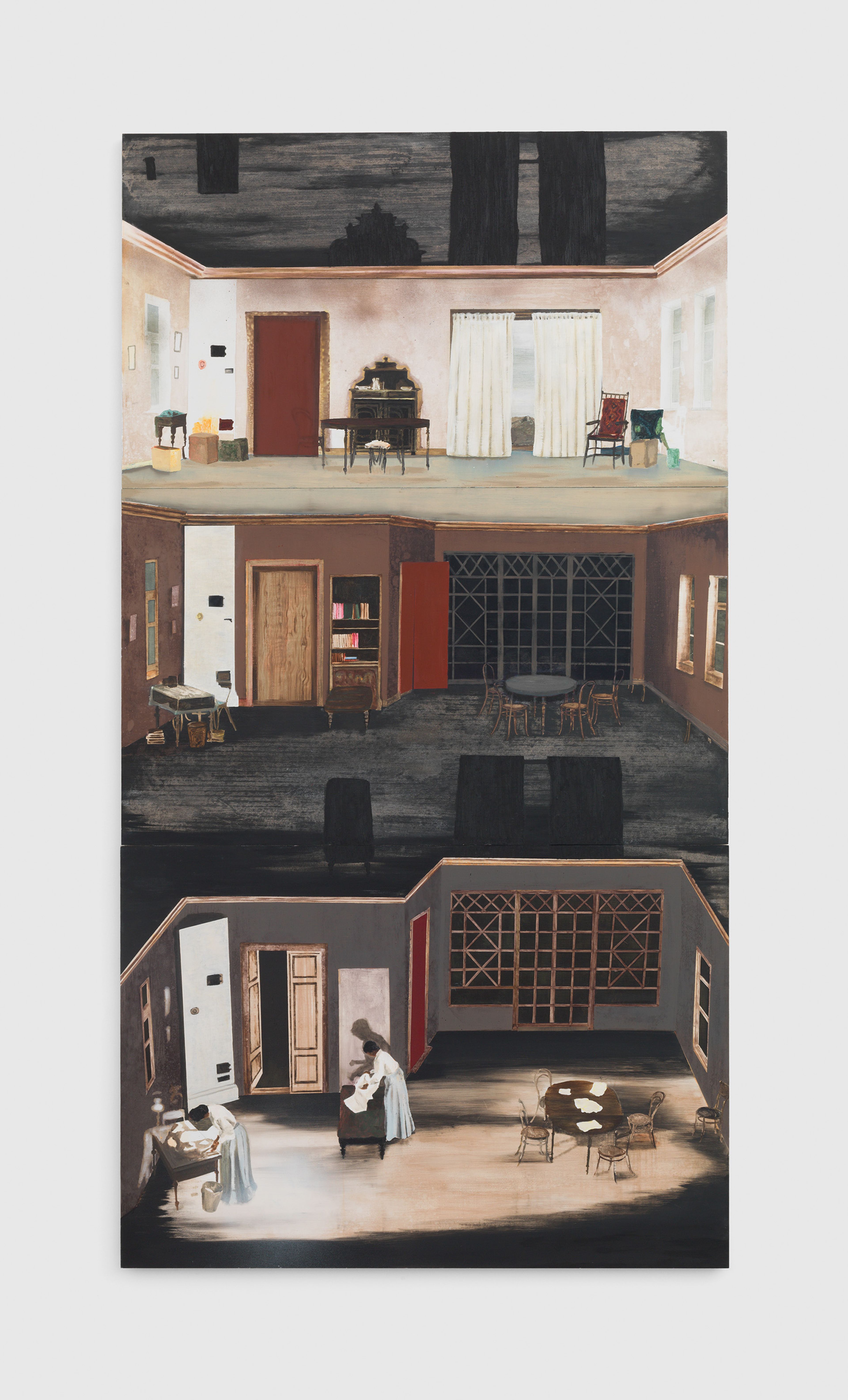

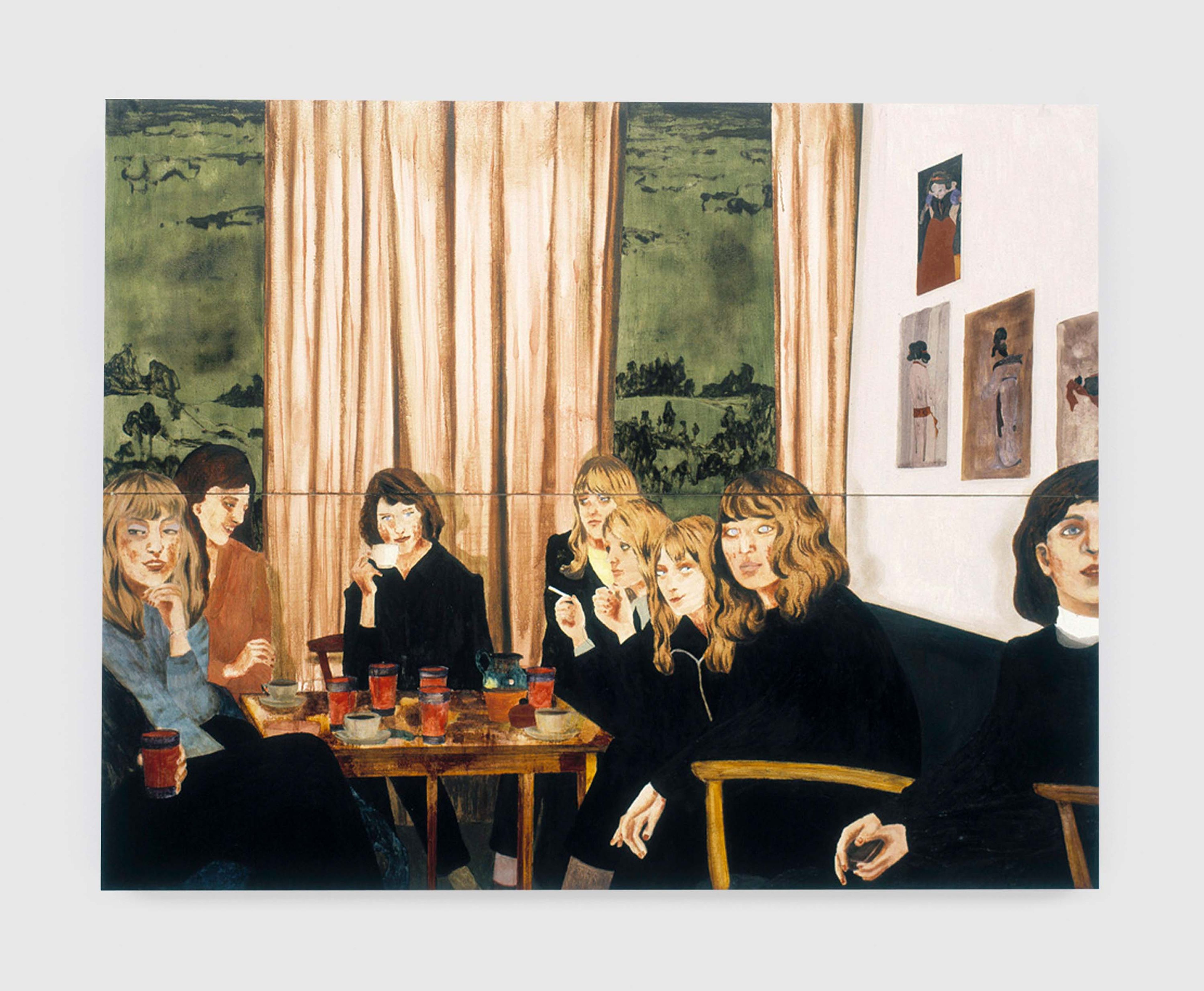

Characterized by a unique combination of textured brushstrokes, loose washes, stark graphic lines, and evocative colors, Mamma Andersson’s (b. 1962) works embody a new genre of painting that recalls late nineteenth-century romanticism while also embracing a contemporary interest in layered, psychological compositions that draw inspiration from a wide range of source materials.

Learn MoreSurvey

Available Artworks

Exhibitions

Explore Exhibitions

Artist News

Biography

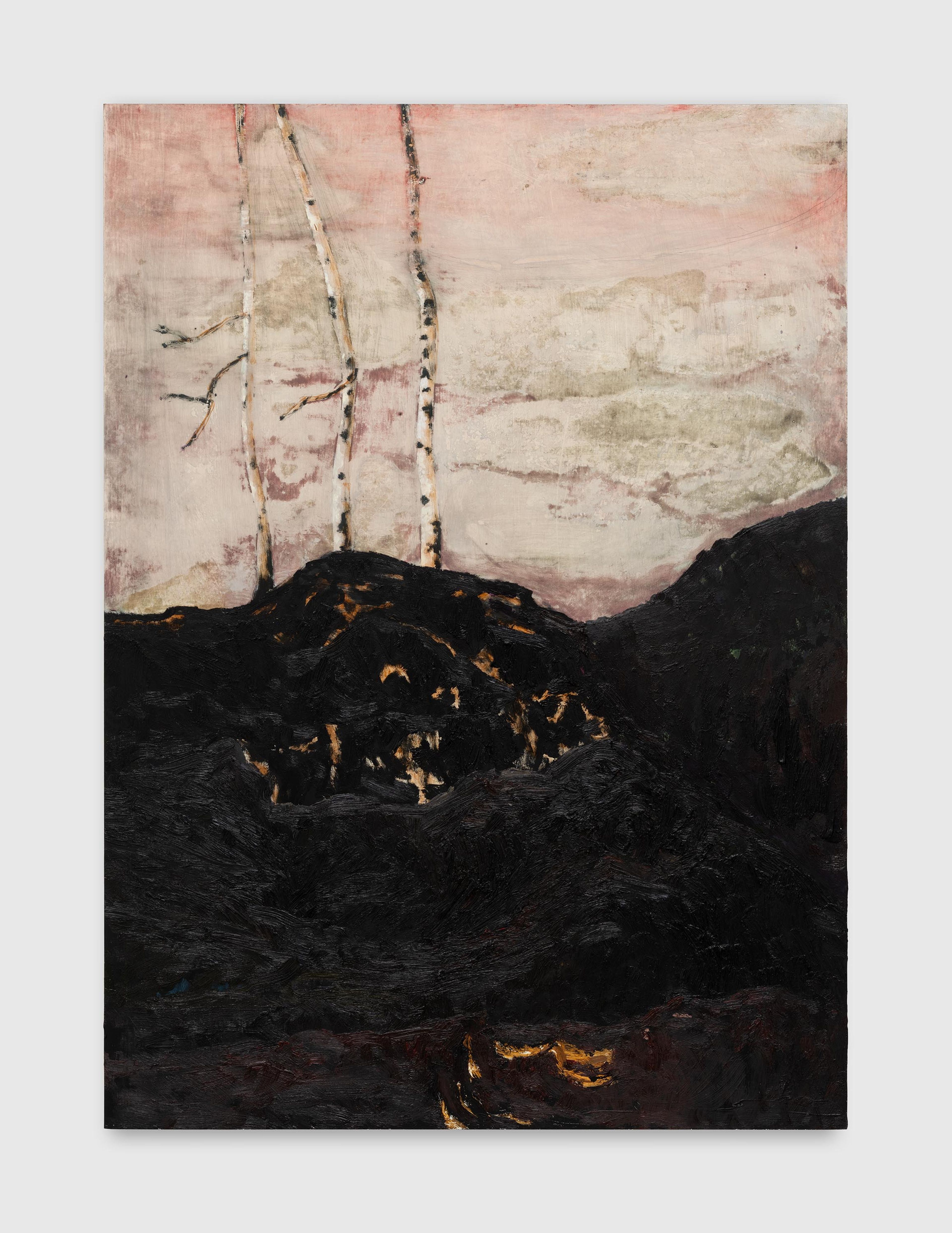

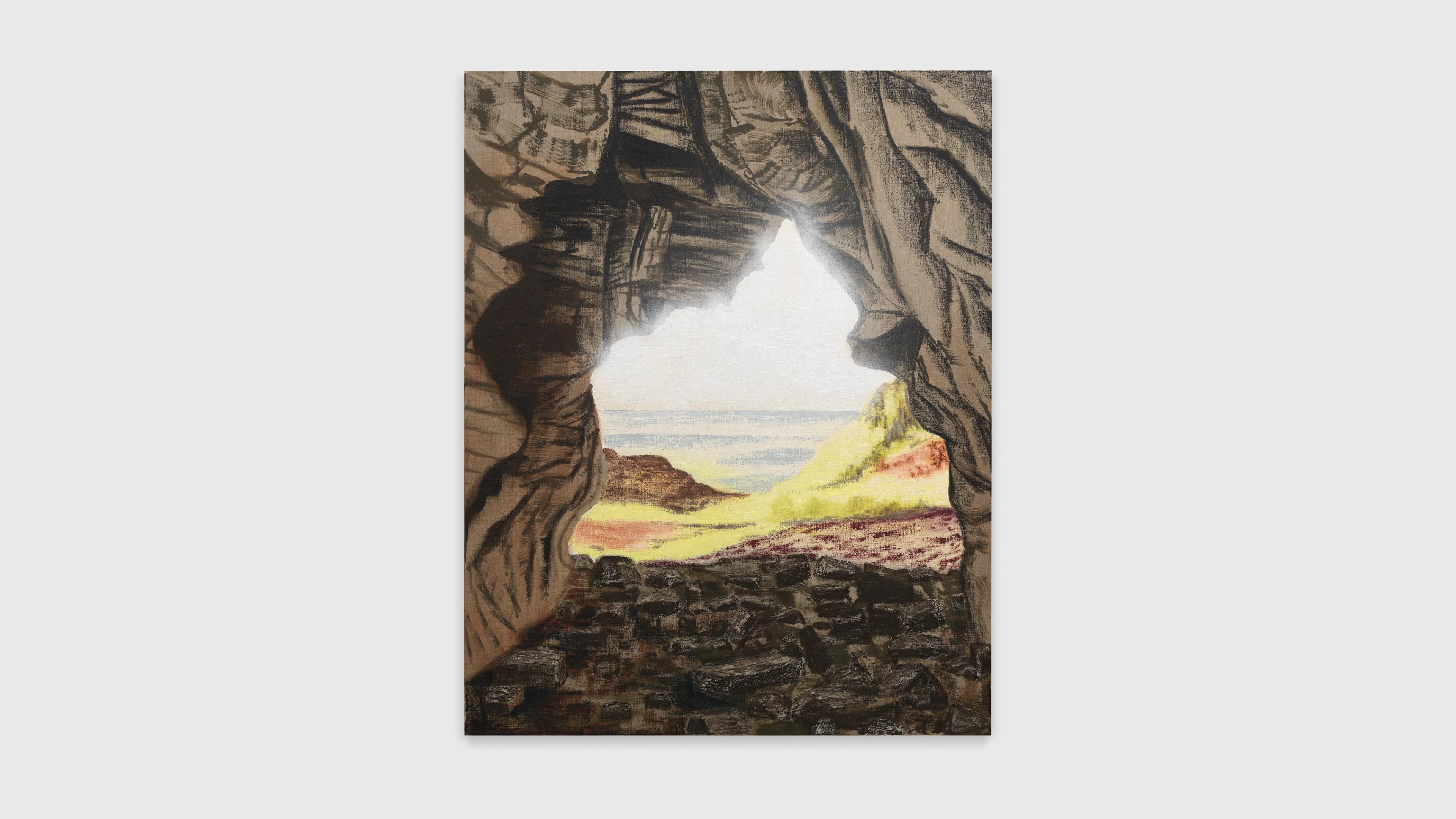

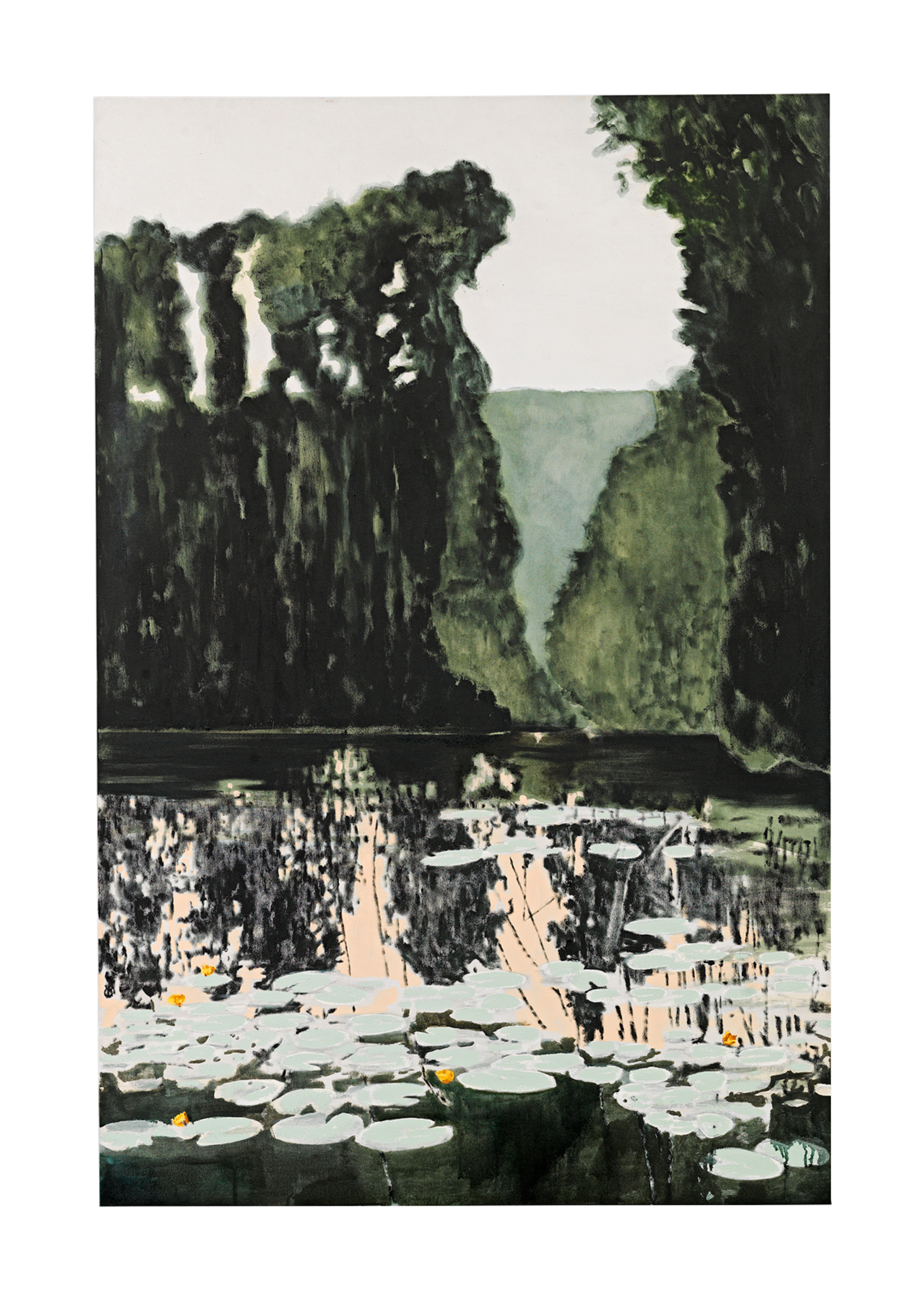

Mamma Andersson, Pond, 2019

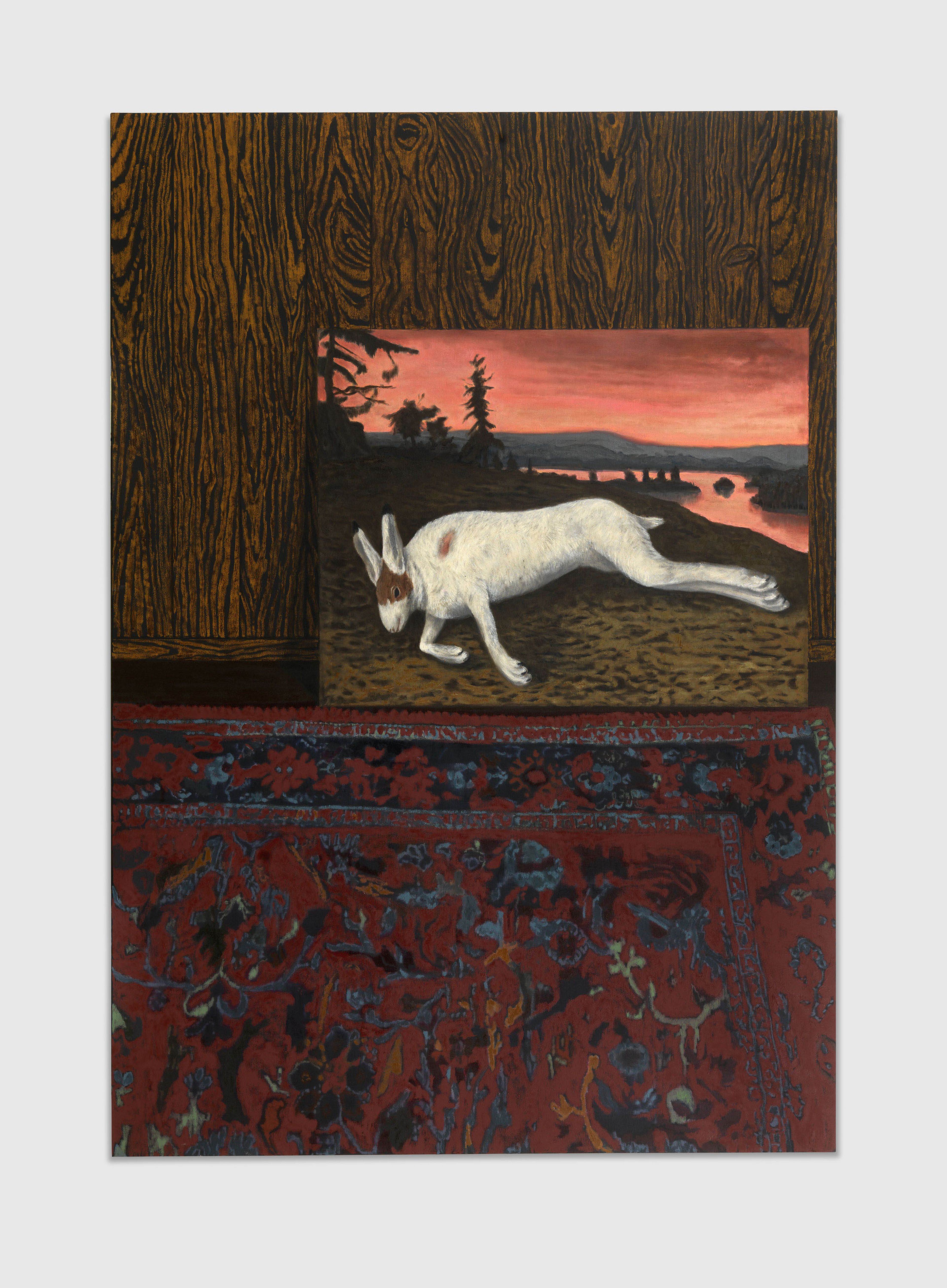

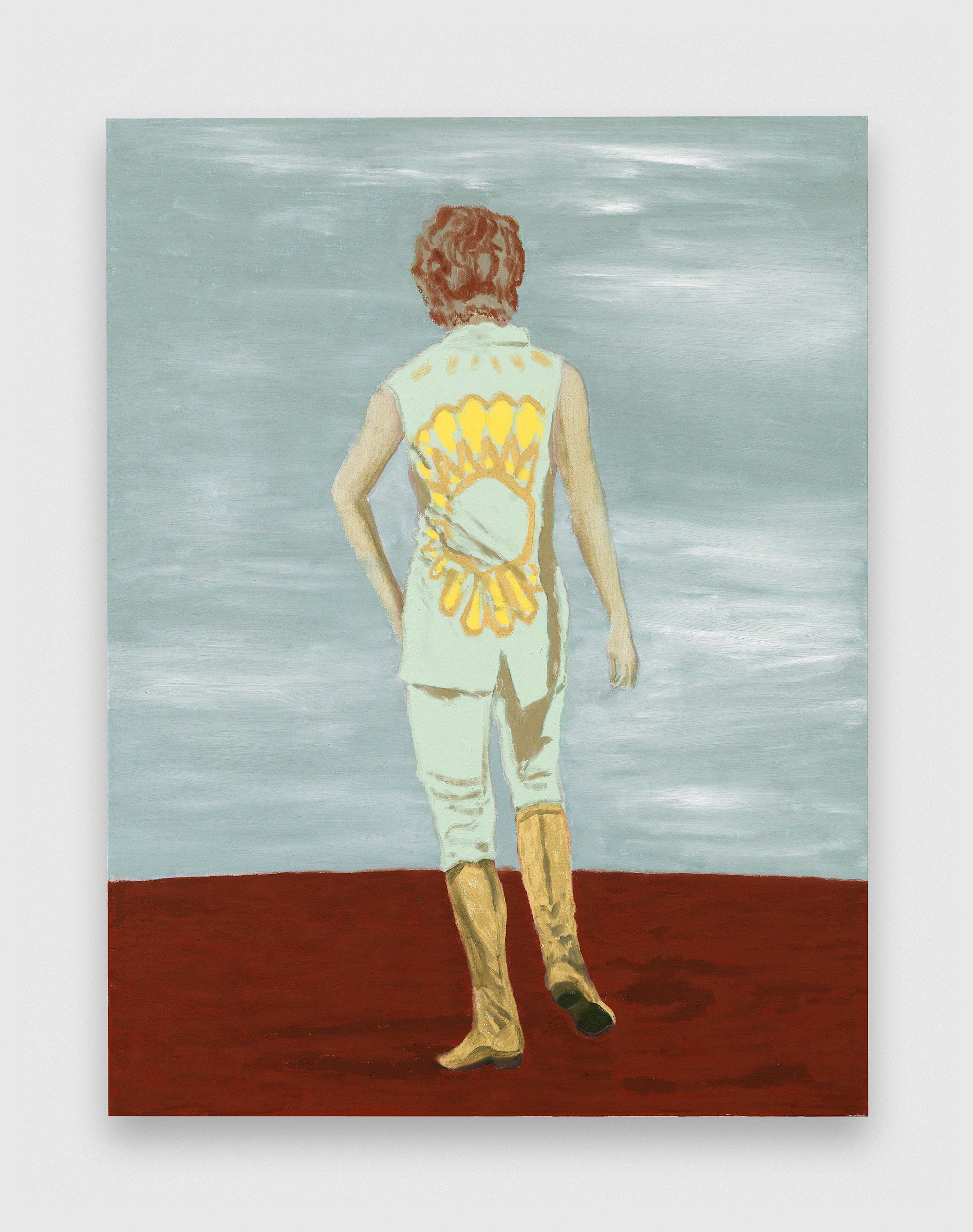

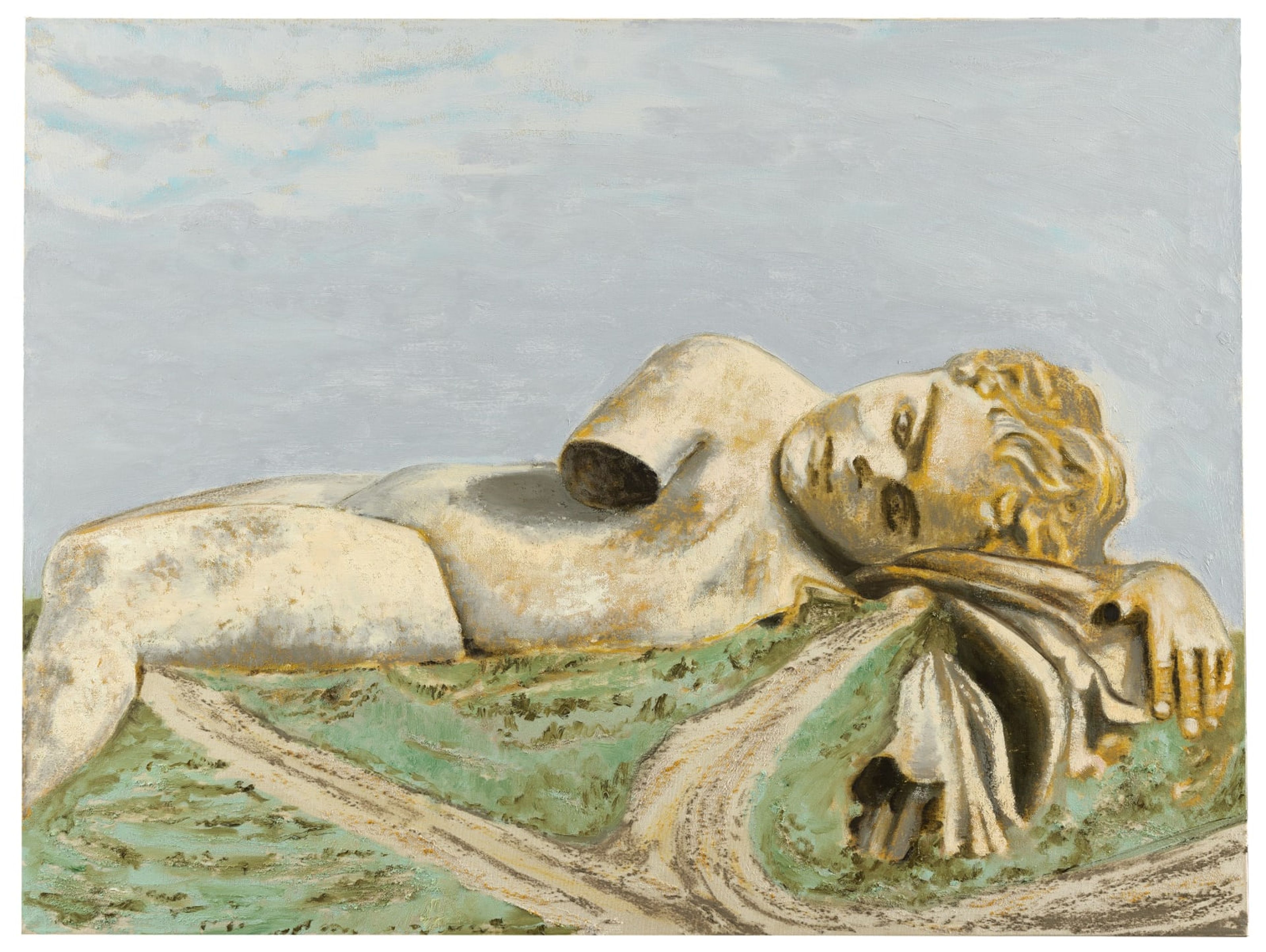

Characterized by a unique combination of textured brushstrokes, loose washes, stark graphic lines, and evocative colors, Mamma Andersson’s (b. 1962) works embody a new genre of painting that recalls late nineteenth-century romanticism while also embracing a contemporary interest in layered, psychological compositions. Her often-panoramic scenes draw inspiration from a wide range of archival photographic source materials, filmic imagery, theater sets, and period interiors, as well as the sparse topography of northern Sweden, where she grew up: mountainous backdrops, trees, snow, and wooden cabins are recurrent elements within her works. Yet, rather than conveying specific spatial or temporal reference points, they revolve around the expression of atmospheres and subjective moods, and frequently appear to merge the past, the present, and the future.

Andersson was born in Luleå, Sweden. She studied from 1986 to 1993 at the Kungl Konsthögskolan in Stockholm, where she continues to live and work.

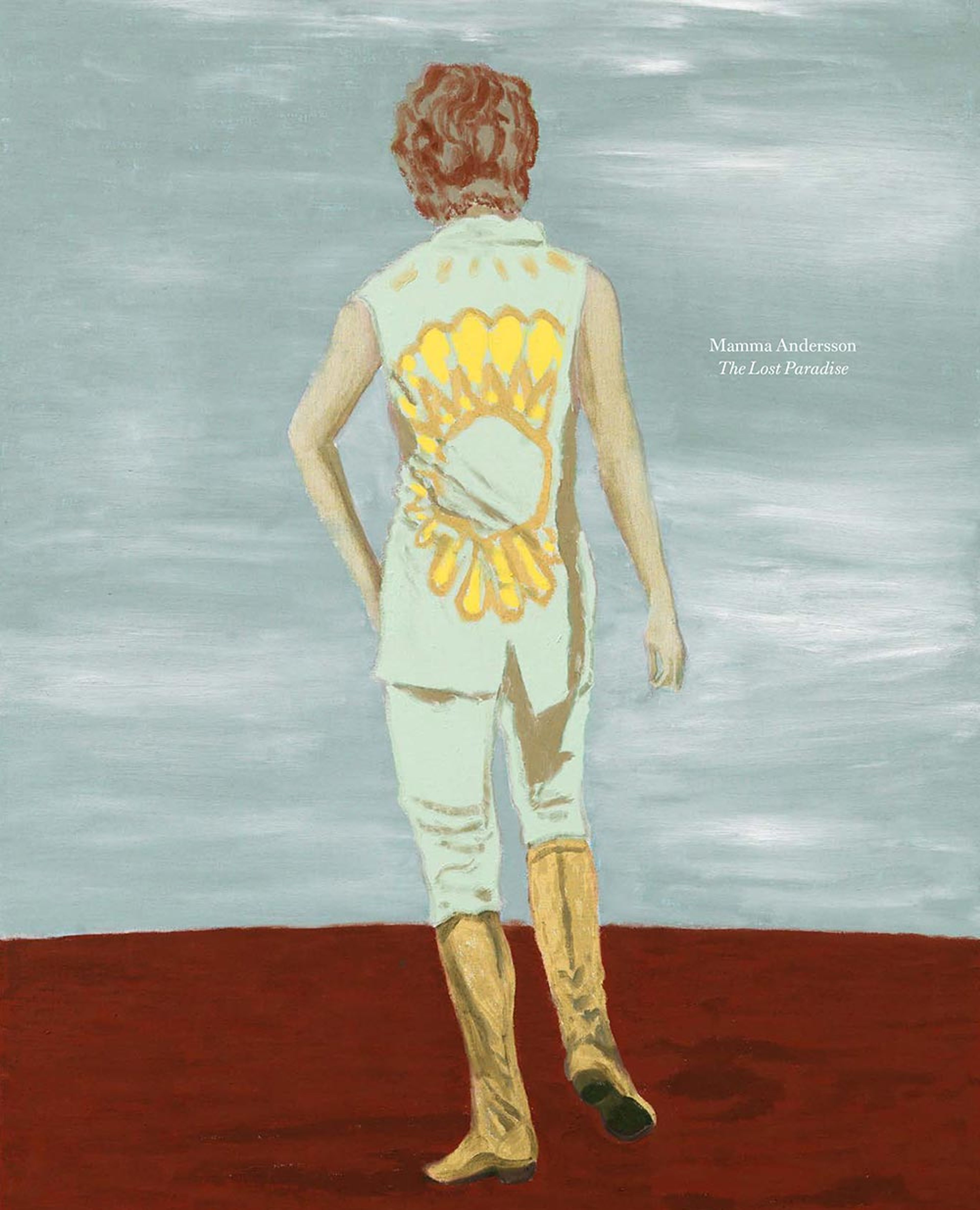

Andersson's work has been represented by David Zwirner since 2004. In October 2023, a solo presentation of the artist’s work titled Adieu Maria Magdalena opened at David Zwirner, Paris, marking the artist’s fifth solo exhibition with the gallery. The Lost Paradise was on view at David Zwirner, New York, in 2020. The artist’s previous shows with the gallery include Behind the Curtain (2015); Who is sleeping on my pillow (2010), a two-person exhibition with Jockum Nordström; and Rooms Under the Influence (2006), which marked the artist's United States debut.

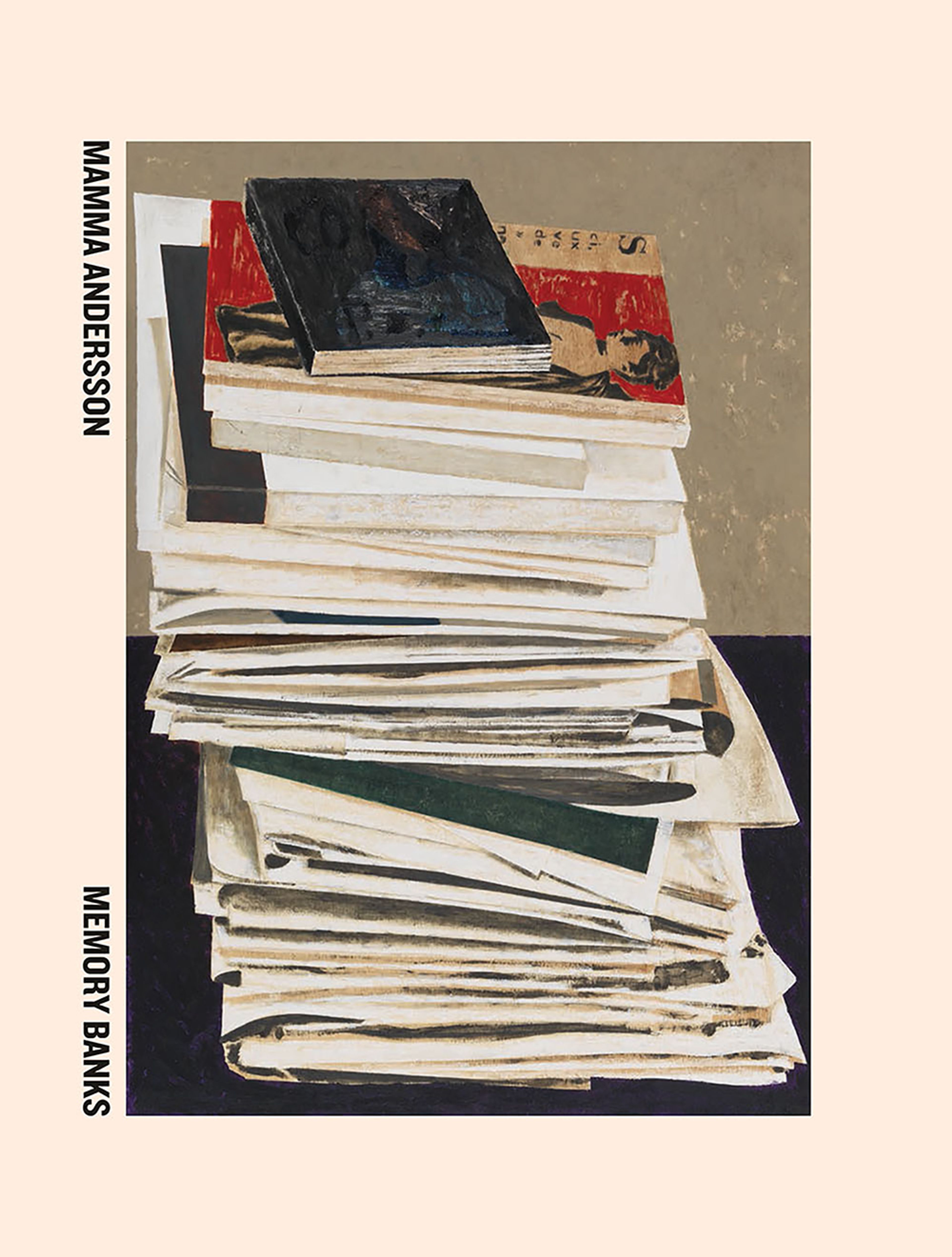

Mamma Andersson: A history over and over again, the artist's first solo exhibition in Asia, was presented in 2025 at the He Art Museum in Foshan, China. In 2022, the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, Denmark, organized the two-person presentation Tal R & Mamma Andersson–About Hill, which traveled to Malmö Konstmuseum, Sweden, and Museum MORE, Gorssel, the Netherlands (2023). In 2021, the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, presented a solo exhibition of the artist’s work, Mamma Andersson: Humdrum Days. In 2018, a solo presentation of Andersson’s work titled Memory Banks was on view at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 2011, the artist’s work was the subject of a solo exhibition at Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld, Germany. She had her first solo museum show in the United States at the Aspen Art Museum, Colorado, in 2010, and her first solo exhibition in Ireland at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, in 2009. In 2007, a critically acclaimed mid-career survey of her work was organized by the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, which traveled to Kunsthalle Helsinki and the Camden Arts Centre, London.

For the 33rd Bienal de São Paulo in 2018, Andersson curated the group presentation Stargazer II, which featured a number of the artist’s paintings. In 2006, she won the Carnegie Art Award, a prestigious prize for Nordic contemporary painting, and received a corresponding exhibition that traveled extensively throughout Europe. Her work was also represented in the Nordic Pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale, Dreams and Conflicts – The Viewer’s Dictatorship, in 2003.

Work by the artist is represented in museum collections worldwide, including the Centre Pompidou, Paris; Dallas Museum of Art; Göteborgs Konstmuseum, Gothenburg, Sweden; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark; Magasin III, Stockholm; Malmö Konstmuseum, Sweden; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Public Art Council, Stockholm; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and the Västerås Konstmuseum, Sweden.

Selected Press

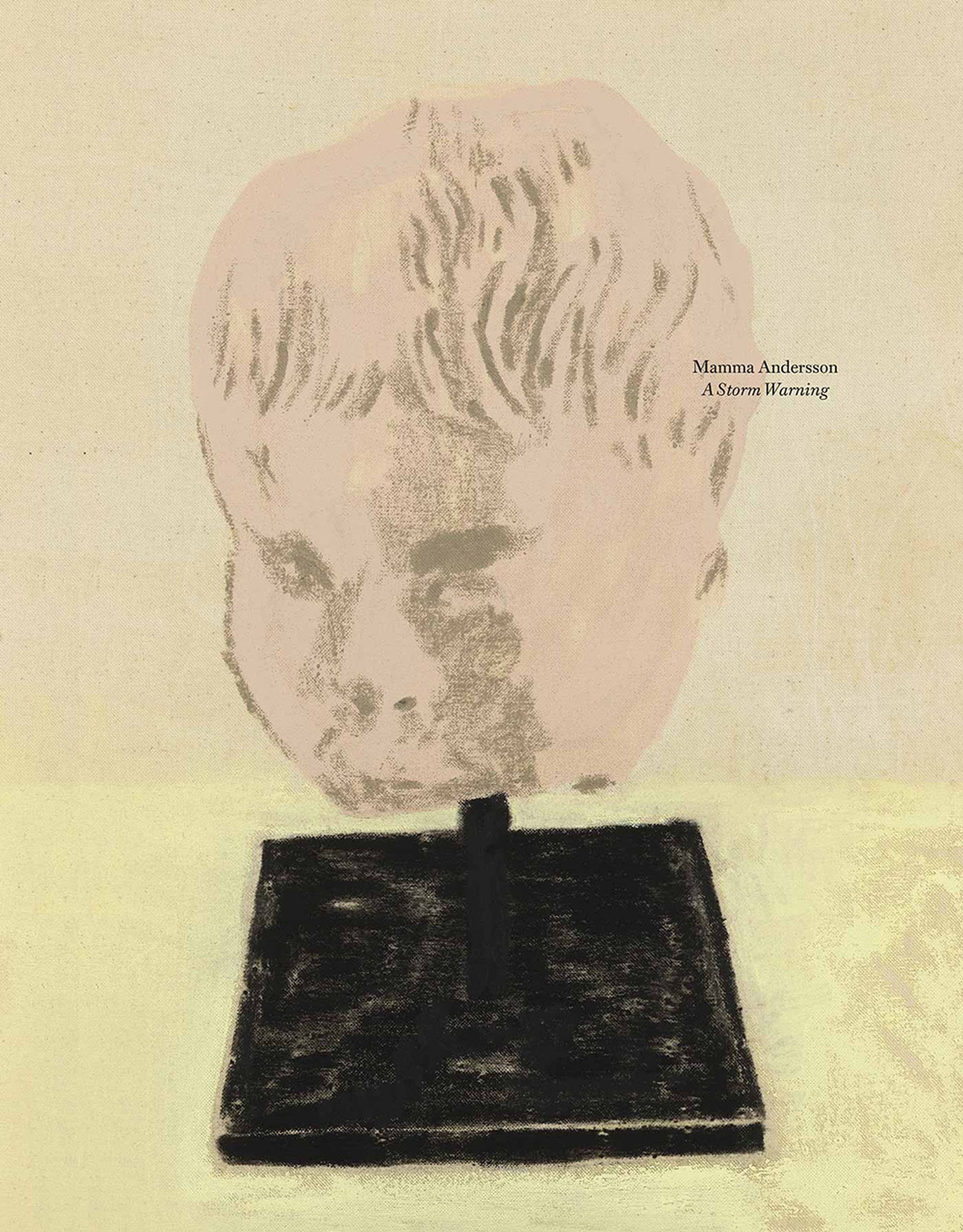

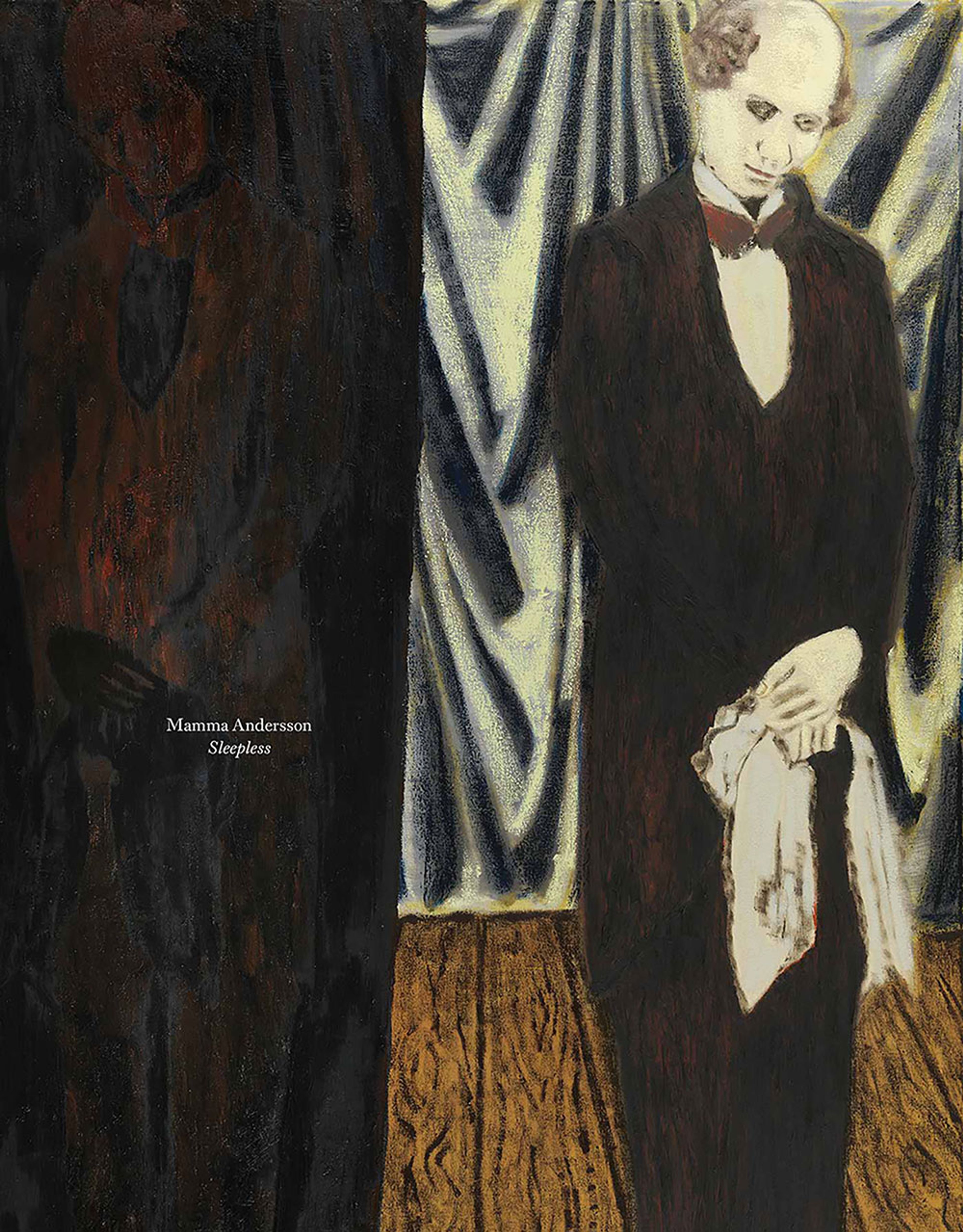

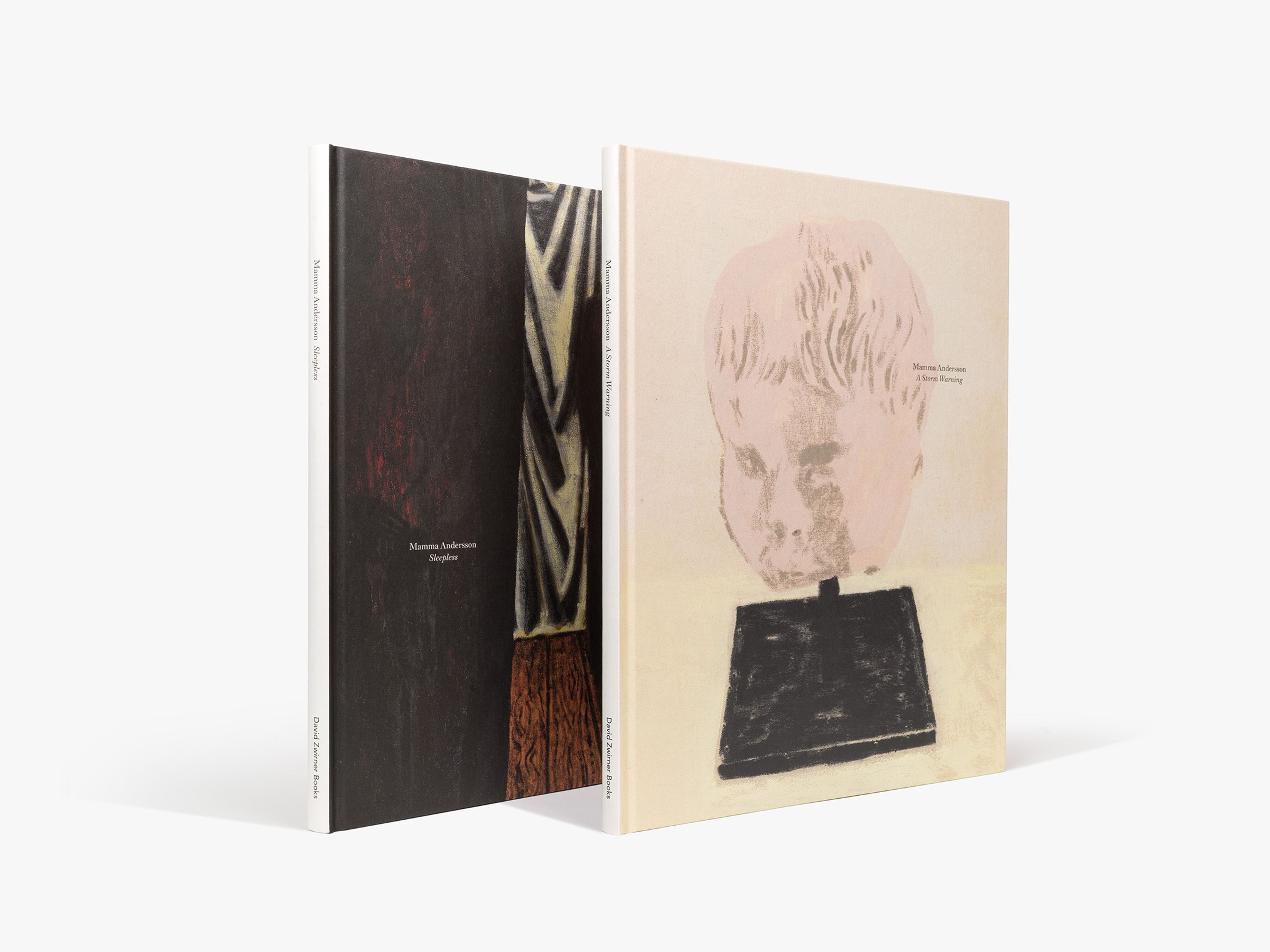

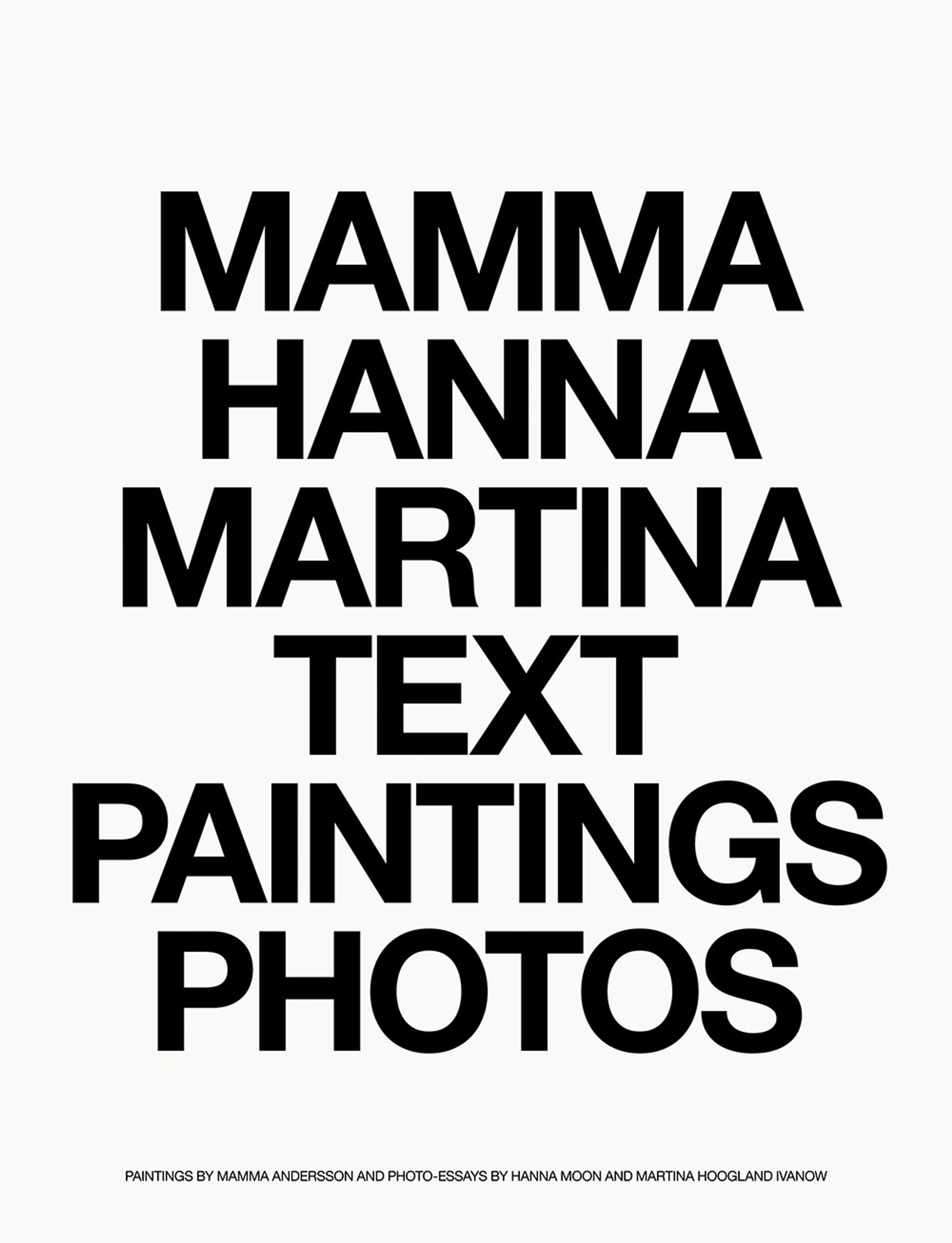

Selected Titles

Request more information