Paul Klee

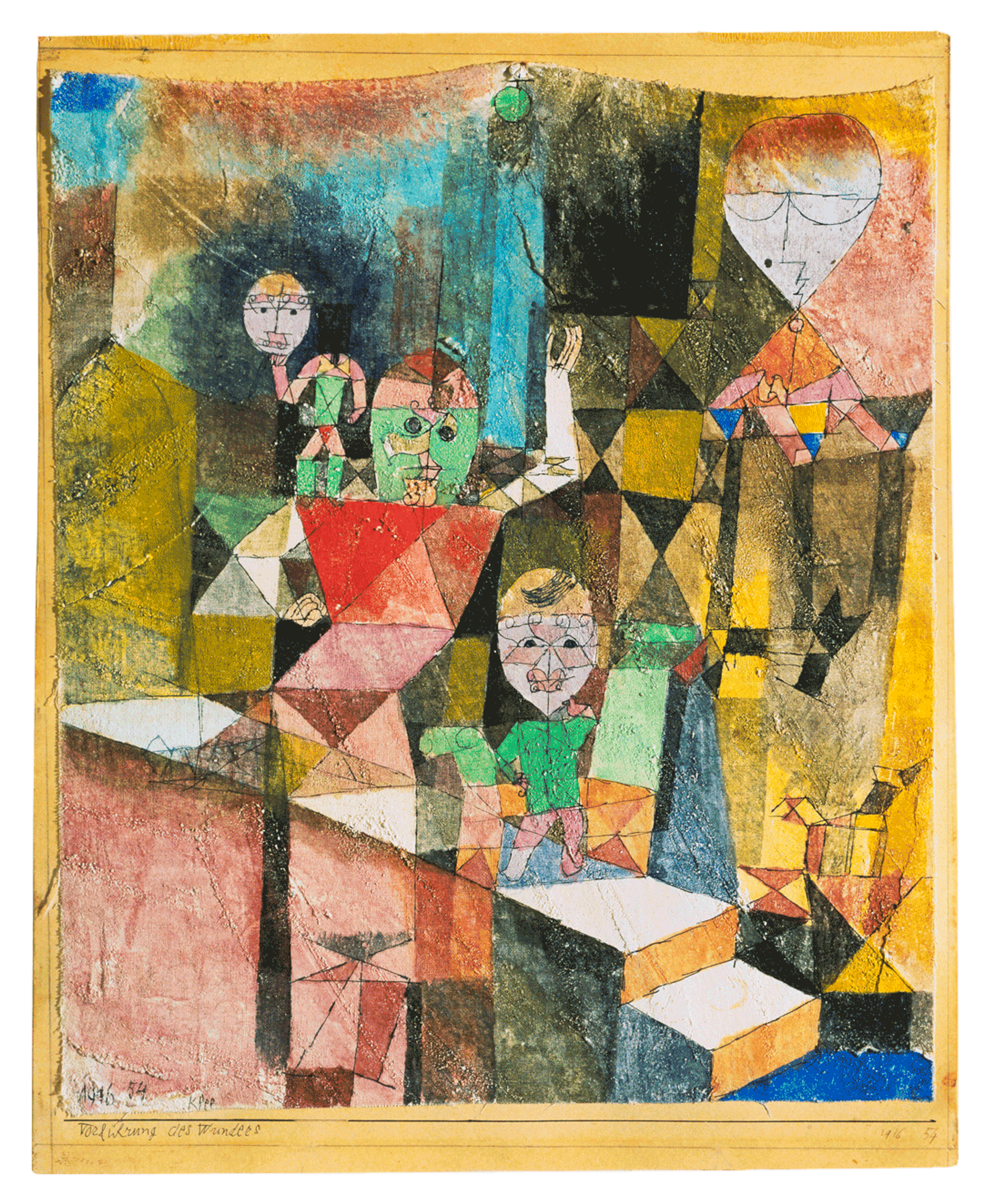

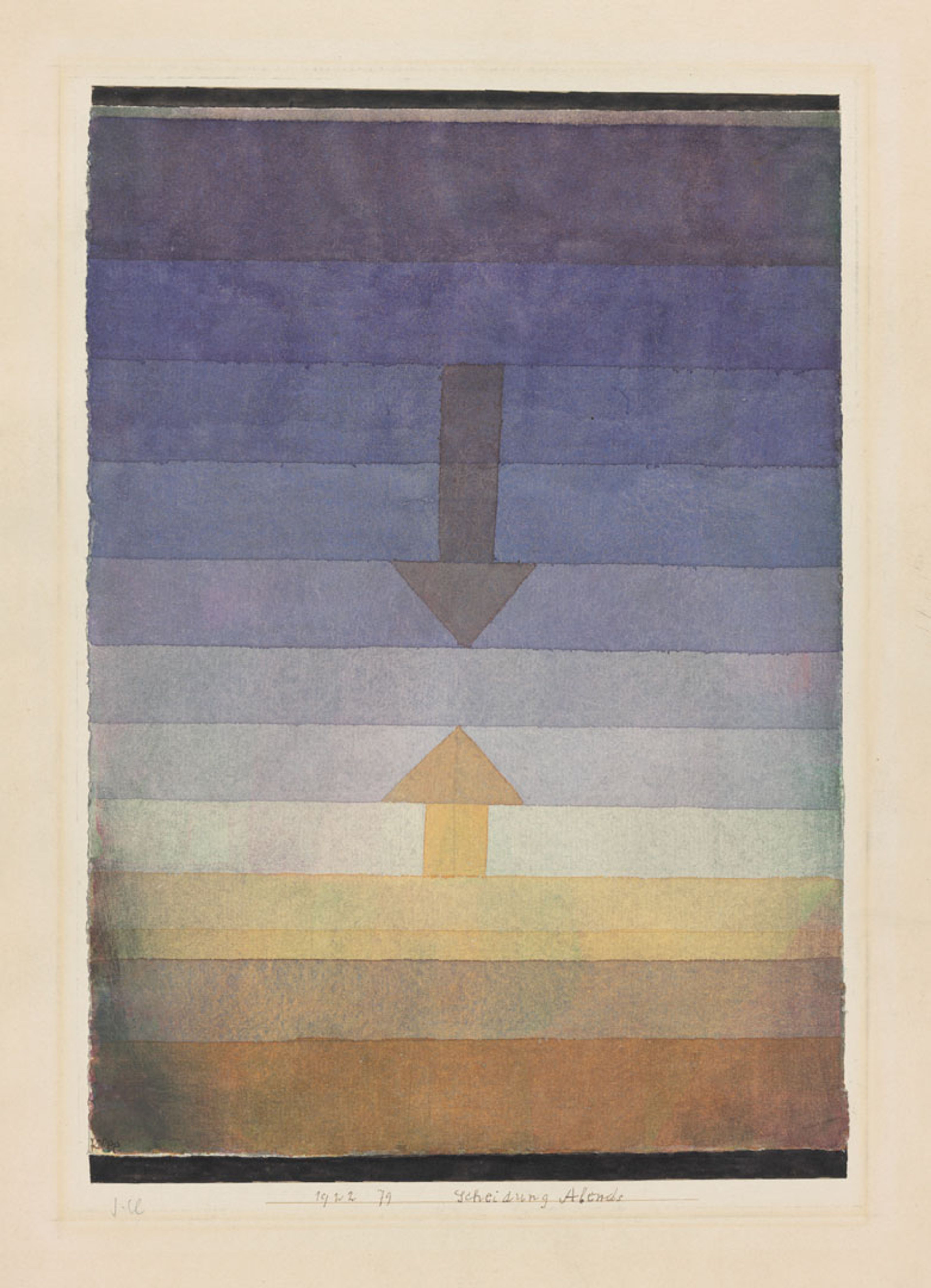

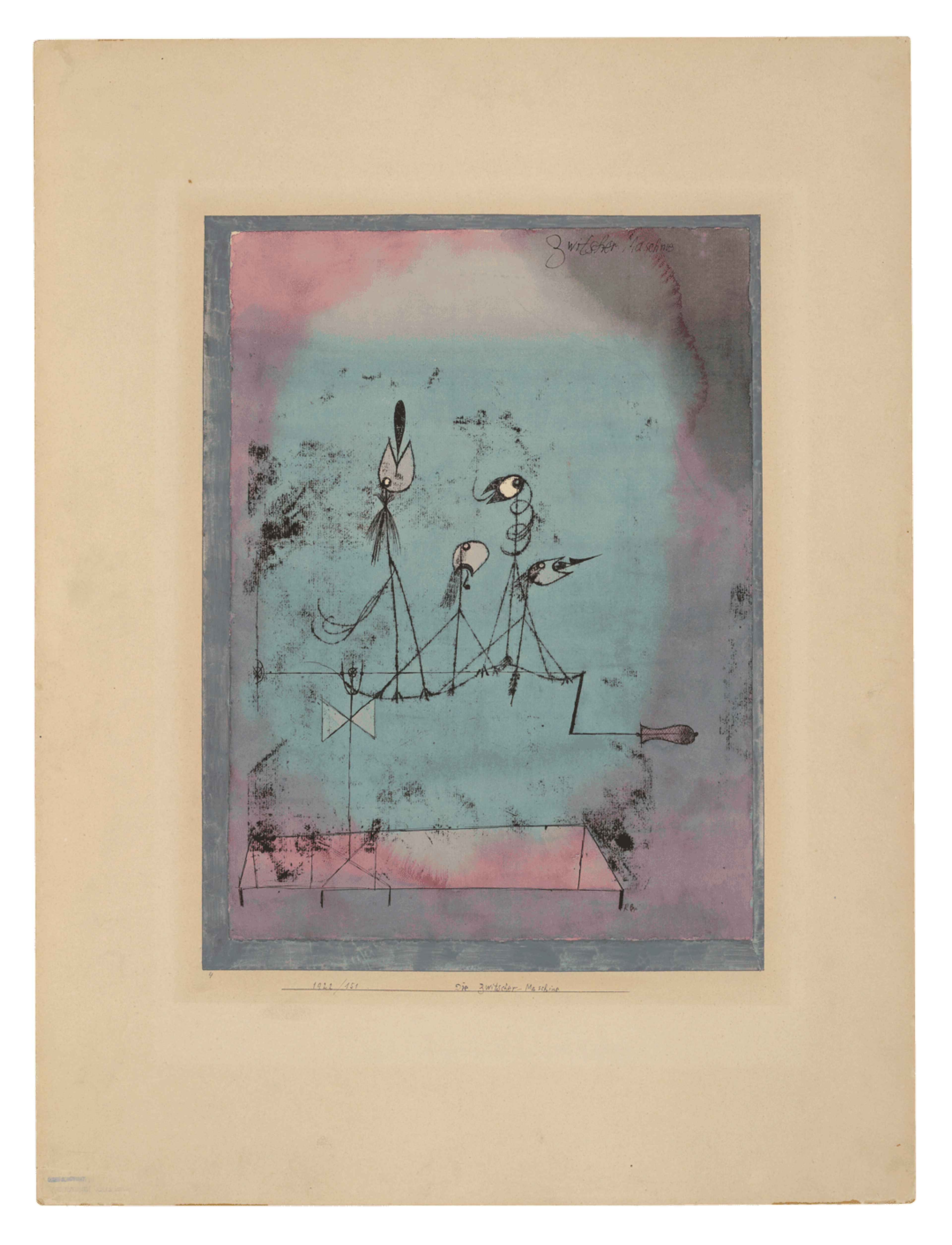

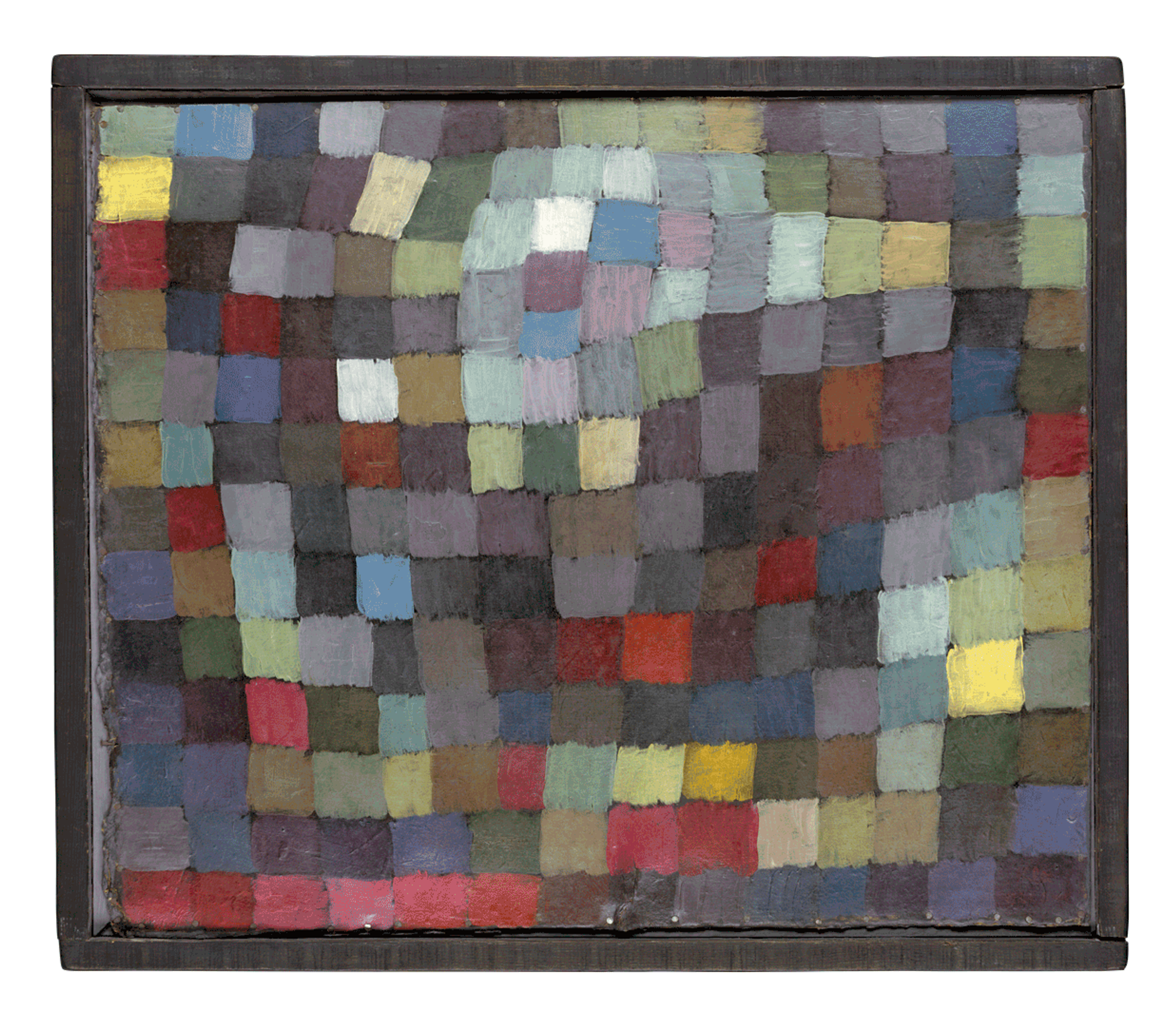

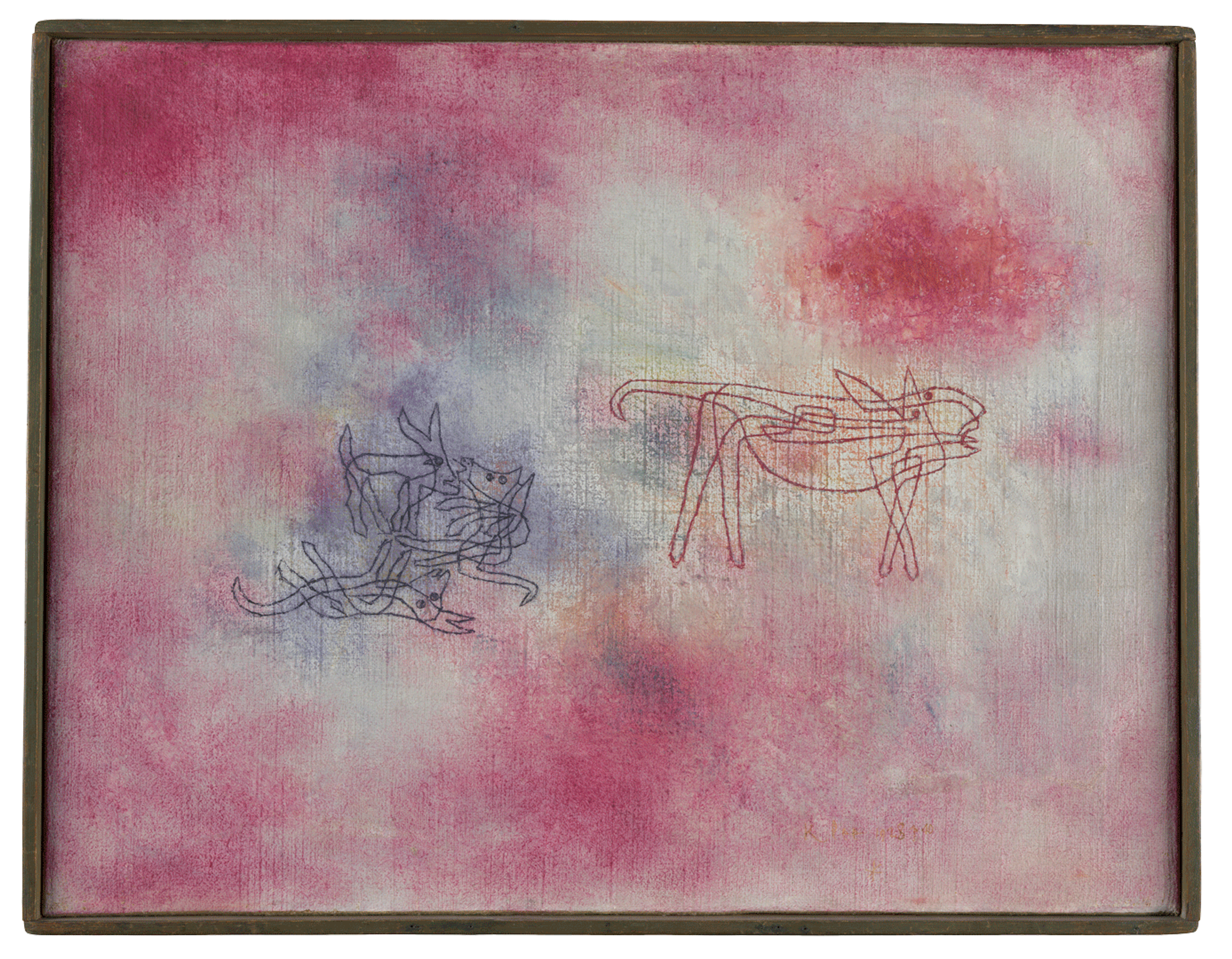

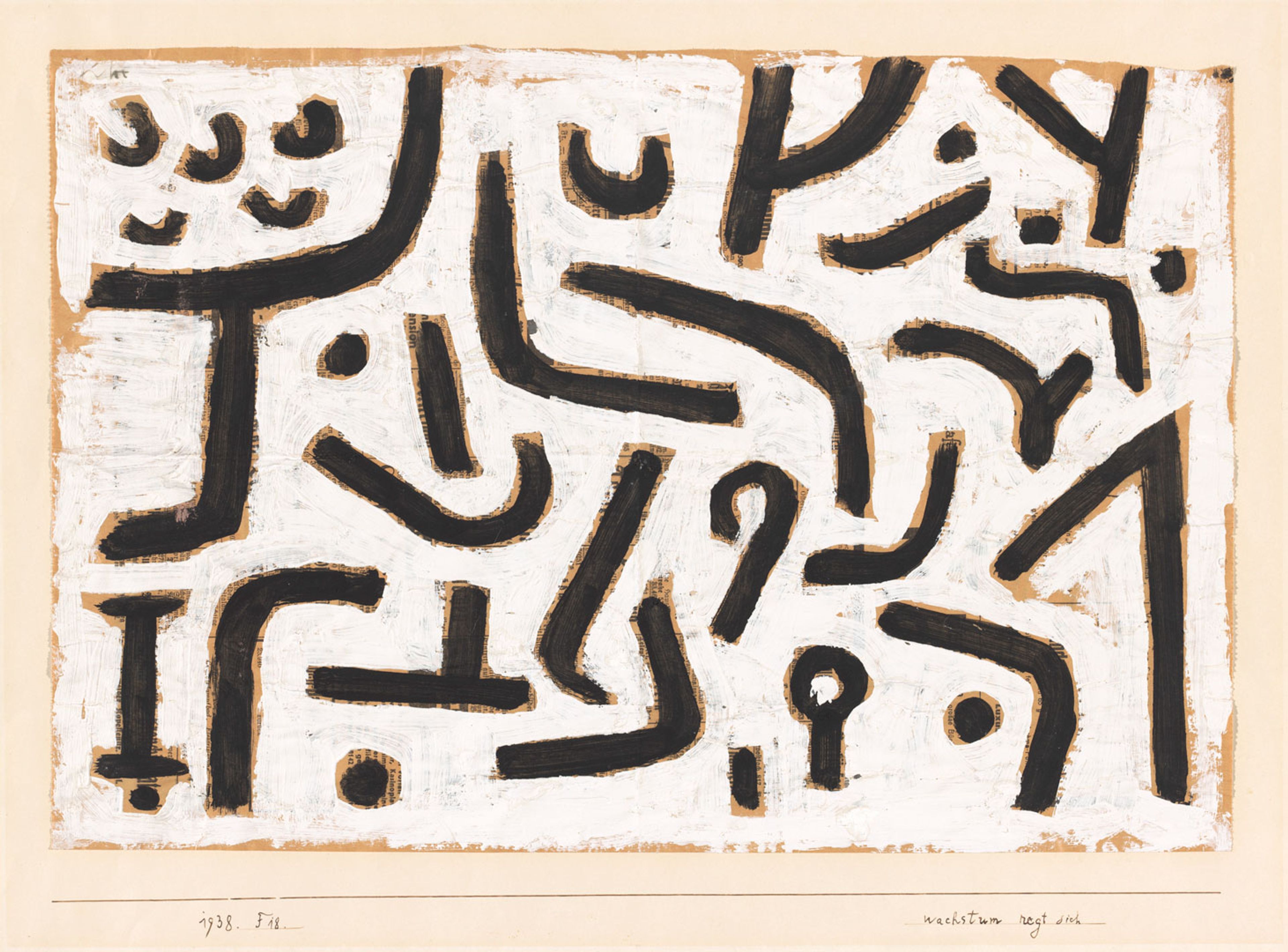

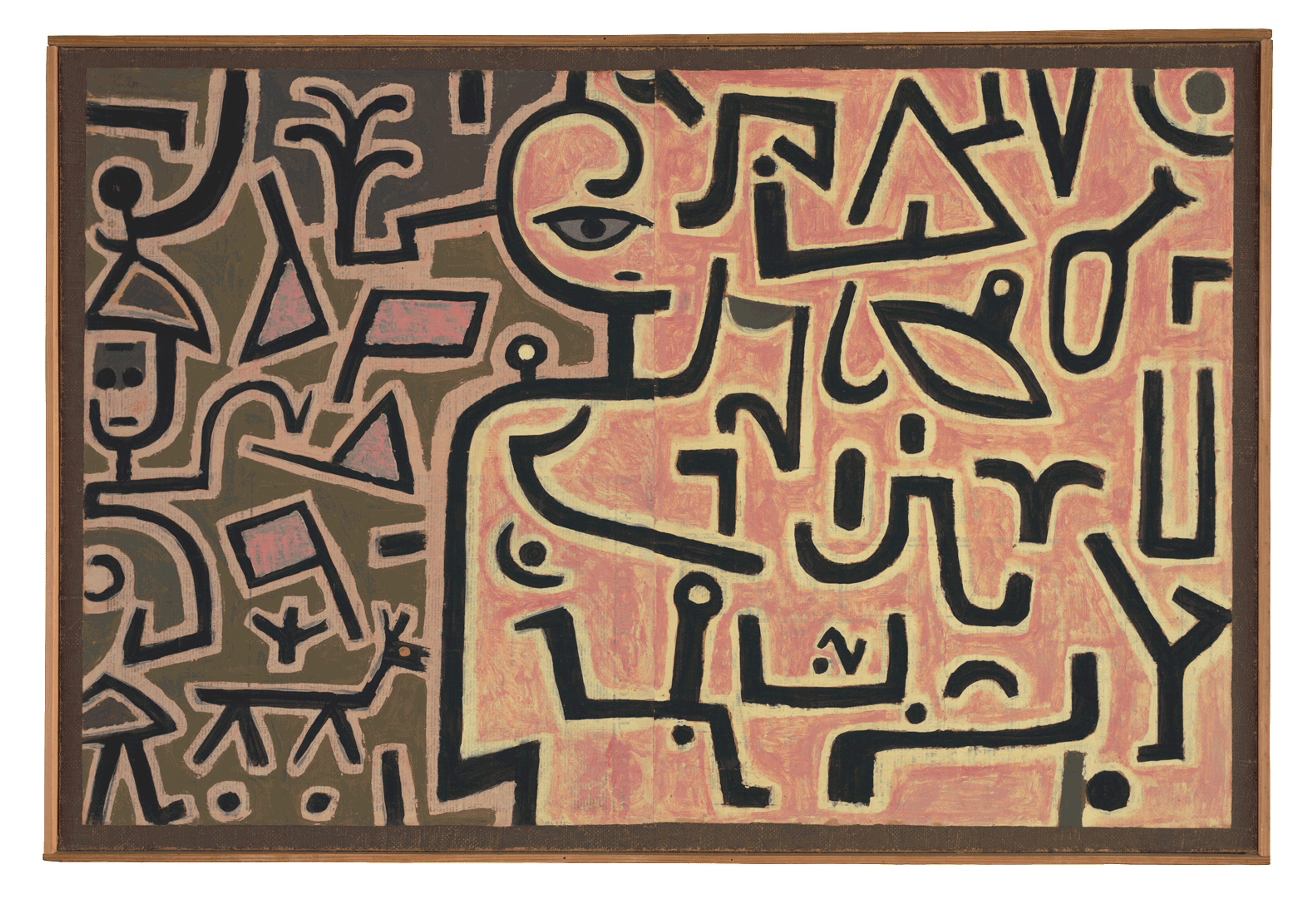

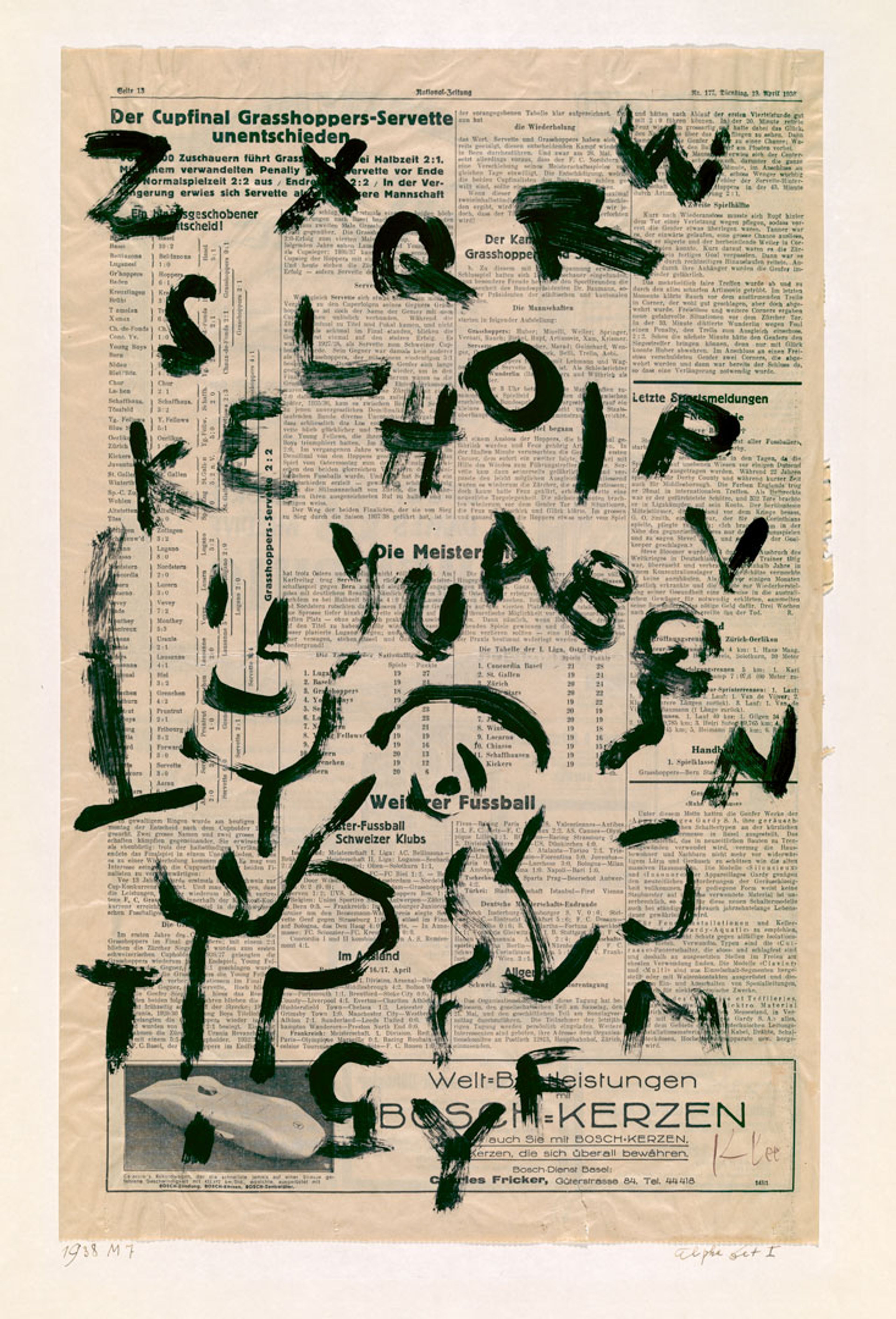

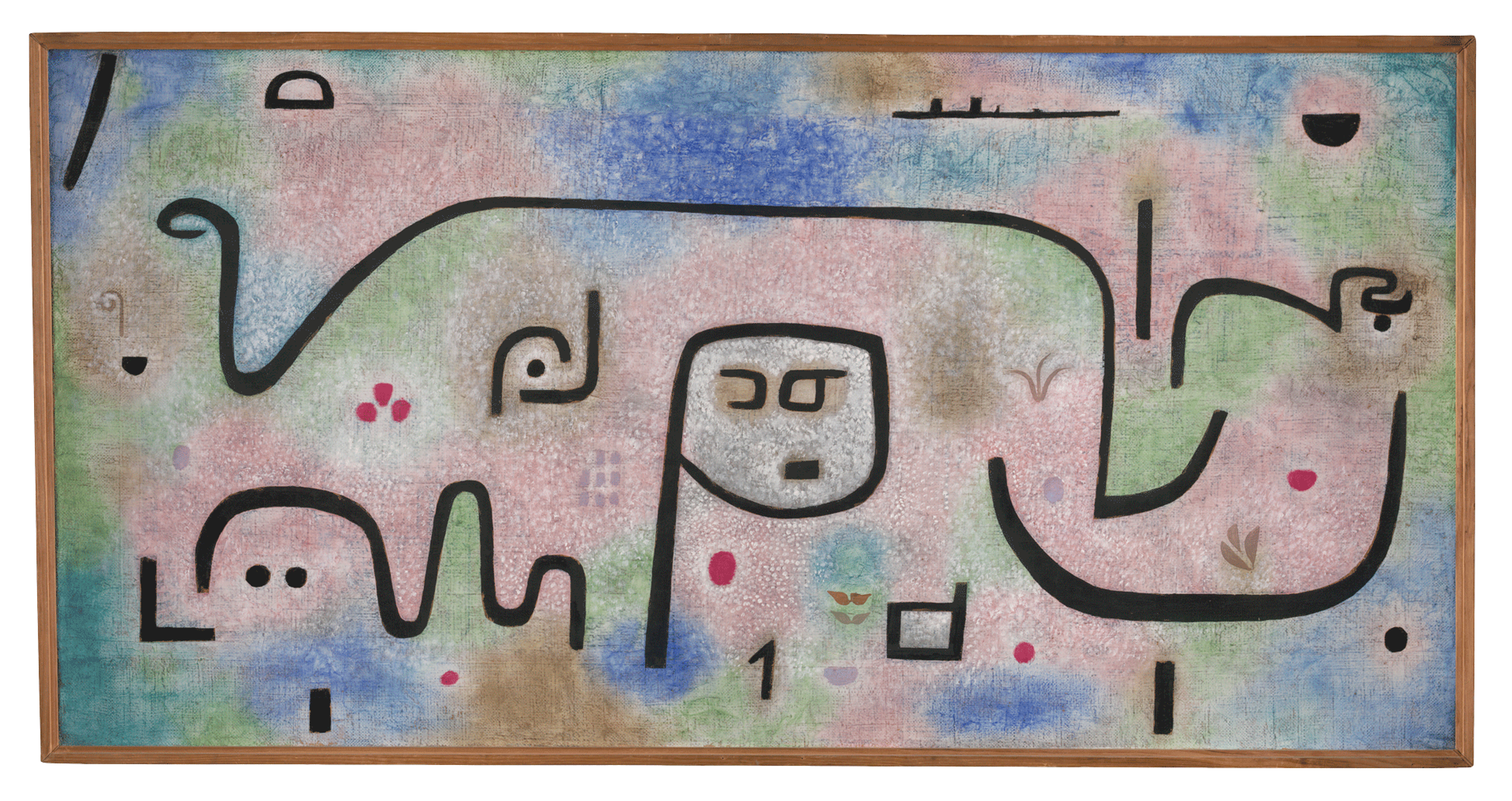

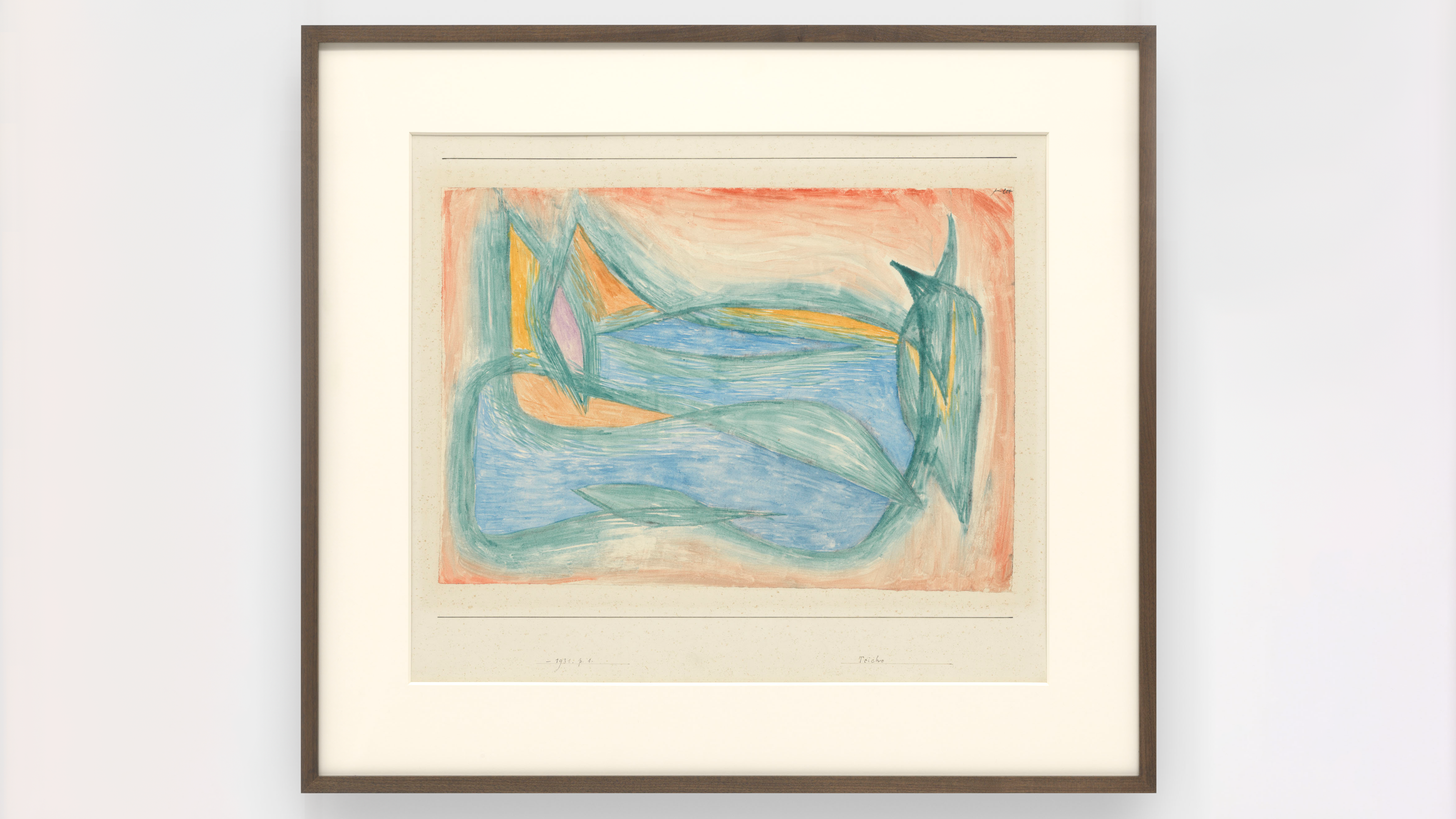

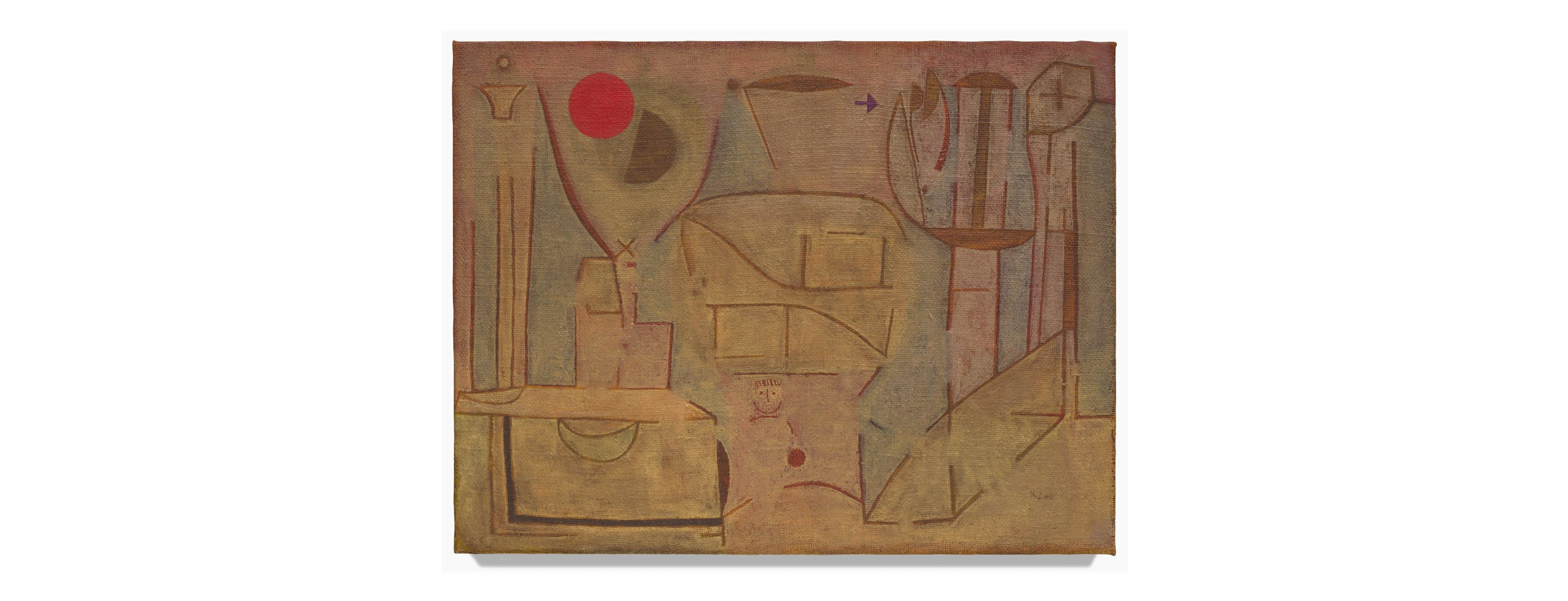

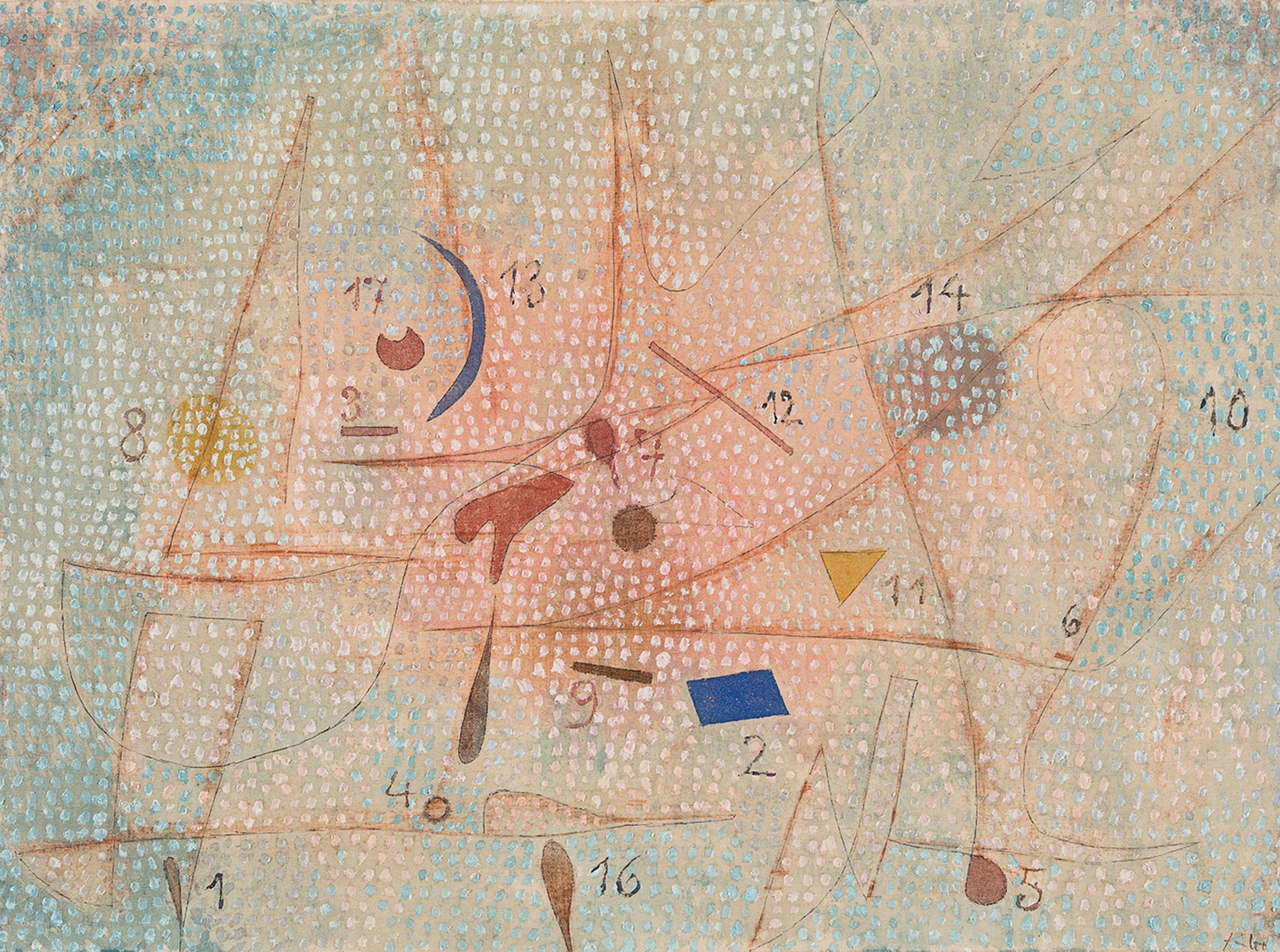

A pioneering modernist of unrivaled creative output, Paul Klee (1879–1940) counts among the truly defining artists of the twentieth century, exploring and expanding the terrain of avant-garde art through work that ranges from stunning colorist grids to evocative graphic productions. Klee taught for a decade, from 1921 to 1931, at the Bauhaus, the famed German art and design school, and the novelty of his work and ideas established him as one of the institution’s foremost instructors.

Learn MoreSurvey

Exhibitions

Explore Exhibitions

Artist News

Biography

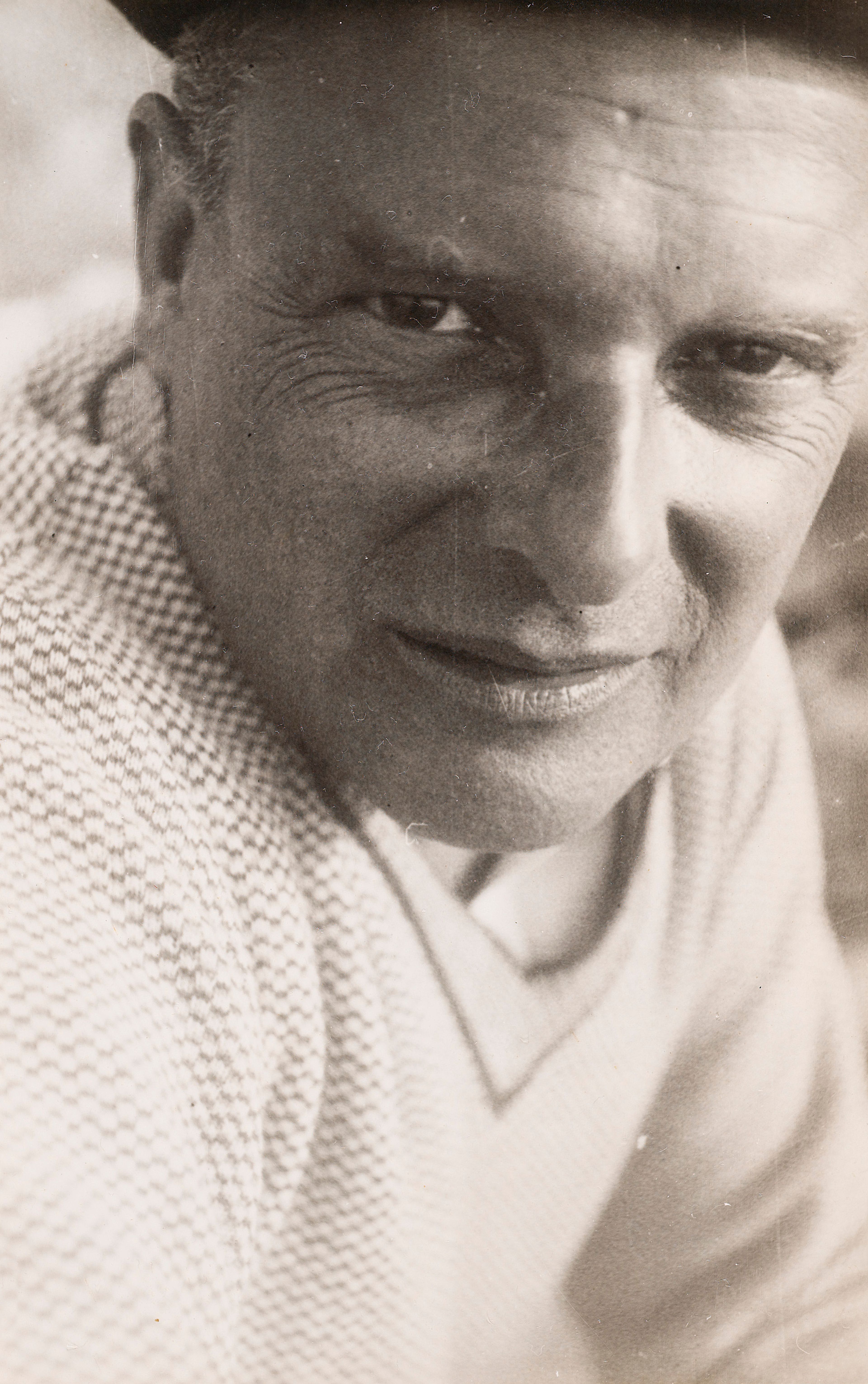

Paul Klee in Biarritz, 1929. Photo by Josef Albers © 2024 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

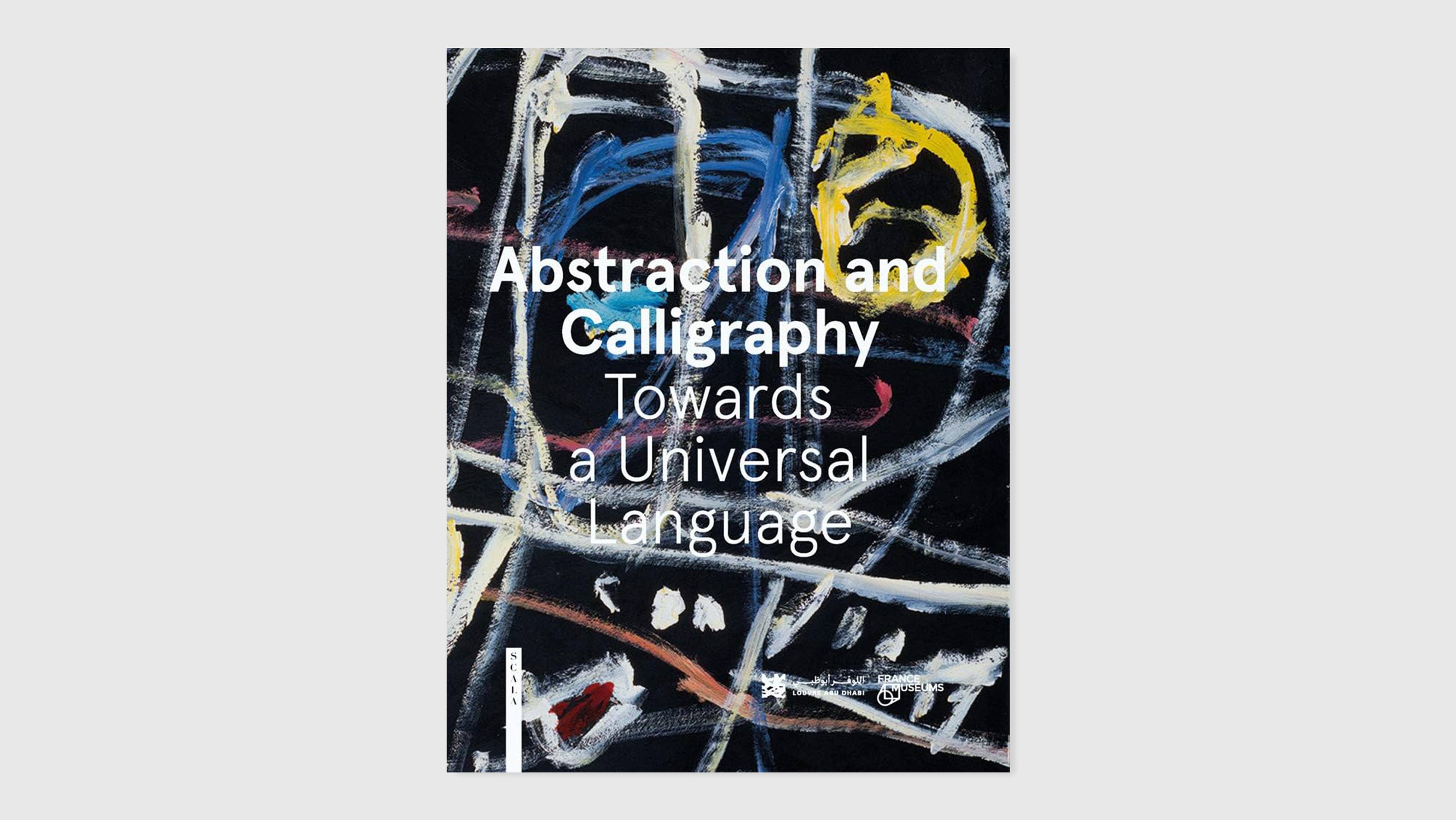

A pioneering modernist of unrivaled creative output, Paul Klee (1879–1940) counts among the truly defining artists of the twentieth century, exploring and expanding the terrain of avant-garde art through work that ranges from stunning colorist grids to evocative graphic productions. Klee taught for a decade, from 1921 to 1931, at the Bauhaus, the famed German art and design school, and the novelty of his work and ideas established him as one of the institution’s foremost instructors. He was associated with some of the most important art movements of the twentieth century, such as expressionism, cubism, and surrealism, yet his practice remained highly individualistic and distinct; it was never encapsulated by the concerns of a movement or reducible to the modernist binary of abstraction and figuration.

Klee was born a German citizen in Münchenbuchsee near Bern, Switzerland. In 1911, he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Thannhauser in Munich. In the same year, he met fellow artist Wassily Kandinsky and became acquainted with the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), exhibiting with them at their second show, in 1912. Later that year, after becoming familiar with the art of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Robert Delaunay during a trip to Paris, Klee began incorporating cubist and other innovative colorist techniques and ideas into his own distinct practice. Two years later, in 1914, Klee traveled to Tunisia with his friends the artists August Macke and Louis Moilliet, a revelatory experience that the artist credits with further awakening him to color. In 1921, he was appointed to the faculty of the Bauhaus by Walter Gropius, the founder and first director of the school, where he taught and worked as a "form master" from 1921 to 1925, while the school was in Weimar, and as a professor from 1926 to 1931, when the school was located in Dessau.

The renowned gallerist Hans Goltz, a fierce supporter of modern art and Paul Klee’s first general agent, from 1919 to 1925, staged a retrospective of Klee’s art in 1920 at his gallery in Munich. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the first director of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, had become familiar with Klee’s art in the 1920s and presented an exhibition of his work in March of 1930, the institution’s first solo show of a living European artist. In 1935, his work was the subject of major retrospectives at the Kunsthalle Bern and the Kunsthalle Basel. In 1940, shortly before he passed away, Klee had a solo exhibition of new work at the Kunsthaus Zürich.

Important posthumous presentations of Klee’s work include a traveling memorial exhibition in 1941 that was organized by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and toured additional venues across the United States, including the San Francisco Museum of Art. His work has been the subject of major retrospectives and traveling solo exhibitions at institutions including, among others, Tate Gallery, London (1945); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, which traveled to Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels (1957); Akademie der Künste, Berlin (1961); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1967 and 1993); Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris (1969–1970); Seibu Museum, Tokyo (1980); and The Museum of Modern Art, New York, which traveled to the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Kunstmuseum Bern (1987–1988).

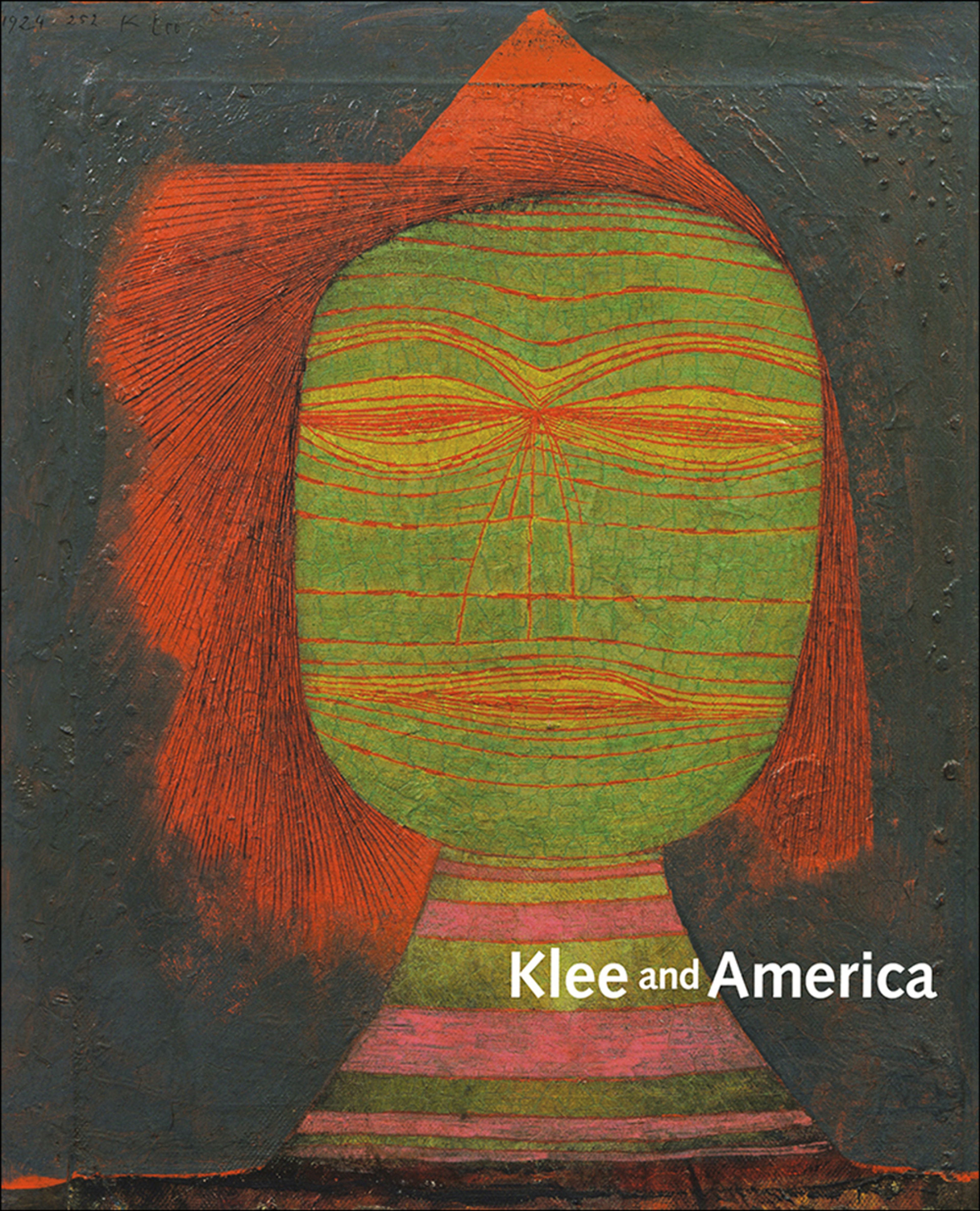

Since 2000, numerous exhibitions on Klee have explored various aspects of his art and career. From 2003 to 2004, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, presented Klee and Kandinsky: The Bauhaus Years. An exhibition focusing on Klee’s impact in the United States, Klee and America, was featured at the Neue Galerie, New York, and traveled to The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, and The Menil Collection, Houston, from 2006 to 2007. Paul Klee: Art in the Making 1883–1940 was shown at the National Museum of Modern Art (MOMAK), Kyoto, and traveled to the National Museum of Modern Art (MOMAT), Tokyo, in 2011.

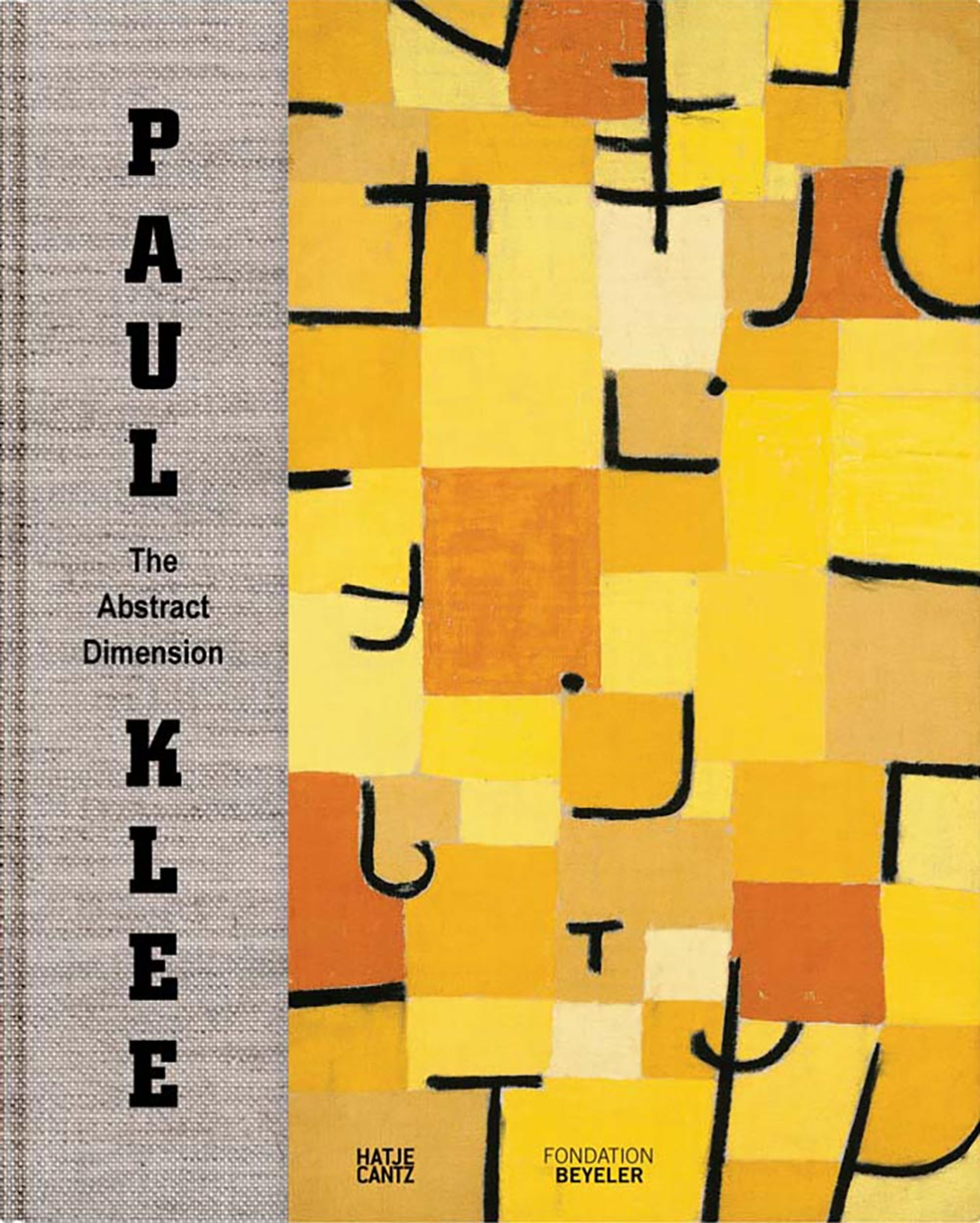

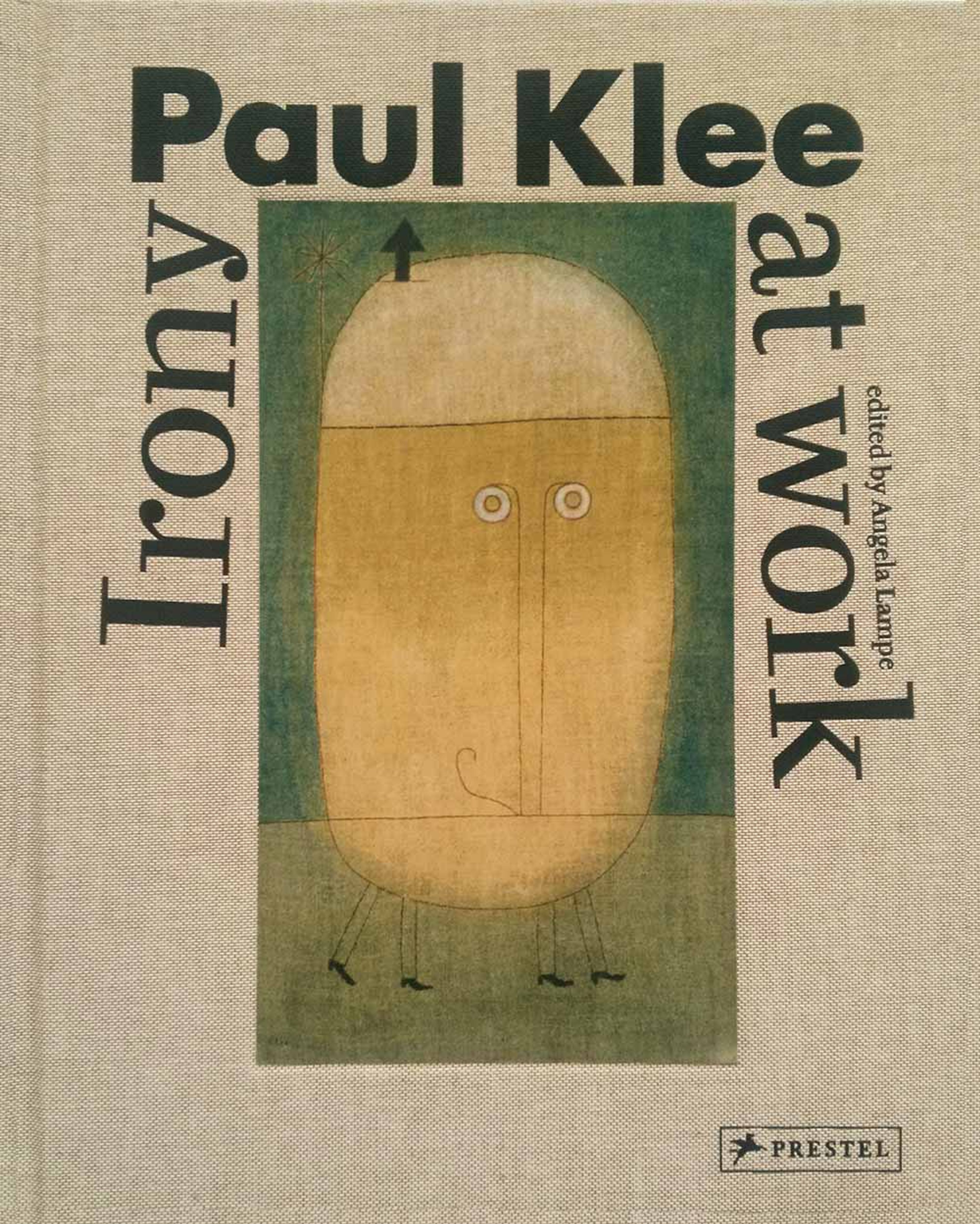

Among major exhibitions of his work during the past decade are The EY Exhibition: Paul Klee – Making Visible at Tate Modern, London from 2013 to 2014; the Centre Pompidou, Paris, held Paul Klee: Irony at Work in 2016; Fondation Beyeler, Basel, hosted the retrospective Paul Klee: The Abstract Dimension from 2017 to 2018; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, featured Paul Klee: Construction of Mystery in 2018; and Museo delle culture, Milan, presented Paul Klee: Alle origini dell’arte (Paul Klee: At the origins of art) from 2018 to 2019. In 2019, Paul Klee: Equilíbrio Instável debuted at Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, São Paulo, and traveled to Centro Cultural do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, and Centro Cultural do Brasil, Belo Horizonte. Klee in North Africa: 1914, Tunisia | Egypt, 1928 was on view at the Museum Berggruen, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin from 2020 to 2021. In 2022, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art presented the two-person exhibition Paul Klee & Lee Mullican: Outward Sight and Inner Vision. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, presented Paul Klee and the Secrets of Nature from 2022 into 2023. Paul Klee: Psychic Improvisation was on view at David Zwirner New York in 2024.

In 1947, after the death of Paul Klee’s widow, four prominent collectors in Bern established the Paul Klee Foundation, which was housed in the Kunstmuseum Bern until 2004. On the occasion of a large donation of works from the Klee Family, the foundation was absorbed into a new museum dedicated to the artist. In 2005, the Zentrum Paul Klee opened as an independent institution and research center with a building designed by Renzo Piano. Klee’s work is in the permanent collections of countless major museums around the world.