Essay by Teju Cole

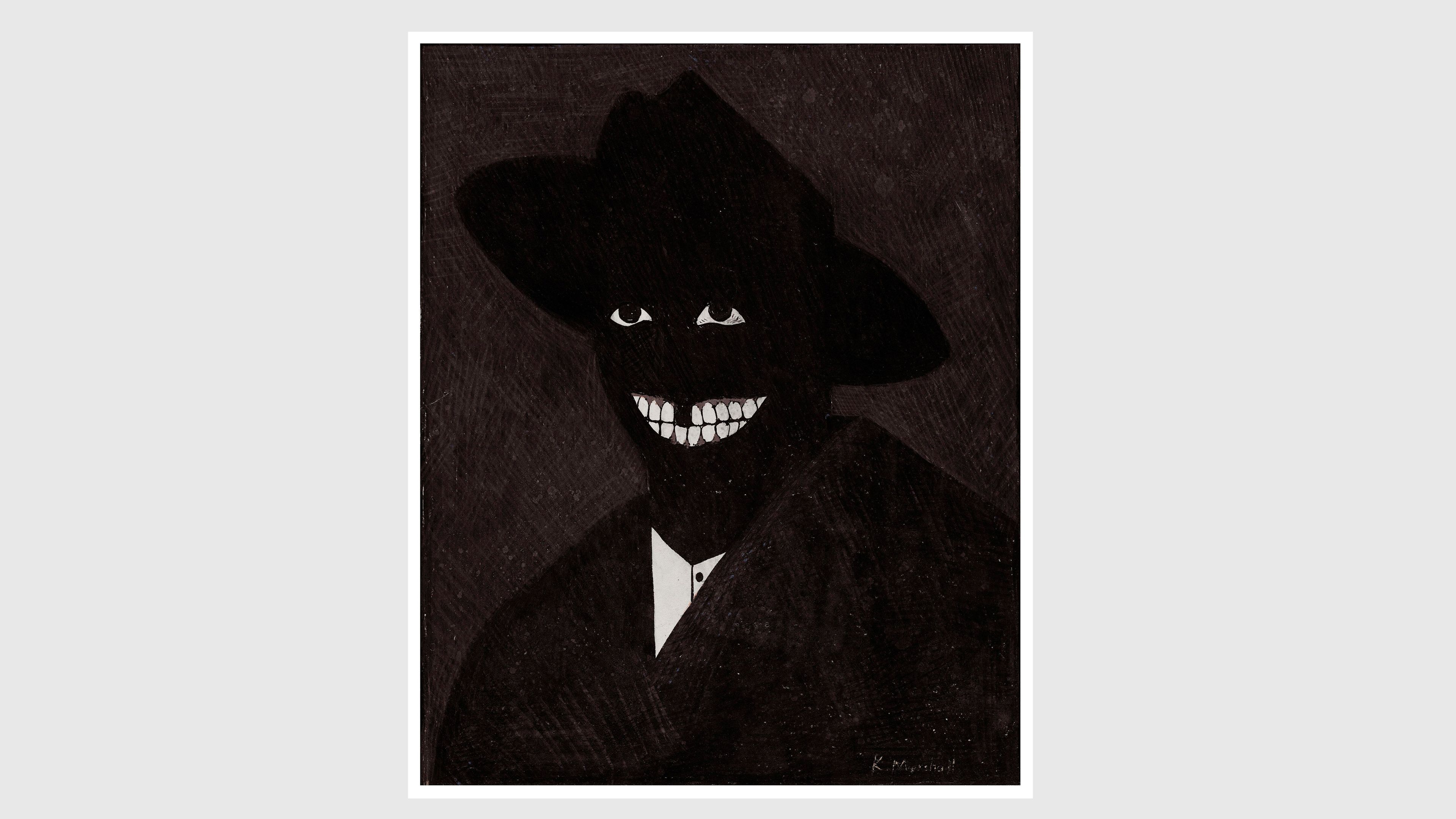

After A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self (1980; p. 10), the shadow henceforth is no longer only an extension of the self, or a riff on it, or a mere variation on it. It is the self, and the self is the shadow. Shadow and substance have played around each other a long time. Since before Shakespeare wrote: “What is your substance, whereof are you made, / That millions of strange shadows on you tend?” In Kerry James Marshall, substance and shadow merge, as in a total eclipse, transfiguring the perceptual landscape.

• Kora, a young woman in the Peloponnesian city-state of Sicyon, had a lover who was departing. To preserve his memory, she drew a careful and sinuous line around his shadow. (The account, taken to be the originary myth of portraiture, is recounted in Book XXXV of Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia.) Kora’s father, Butades, filled the outline of the shadow with clay and fired it alongside his pots. A means of remembering what would otherwise have been forgotten. A shadow made permanent.

• Have you ever heard anything so absurd? Africa, sun-stunned and light–inundated Africa, described as the “Dark Continent”? Something more than metaphor must be at play here. It must be that some other darkness is being displaced. The term became popular as part of the colonial enterprise of the nineteenth century. It submerged and effaced thousands of years of interaction between Europe and Africa—this was the kind of distance colonialists needed. Something was being pretended at here, some familiarity posing as lack of familiarity, some darkness that was a symbolic representation not of those so-named but of those who did the naming. • Kerry James Marshall is looking for what’s not there. No, not quite. Kerry James Marshall is looking for what is there but not seen. Well, almost. Try again. Kerry James Marshall is looking for what is there but not seen by them. That’s it.

Marshall wants to “address absence with a capital A.” Address, absence, a, A—that’s how to begin an alphabet, an anecdote, an account. • A silhouette is a traced, mechanically drawn, or free-drawn shadow filled in with black. It might be an artistic shadow materially made of black, as in a cutout. This by now ordinary word has a surprising origin: Étienne de Silhouette, a short-term finance minister to Louis XV in 1759, is its eponym. Silhouette was infamously stringent and cheap, and anything thought of as insubstantial or miserly was thus denoted as being à la Silhouette.

Auguste Edouart, who settled in London in 1814, was a leading portraitist in black-paper profiles. He called himself “the black shade man.” Skiagram, shadowgraph, shade were some of the terms for his art, until Edouart helped the now favored term stick: silhouette. • The popularity of photography after Louis Daguerre’s announcement in 1839 inaugurated a loss of interest in silhouettes. But the public imagination was nevertheless haunted by the idea of fixing shadows, making them permanent. With the rise in popularity of cartes de visite, certain daguerreotypists urged their prospective clients to “secure the shadow ’ere the substance fade.”

What they were calling for was not mere portraiture but, specifically, portraiture of the recently beloved dead. Life, on its way to forgetting, was detained one final time in postmortem portraits. • It got dark.

“I am invisible, understand,” the unnamed narrator says in Invisible Man, “simply because people refuse to see me.” When he arrives at Liberty Paints, he’s set to work mixing a shade of white called Optic White. Optic White is created by mixing the white foundation with ten drops of a particular black chemical. Thus mixed, Optic White comes out dazzlingly white: “If It’s Optic White, It’s the Right White.” Dazzling white. The black is in there, though. Address absence with a capital A.

• With what measure of innocence can a black American encounter and absorb any display of prices or pricing? What shadow falls perpetually on sales, on selling, on those whose history was in part to have been sold, as goods are sold? The thought cannot be constantly overt—no one could live that way—but surely it irradiates any encounter with price, with pricing. Slavery was a profit-and-loss activity in living color.

In criminology and sociology, the amount of undiscovered or unreported crime is called the “dark figure.” • “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” The psalmist speaks not of the valley of death but, in a surprising extension, of the valley of the shadow of death. Some Christian interpretation, such as that by Clement of Rome in 96 ce, has it as a prophecy of the journey of Christ through the valley of death. The phrase “shadow of death” recurs in the Hebrew Bible—in addition to Psalm 23, it is also found in Job 3:5, Isaiah 9:2, and elsewhere in the psalms. One rabbinic midrash reads "the valley of the shadow of death" as purgatory, a temporary state of torment that God will eventually alleviate. Another midrash, from the early medieval Midrash Tehillim, locates it in actual space, the desert of Ziph, where David is feeling enemies: Saul, Doeg, Ahithophel. But when the speaker implores God, in Psalm 17:8, "Keep me as the apple of the eye, hide me under the shadow of thy wings," the positive sense of the shadow emerges. A cooling place, a protection ad bulwark, not a threat to be overmastered but a refuge to be enclosed in. • In the shadow of a cave on the limestone plateau of the Ardèche River, by the light of flares and torches, responding with intuition and skill to the swells and dips of a rock face, human beings painted. The images must have danced in the inconstant light of the torches: lions, aurochs, cave bears, woolly rhinoceroses–the animals of the real and dream worlds. These creatures, many of which are now extinct, were likely depicted for shamanistic purposes. Nearer the entrance of the cave, the painting was done with red ocher. Deeper inside, the preferred color was black, a black pigment from charcoal, soot–carbon black, the residue of fire. These early painters would return, bearing their torches, and the animals they had rendered in black would shimmer back to life. Permanent shadows, thirty thousand years old, and from there grew and spread the cultural possibility of black: sacred and reviled and beloved. • When I was a boy on the Dark Continent, everyone at my school, with the exception of one or two Indian kids, or the very rare white foreign student, was black. This was in Lagos, and there was nothing dark about the continent. We made fun of one another's appearance as children everywhere tend to do. We were most interested in names that finely determined where on the light-to-dark spectrum each of us stood. Not that we cared either way who was light or who was dark. Thousands of miles away from European or New World racism, we were interested in making fun of difference only for its own sake. The lighter-skinned boys we called "yellow" or "oyinbo" (Yoruba for "white person"). Middle tones were not really named, since what is considered the standard needs no mockery. The darker boys had a variety of names: "blackie" or "dudu" (Yoruba for "black"). A good friend of mine, a dark-skinned boy, was Big Stout. His sister, by the logic of the schoolyard, was Small Stout. Big Stout was well loved, and he was also called, from time to time, Shadow. A black shade man. • The chromatic value of a color is its relative lightness or darkness. This statement, which may be read in the obvious sociological ways, is also a statement of technical fact in painterly practice. The chromatic value of a color is distinct from its saturation or temperature. Ivory black is black with a brown tint; it was traditionally made of ivory but its now usually made from animal bones. Mars black has a red tint and a warm temperature. Lamp black is dense, bluish black, a carbon pigment. "Black art," Faith Ringgold has said, "must use its own color black to recreate its own light, since that color is the most immediate black truth." • God made night and day–organized the distribution of shadow. The earth's shadow where it is not reached by the sun, the moon's shadow to determine what kind of night a night is. "The night has a love for throwing its shadows around a man / a bridge, a horse, the gun, a grave," wrote Charles Olson. "Half our days we pass in the shadow of the earth," wrote Thomas Browne. All continent are dark, half the time, but the darkness is not empty. • In 1815, Charles Catton Jr., a landscape painter was living and working on a Hudson River Valley farm. Catton was displeased that his slave Robert was visiting a young woman, also enslaved, on a neighboring farm. With his son's help, Catton beat Robert severely, almost to the death. Robert had been visiting Isabella (known as Belle). After the near homicide by the Cattons, Robert and Belle were not allowed to see each other ever again. Robert died a few years later, and Belle remained haunted by the injustice all her life. Some works by Catton are held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Rijksmuseum. Belle escaped from slavery in 1826. In 1843, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. • Every painter is in the history of painting. What makes a given painter interesting, one of the things that gives a painter a chance to be interesting, is his or her sense of where he or she sits in the lineage. The painters too indebted to their forbears place themselves too early in the timeline, and their work has all the weakness of a nostalgic position. Those at the opposite extreme, whose work speaks only to the future, can be judged only by the future (and the future will find most of them wanting). I am drawn to those painters who are in a proper present tense. I am drawn to the painters who have an ideally calibrated relationship with what painting has been. They manifest what painting is and allow for what painting could come to be. Such artists are convincingly contemporary, their practices and gestures confirming their inheritance of the lineage. As custodians of the history of painting, they know their place in it. They are just in time, and right on time. • In Akira Kurosawa's Kagemusha (1980), the shogun dies and his advisers decide to keep the death a secret. The shogun is replaced in ceremonial settings by a body double, a "shadow warrior". Gradually, something no less poignant for being predictable happens: the shadow warrior begins to feel in himself the power and bodily authority of the real shogun. The shadow begins to act like the real body, to the astonishment and dismay of the courtiers. The shadow, one might say, eclipses the substance. • In Addis Ababa, I see Julie Mehretu's Conjured Parts (tongues)(2015–2016; opposite), a painting made with a host of black marks. The painting pulses with murmurs and possibilities. I am back in the Chauvet Cave in 30,000 BCE, I am inside an Amharic manuscript, I am in a basement club festooned with graffiti, I am inside a forest at night during a rainstorm, a Twombly in negative, I am written and overwritten, a murky palimpsest. I am speaking in tongues. Speaking of tongues: in Sri Lanka, eating the tongue of the thalagoya, a monitor lizard, is believed to give one the gift of eloquence. • The word "underpainting" summons up technical reverie. The underpainting is one of the means by which a painter conveys his or her disegno onto the surface of the panel or canvas. It established the structures, contrasts, and tonal values that the overpainting will later accentuate. The query "What is underpainting?" associatively suggests another query: "What is under painting?" Or: "What is under the history of painting?" • The Wallace Collection in London holds Rembrandt's 1632 painting Jean Pellicorne with His Son Caspar. In the dual portrait, the father wears all black, save for his white lace neck ruff and sleeves, and the son, about four years old, wears brown. The painting is in the detailed and somewhat glassy style of Rebrandt's paintings from the early 1630s, after he moved to Amsterdam from Leiden, the period in which he fully came into his own as a master painter and garnered excited patronage. In the painting, Jean Pellicorne did indeed become very wealthy, in part by being a slave trader. In 1677, for instance, he signed, along with others, a contract to supply eighteen hundred slaves to the Spanish West Indies. • When a doctor places an X-ray on the screen, we still our breath. Something is about to signified. It is a calling to attention. Our untrained eyes cannot interpret this cluster of shadow, but to the doctor's eye, the shadows are legible. Some of them could be malign or, if there be mercy, all of them could be "unremarkable." David Hammons's Injustice Case (1970), a body print in grisaille, presents like an X-ray. This black body, remarkable, framed by the American flag, sees through what is not seen by them. • Kerry James Marshall's Untitled (Underpainting) (2017; pp. 42–32) is a coloristic field of blacks and browns. It depicts black people in a complex pictorial space of a museum gallery. The gallery is seen from two perspectives. Painting is essentially flat on the surface, even allowing for impasto. It works two-dimensionally and either actively courts illusion or actively subverts it. Untitled (Underpainting) does both, placing itself in dialogue with paintings about looking by Velázquez (a master of black), Vermeer, Courbet, Manet (another master of black), and with previous work by Marshall himself. But Untitled (Underpainting) does even more. It addresses a different kind of illusion: what is under painting, the black that has been there all along, but not seen by them. • In 1875, Eadweard Muybridge boarded a steamship and headed to Panama. He had just been acquitted of shooting dead Major Harry Larkyns, his wife's lover. (It was ruled justifiable homicide.) During this exile, he went also to Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. His famous studies of animal locomotion still lay in the future. The plate glass photographic techniques used by nineteenth-cetury photographers were hypersensitive to blue light. This meant that skies were often washed-out, white, in the print. Photographers frequently combined two or more exposures in the making of a final print–one for the landscape, and another with a shorter exposure time, for the sky–to allow for detail to emerge in both sections. Muybridge was a virtuoso of this practice, and he often placed an unrelated sky above a landscape, so that his pictures would end up being fictions that exist on paper, with only a faint relationship to the real world. Cloud studies especially preoccupied him during his Central American sojourn. How could the fugitive detail and subtlety of these white clouds be properly registered? Again and again, Muybridge went at the problem, creating an album of shaded whites. • In the West Indies–as V.S. Naipaul notes in The Middle Passage (1962)–the gradations of skin color were more stringently ordered and made more songlike and absurd: "white, fusty, musty, dusty, tea, coffee, cocoa, light black, black, dark black." • A black soft-sided quadrilateral with a bluish tint advancing, or receding, in a field of black with a purple or neutral tint: in his late paintings, Rothko attempted to evoke and even assert the sublime. Black became for him what white was for Muybridge in his cloud-chasing days: a full spectrum of tonal possibility. His inclination was that there is a lot to see inside black, though most of what he saw was the valley of the shadow of death. Rothko inhabited the sorrowful wing of black's possibility. The pictures were not generative, consoling, joyful. • A talk given by Toni Morrison in May 1975 draws my attention to the dispassionate language and affect of certain historical documents. This affect is palpable particularly in those documents that concern themselves with profit. She cites Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957. I look it up–the edition published in September 1975– and it is, as expected, meticulous. In section Z, which addresses "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics," some of the itemized sections are as follows: Coal exported from James River ports in Virginia, destination, 1758–1765 Pig iron exported to England, by colony, 1723–1776 Bar iron imported from England by American Colonies, 1710–1750 Value of furs imported to England by British Continental Colonies, 1700–1775 Indigo and silk exported from South Carolina and Georgia, 1747–1788 Value of commodity exports and imports, earnings, and value of slaves imported into British North American Colonies, 1768–1772 Rice exported from Charleston, S.C., by destination, 1717–1766 Pitch, tar, and turpentine exported from Charleston, S.C., 1725–1774 Coal. Pig iron. Bar iron. Furs. Indigo and silk. Slaves. Rice. Pitch, tar, and turpentine. I'm haunted by the word "profit." I am lost when I contemplate "value." Their meanings slip from my grip. The amount of unreported crime is called the "dark figure." • Man in Window (1987; p. 20) by Roy DeCarava is dense with black information. The man seen in the photograph is black, the curtains around the window are black, the room in which he sits in black, the light that emanates from the scene is black. One might be inclined to read them as different shades of gray, but this image, like so many be DeCarave, is multivocally black. Out of those black tones, the form rises to the surface, and here, there is relation, there is consolation, and recognition. There's both magic and lineage in this window. Betye Saar's Black Girl's Window (1969) echoes to one side of it. Kerry James Marshall's untitled 2018 painting (a black girl seen through a black-framed window) echoes to the other. Timeliness is being in time and being on time. Work conversant with the history of art, and in conversation with it, is timely. • From 1864 onward, Sojourner Truth owned the copyright of her cartes de visite, on which she printed the legend: "I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance." These images were used to raise funds for antislavery causes. Truth sold the Shadow (the photograph of herself) to support the Substance (her own substantial body, and the substantive cause of abolition). Contrast the commercial daguerreotypists' "Secure the shadow 'ere the substance fade" with Truth's "I Sell the Show to Support the Substance": it is the difference between working around death and working for life. I sell. The one who was sold (sold at an auction when she was nine years old for one hundred dollars, along with a flock of sheep) now has the agency to sell. I sell. But where the body was sold, it is now the image, the idea, that is sold, to support the body. This is an ethic of seeing and liberty. • "Blackness is non-negotiable in those pictures," says Kerry James Marshall. Black with yellow ocher. Black with raw umber. Black with a certain blue. Black with another kind of blue. Carbon black, from soot. Mars black, from iron oxide. Ivory black, from white bone burned. Black, black, black, black, black, black, black. Seven kinds of black, an infinity. Excerpted from Kerry James Marshall: History of Painting.