Yayoi Kusama Retrospective

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

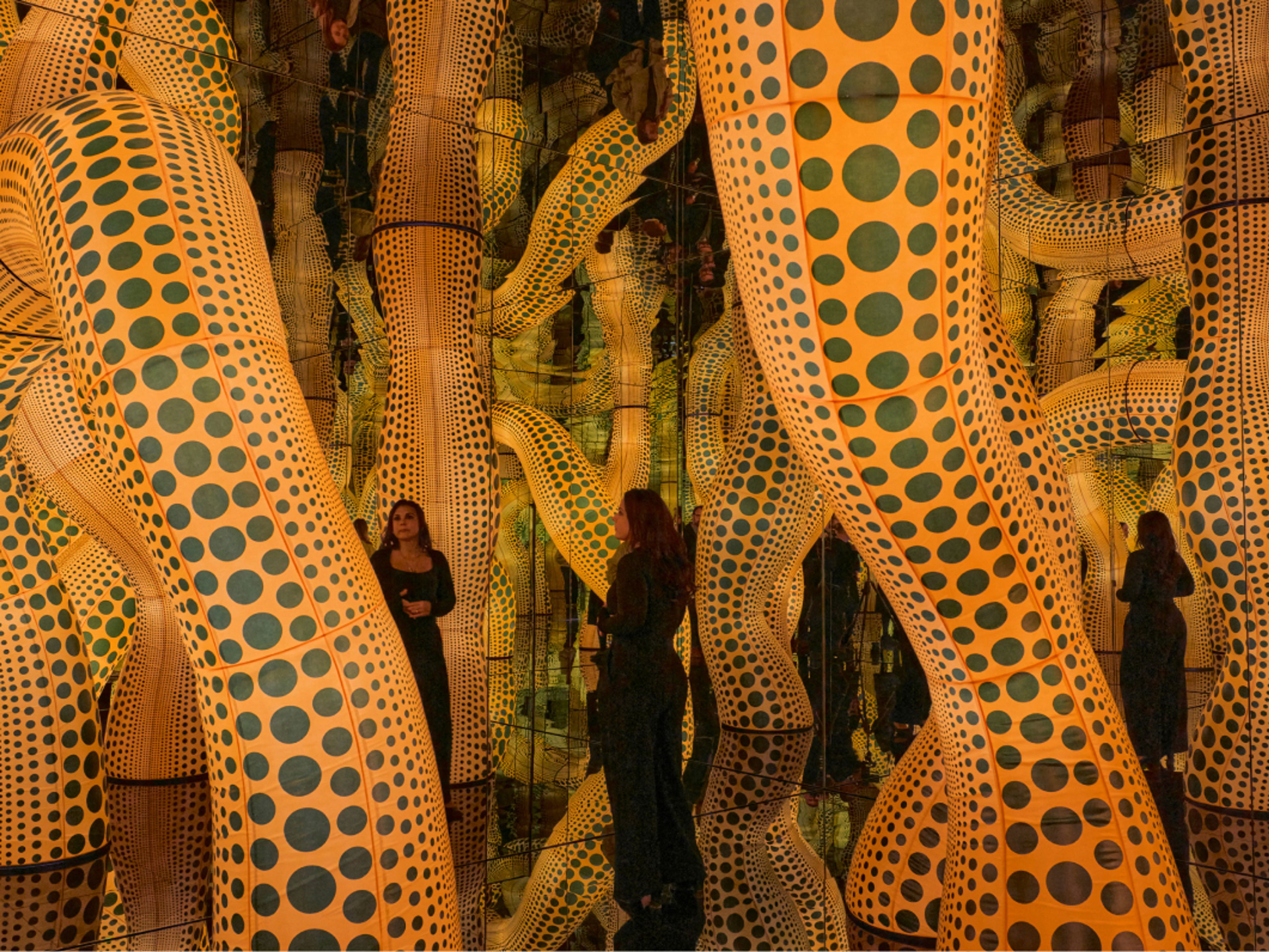

Installation view, Yayoi Kusama, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2025. Photo by Mark Niedermann © YAYOI KUSAMA

Kusama in her installation Narcissus Garden at the 33rd Venice Biennale, 1966. © YAYOI KUSAMA

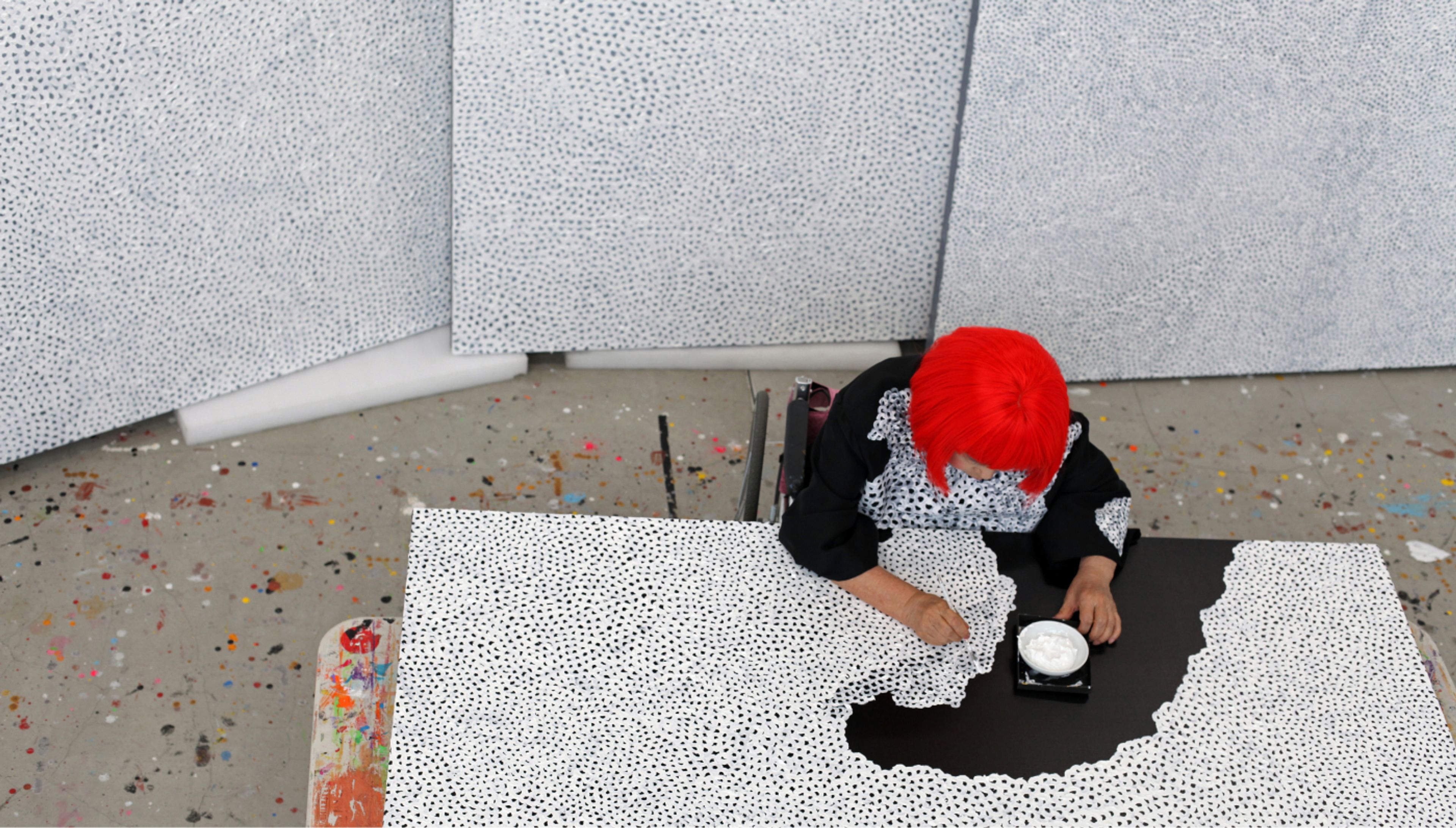

The artist at work in her studio, 2017. Courtesy Victoria Miro

Central to Kusama’s oeuvre is the concept of infinity—not merely as a formal device, but as a lived, spiritual, and psychological reality. Her hallmark motifs—polka dots, nets, mirrors, and repetitive forms—are more than aesthetic signatures; they reflect a profound meditation on the cycles of life and death, the dissolution of the self, and the desire for transcendence. As curators Leontine Coelewij, Stephan Diederich, and Mouna Mekouar write in their introduction to the exhibition catalogue, “the essential message at the heart of Kusama’s practice [is] a vision that transcends boundaries and dissolves definitions, revealing a profound interconnectedness between the self and the cosmos, the microcosm and the macrocosm. Over the course of her remarkable career, she has rendered the invisible rhythms of nature and the universe visible using a language that is deeply personal, poetic, and profoundly human.”

Installation view, Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room – The Hope of the Polka Dots Buried in Infinity Will Eternally Cover the Universe, 2025. In the exhibition Yayoi Kusama, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2025. Photo by Mark Niedermann © YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama, 1939. Photo courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo. © YAYOI KUSAMA

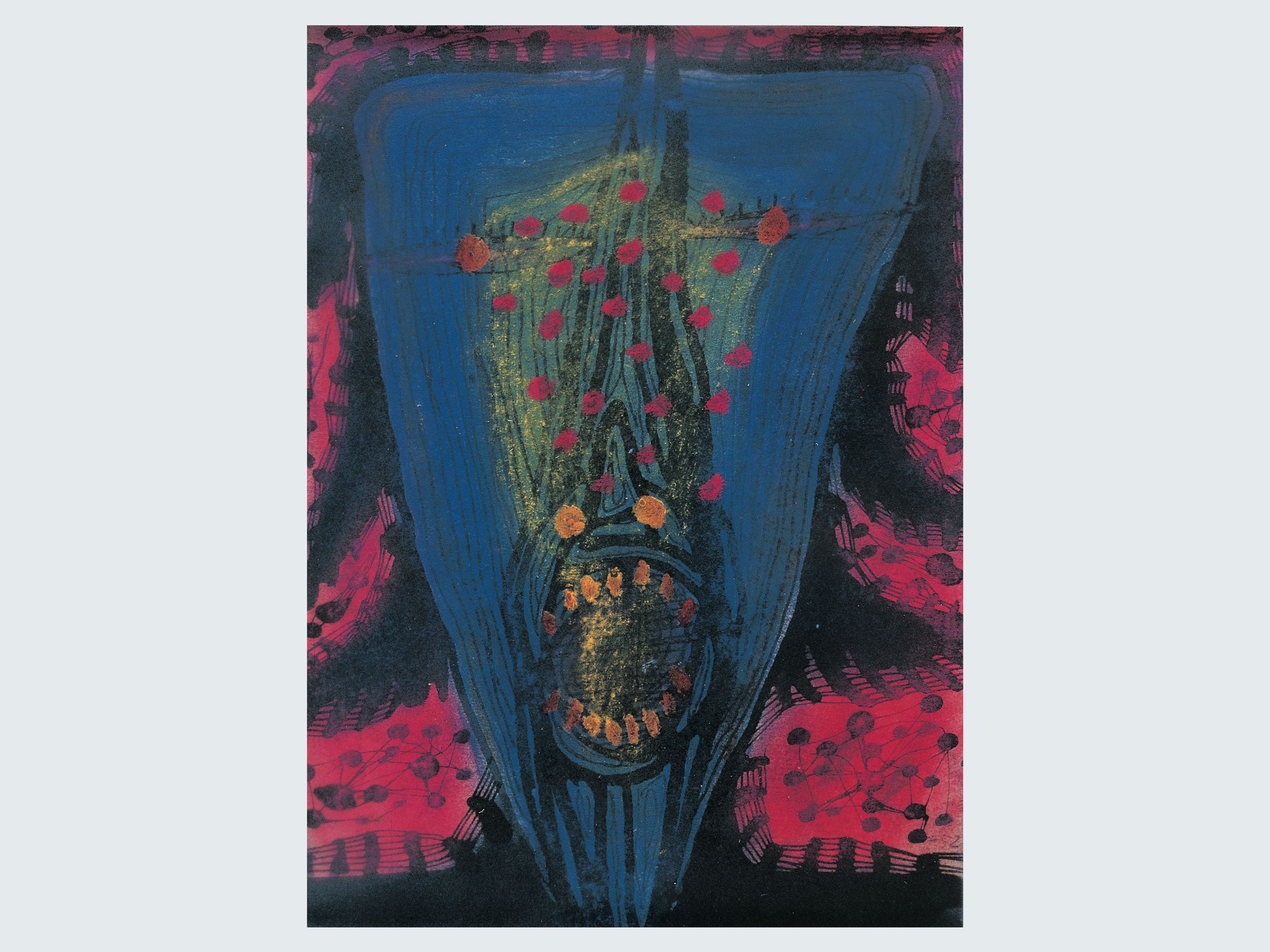

Yayoi Kusama, Screaming Girl, 1952. Oketa Collection, Tokyo. © YAYOI KUSAMA

The retrospective traces Kusama’s extraordinary journey to her internationally celebrated status today, starting with rarely seen paintings and watercolors made in the early 1950s in her hometown of Matsumoto, Japan. While raised in an affluent family, Kusama, born in 1929, felt the impact of her parents’ unhappy marriage. “Perhaps triggered or at least exacerbated by these family tensions,” the curators note in the catalogue, “Yayoi, then not yet ten years old, began to suffer from perceptual changes that manifested themselves in auditory and visual hallucinations, which would later be diagnosed as an obsessive-compulsive disorder. At times she heard animals and plants speaking to her, at other times she saw auras around things or experienced how repetitive patterns of flowers or dots spread across furniture, her own body, the entire room, and beyond. By indefatigably capturing the images of her altered perception in drawings, perhaps to reassure herself of their reality, Kusama, according to her own assessment, laid the foundation for her very own artistic language.”

“One day, after gazing at a pattern of red flowers on the tablecloth, I looked up to see that the ceiling, the windows, and the columns seemed to be plastered with the same red floral pattern. I saw the entire room, my entire body, and the entire universe covered with red flowers, and in that instant my soul was obliterated and I was restored, returned to infinity, to eternal time and absolute space. This was not illusion but reality itself. I was shocked to the depths of my soul. And my body was caught in that terrifying infinity net.”

—Yayoi Kusama, recalling her youth in her 2002 autobiography Infinity Net

Installation view, Yayoi Kusama, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2025. Photo by Mark Niedermann © YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama in her studio in New York with an early Infinity Net painting, 1961

Kusama interacting with a visitor to Narcissus Garden (1966), at the 33rd Venice Biennale. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice

The exhibition then follows Kusama’s bold move to New York in the late 1950s, where she played a formative role in the avant-garde and art scenes. She experienced a breakthrough with the first of her Infinity Net paintings. When they were exhibited in a solo show at the Brata Gallery in 1959, their qualities were instantly recognized by artists, critics, and curators. Among them was Donald Judd, who became a close friend for years, and the German curator and museum director Udo Kulterman, who put a large white Infinity Net in his legendary exhibition Monochrome Malerei (Monochrome Painting) at the Städtisches Museum Schloss Morsbroich in Leverkusen, Germany, in 1960—bringing Kusama to the attention of European audiences and into other important museum shows of the time.

“Yayoi Kusama is an original painter. The five white, very large paintings in this show are strong, advanced in concept and realized ... The effect is both complex and simple ... The expression transcends the question of whether it is Oriental or American. Although it is something of both, certainly of such Americans as Rothko, Still and Newman, it is not at all a synthesis and is thoroughly independent.”

—Donald Judd, in his 1959 ArtNews review of the Brata exhibition

In December 1963, Kusama had another breakthrough with her installation Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show at the Gertrude Stein Gallery in New York. A single rowboat was placed in the center of the room, while the walls were covered with 999 black-and-white reproductions of the boat sculpture. The rowboat featured Kusama’s now signature soft phallus-like fabric forms—an invention that led to her Accumulations sculptures and, as the catalogue introduction explains, was “an effort to confront her phallic anxieties and her aversion to sex in a typically excessive manner.” During these eventful years in New York—when Kusama was involved in the underground art scene and became known for her public performances and Happenings that dissolved the boundaries between art, society, and our environment—one work produced abroad stands out among others. Narcissus Garden represented Kusama’s unofficial participation in the Venice Biennale, in 1966; despite not being invited to present work in the exhibition, she created an arrangement of hundreds of chrome-plated balls on a lawn, which reflected the surroundings, the people, and the architecture. Narcissus Garden was made in reference to the Greek myth of the beauty who falls in love with his own reflection, and Kusama laid in the grass among the spheres and offered individual balls for sale with the pitch: “Your narcissism for sale: one piece 2 dollars.” This artwork represents Kusama’s careerlong project to bring the viewer into her work through participatory elements.

Yayoi Kusama, Everything about My Love, 2013. From the My Eternal Soul series (2009–2021). Collection of the artist. © YAYOI KUSAMA

At work in her Tokyo studio, 2014. Photo by Go Itami

Installation view of works from the Every Day I Pray For Love series. In the exhibition Yayoi Kusama, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2025. Photo by Mark Niedermann © YAYOI KUSAMA

Due to her ongoing health concerns, Kusama returned to Japan in 1973. In Tokyo, she continued to reinvent her artistic language in deeply personal ways. She also focused increasingly on her writing, publishing her first novel Manhattan Suicide Addict, a fictionalized account of her New York years, in 1978. Many novels and collections of poetry and short stories have followed in the decades since, as well as her 2002 autobiography. At the same time, Kusama began experimenting with printmaking starting in the late 1970s. She also continued what began with the Accumulation sculptures with boxes filled with snakelike forms and assembled into monumental works. And beginning in the late 1980s, Kusama began making large abstract paintings in bright acrylic colors, some which she arranged into wide expanses of many panels. During this period, she had her first institutional retrospective in Japan, at the Kitakyushu Municipal Art Museum in 1987, followed by her first American museum retrospective in 1989, at New York’s Center for International Contemporary Arts (CICA), confirming her global reputation and influence. In 1993, almost three decades after the creation of Narcissus Garden, Kusama was invited to be the first living woman artist to represent Japan at the 45th Venice Biennale. New works made after her return to Japan were also presented in solo exhibitions dedicated to both her New York and post-New York output in institutions like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. In addition to new sculptural forms, Infinity Mirror Rooms, and immersive environments, the work that Kusama has created over the last few decades, by now well known to most, includes the vibrant My Eternal Soul paintings. Begun in 2009, these works—intense, vivid, both abstract and figurative—are highly personal for the artist. Their use of repetition reflects the history of obsession in Kusama’s work, which itself comes from her desire to make art that is at once autobiographical and can exist outside the confines of the self. Likewise, her ongoing series of paintings Every Day I Pray For Love is a way for the artist to process her own life and work. As the catalogue notes, according to Kusama these colorful paintings “contain motifs and imagery from her youth, coming full circle in a never-ending abundance of Kusama’s messages to the world.”

The artist at work in her studio, 2017. Courtesy Victoria Miro

Installation view, Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room – The Hope of the Polka Dots Buried in Infinity Will Eternally Cover the Universe, 2025. In the exhibition Yayoi Kusama, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2025. Photo by Mark Niedermann © YAYOI KUSAMA

Plan Your Visit

Yayoi Kusama is on view through January 25, 2026 at Fondation Beyeler, in Riehen, outside of Basel, Switzerland. You can reserve tickets here.

Learn more about Yayoi Kusama