By Ha Duong

2021

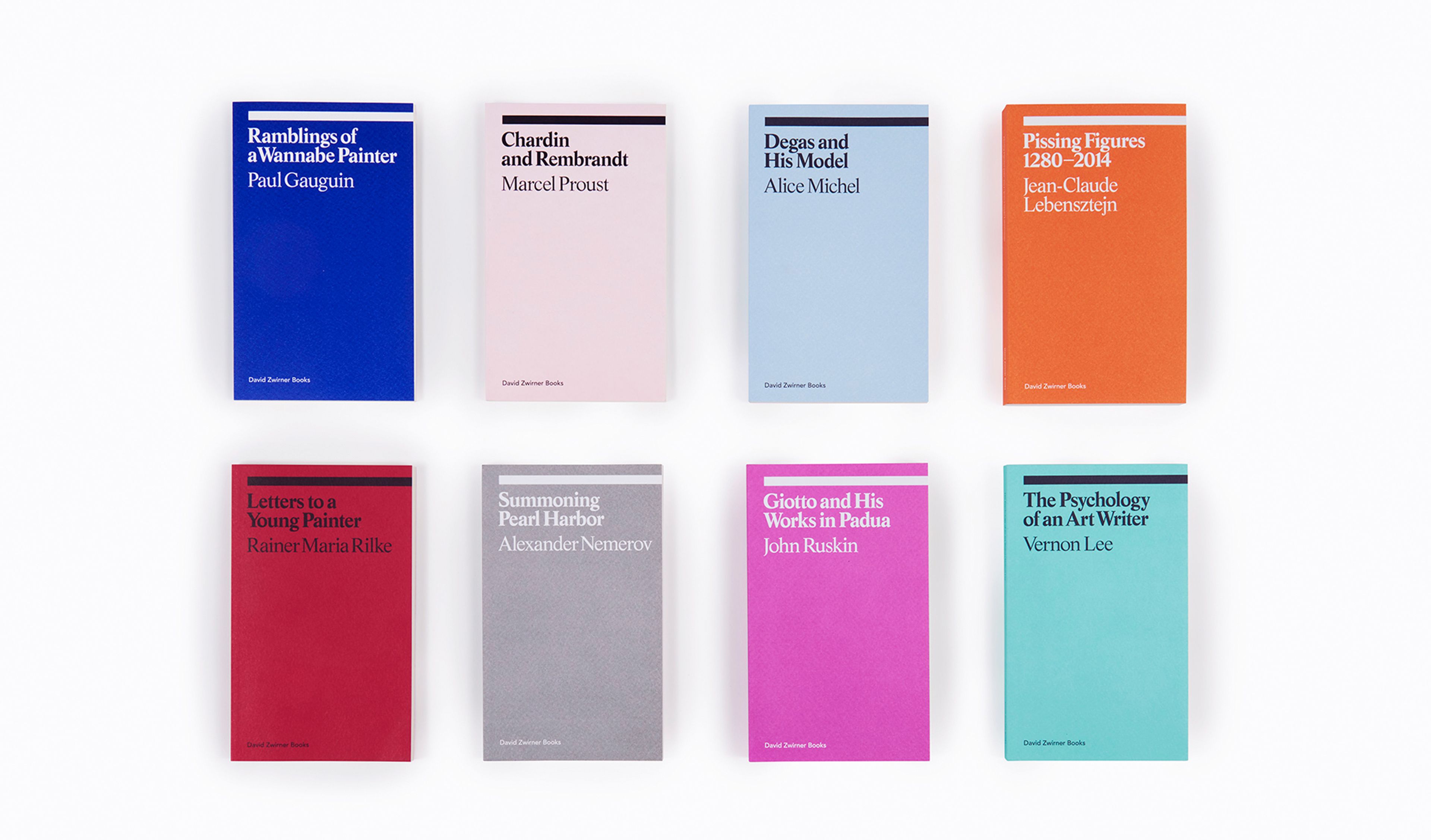

Since the late 1990s, the artist Liu Ye has painted books in all matter of form, angle, and content—open books, empty books, stacks of books, books being held, and books being read. Born the son of a children’s book author at the height of the Cultural Revolution, Liu grew up surrounded by both sanctioned and illicit literature, nurturing a lifelong appreciation of the book form that extends into his art practice. His meticulous paintings, which have been compiled in the new David Zwirner Books title Liu Ye: The Book Paintings, use books as subjects—almost like a rotating cast of characters—and as references, opening up the surface of his paintings to broader cultural meaning. Some of the books are anonymous, others are scrupulously reproduced down to the curve of each letter. The books, some from Liu’s own library, range from Piet Mondrian’s Rot Gelb Blau, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and Dick Bruna’s Miffy the Artist. Here is our guide to each (identifiable) book painted by Liu.

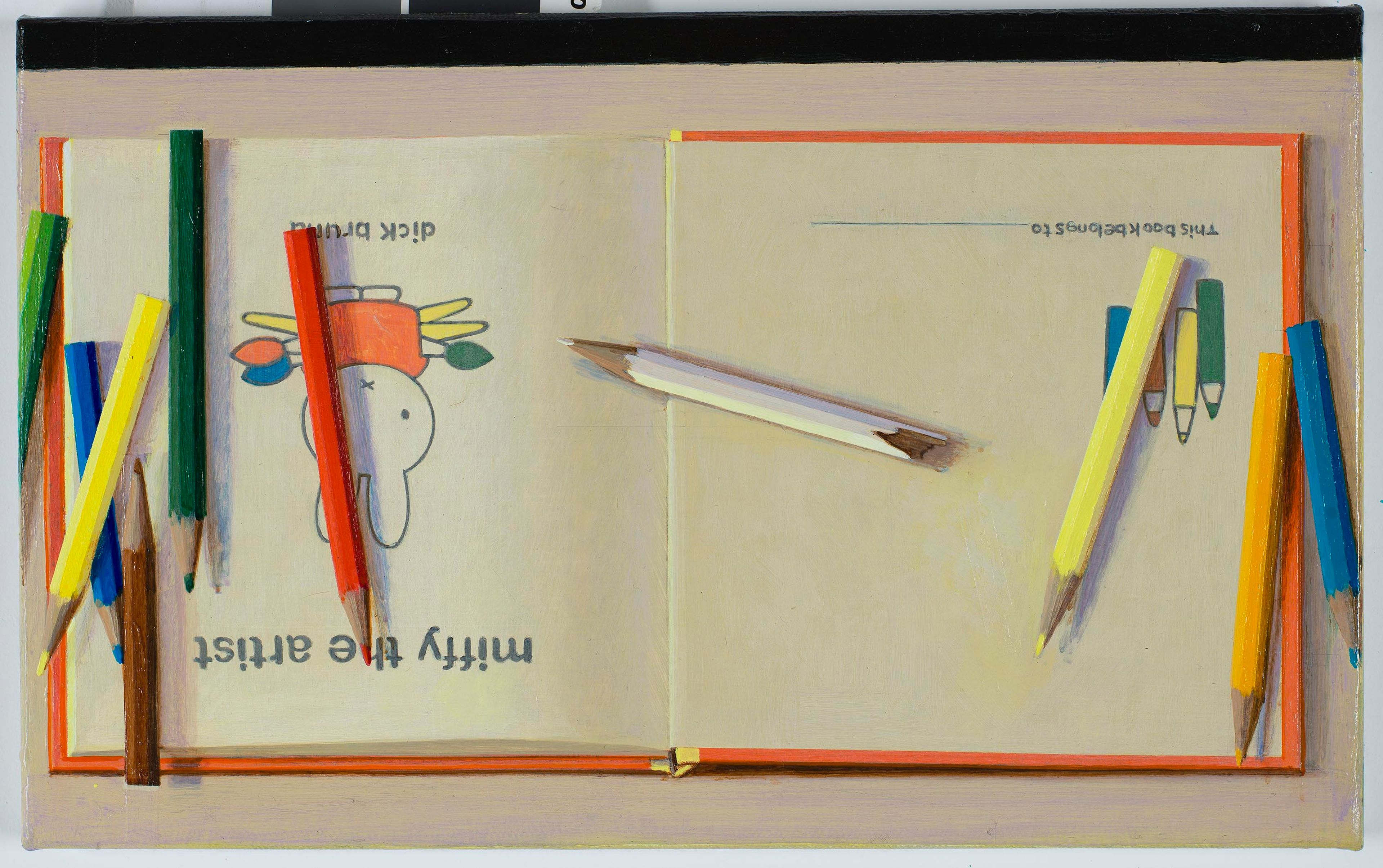

Dick Bruna’s Miffy the Artist

It was during a six-month residency at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam in 1998 when Liu first encountered Miffy—an uber-cute, expressionless rabbit character. Created by the Dutch artist Dick Bruna in 1955, Miffy eventually became ubiquitous in the Netherlands: “It’s a Dutch national figure, a symbol.… I immediately felt it had an incredible form,” Liu explained in an interview with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. “Miffy is a very simple creation. There’s no expression, but a lot is said.… Dick Bruna is my Leonardo da Vinci.” Miffy is a frequent subject in Liu’s work, and a painting of a spread from the book Miffy the Artist has a self-referential sense of humor. The book pages Liu reproduced in the painting contain illustrations of colored pencils in one corner. On top of this Liu has painted what are presumably “actual” colored pencils—except, of course, that they are colored pencils in a painting (which are now pages in a book about his book paintings).

Image: Liu Ye, Miffy the Artist, 2013

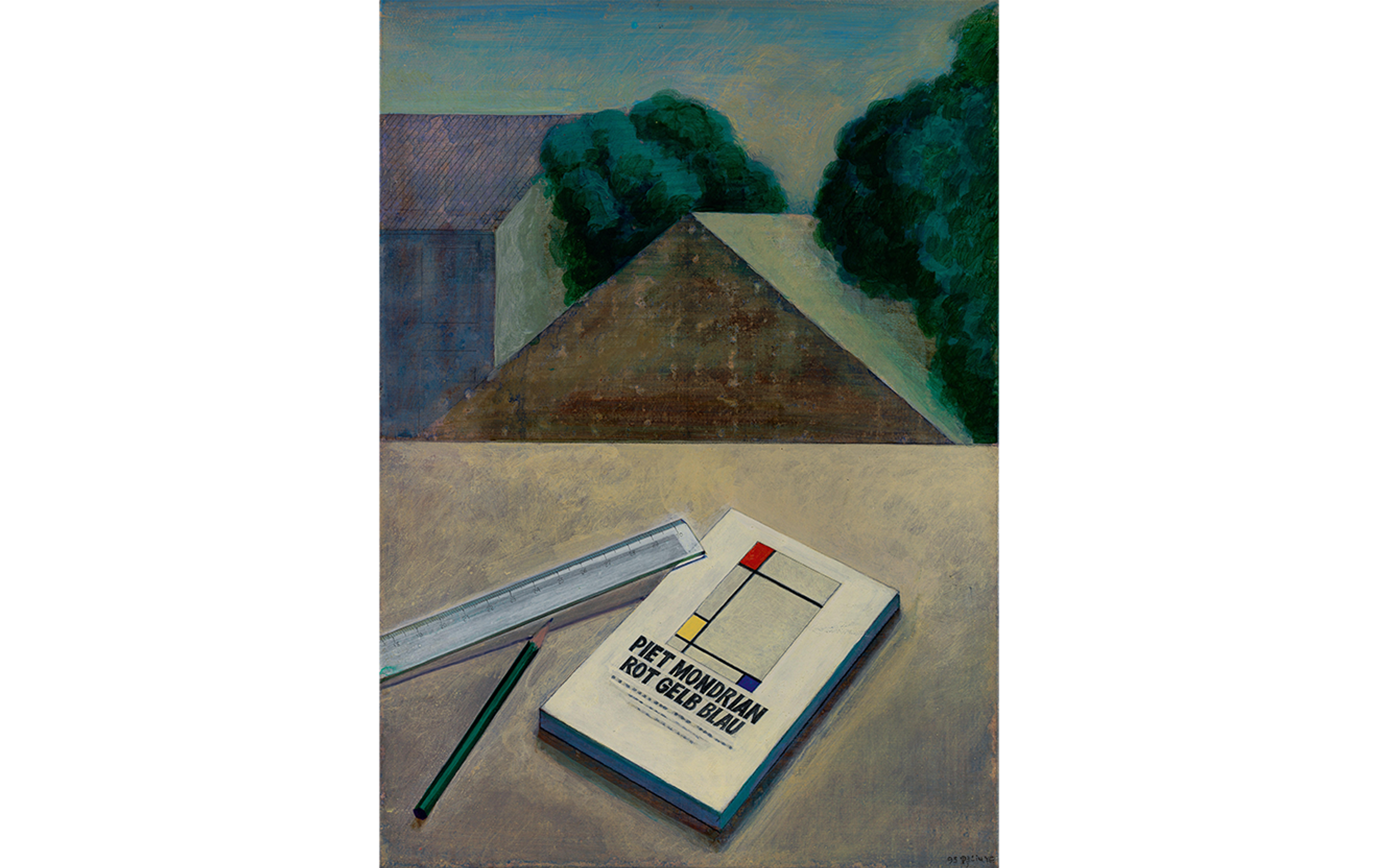

Piet Mondrian Rot Gelb Blau

After Liu encountered his work while studying industrial design in Beijing, Mondrian has appeared in Liu’s paintings in countless ways: we see Mondrian paintings paired with Miffy, Mondrian books in the hands of a reader, Mondrian paintings hanging on gallery walls, or more generally, Mondrian lingering in Liu’s color and composition. One book Liu paints repeatedly is this 1995 monograph on Mondrian’s painting and composition using the colors red, yellow, and blue. Mondrian’s influence on Liu may run deep, but Liu’s painting Scale (1995) rebels against the Dutch painter’s rigorous right angles by leaning Rot Gelb Blau at forty-five degrees. And in Mondrian in the Morning (2000), a green-skirted young girl stands in front of a Mondrian painting, in part because Mondrian hated green. “Sometimes I feel he is my teacher or father,” explained Liu. “I love him so much that I have to work against him sometimes.”

Image: Liu Ye, Scale, 1995

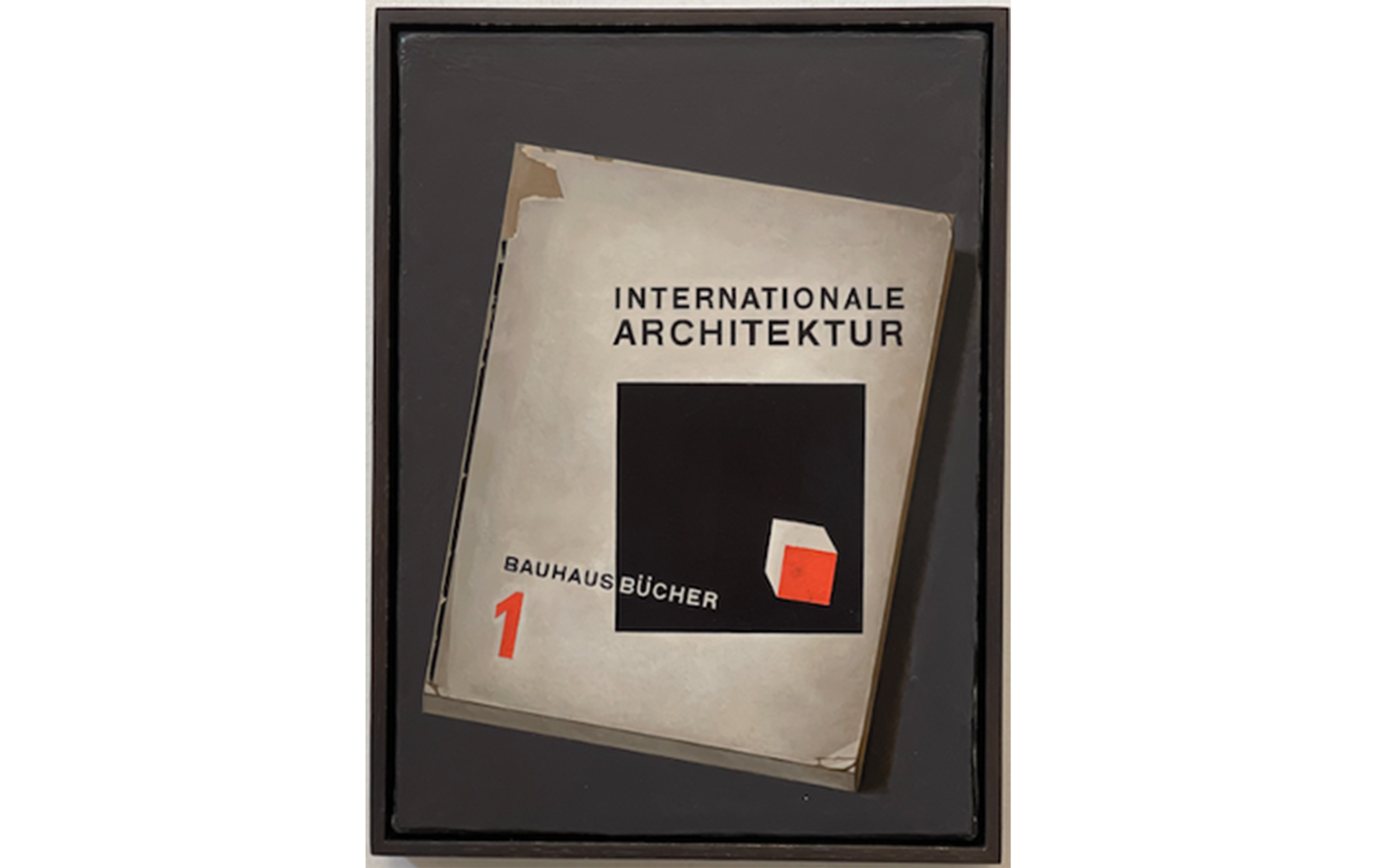

Walter Gropius’s Internationale architektur Bauhaus buecher No. 1

The Bauhausbücher—or Bauhaus Books—was a series conceived by the German architect Walter Gropius and Hungarian painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy. Between 1925 and 1930, fourteen titles were published, with contributions from Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and many others. Intended to communicate Bauhaus philosophy, the first book in the series, Gropius’s Internationale architektur, gave early twentieth-century readers the skinny on the architecture of their time, and what Gropius saw as the guiding principles of the then emerging international avant-garde. Liu encountered the Bauhaus as a young art student in Berlin, and has since painted other Bauhaus books, architectural facades, and Oskar Schlemmer’s ballet dancers.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 31 (Internationale architektur Bauhaus buecher No. 1, Albert Langen Verlag, Muenchen, 1925), 2020

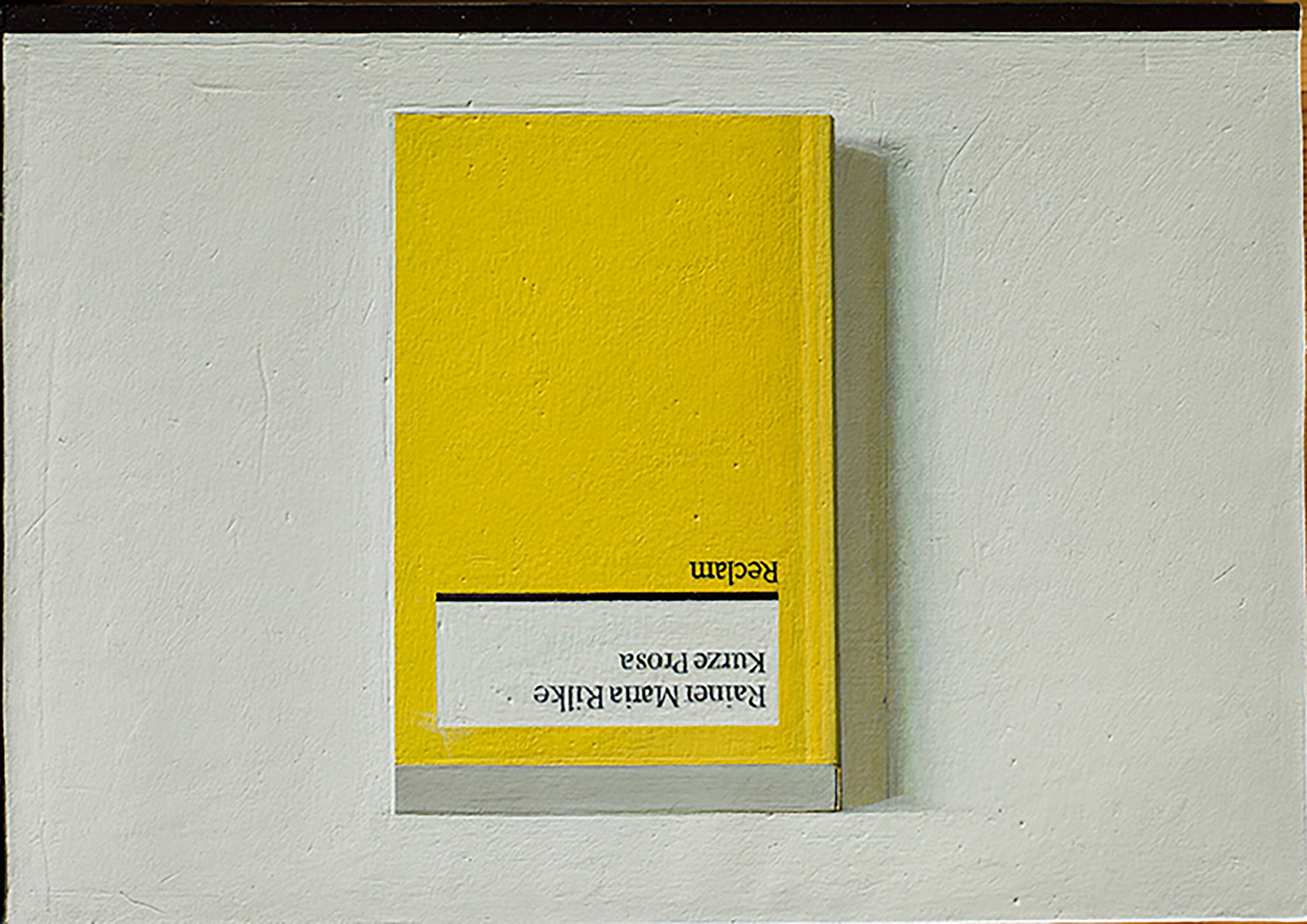

Rainer Maria Rilke’s Kurze Prosa

The Austrian poet and novelist Rainer Maria Rilke is best known for his poetry, but began his career writing short prose and fiction; Liu’s Book Painting No. 9 (2015) depicts a collection of this prose. The book is published by Reclam Verlag, a German publishing house known for printing literary classics in their “little yellow book” design. Liu admitted to never having read Rilke, but painted this book for one reason: “I love Balthus.” (Liu pays homage to Balthus’s suggestive images of pubescent girls in his Banned Book series; in Liu’s paintings, we see them reading.) The Polish-French painter Balthus met Rilke—then his mother’s lover—at age eleven, and Rilke would stay in Balthus’s life as a father figure and mentor. Near the end of his life, Rilke wrote a series of letters to Balthus filled with practical advice on being an artist (we republished their correspondence in the ekphrasis title Letters to a Young Painter). Like many of Liu’s other reference points, the connection drawn between Rilke and Balthus asks: As an artist, how should one live?

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 9 (Rainer Maria Rilke, Kurze Prosa, Reclam, 2012), 2015

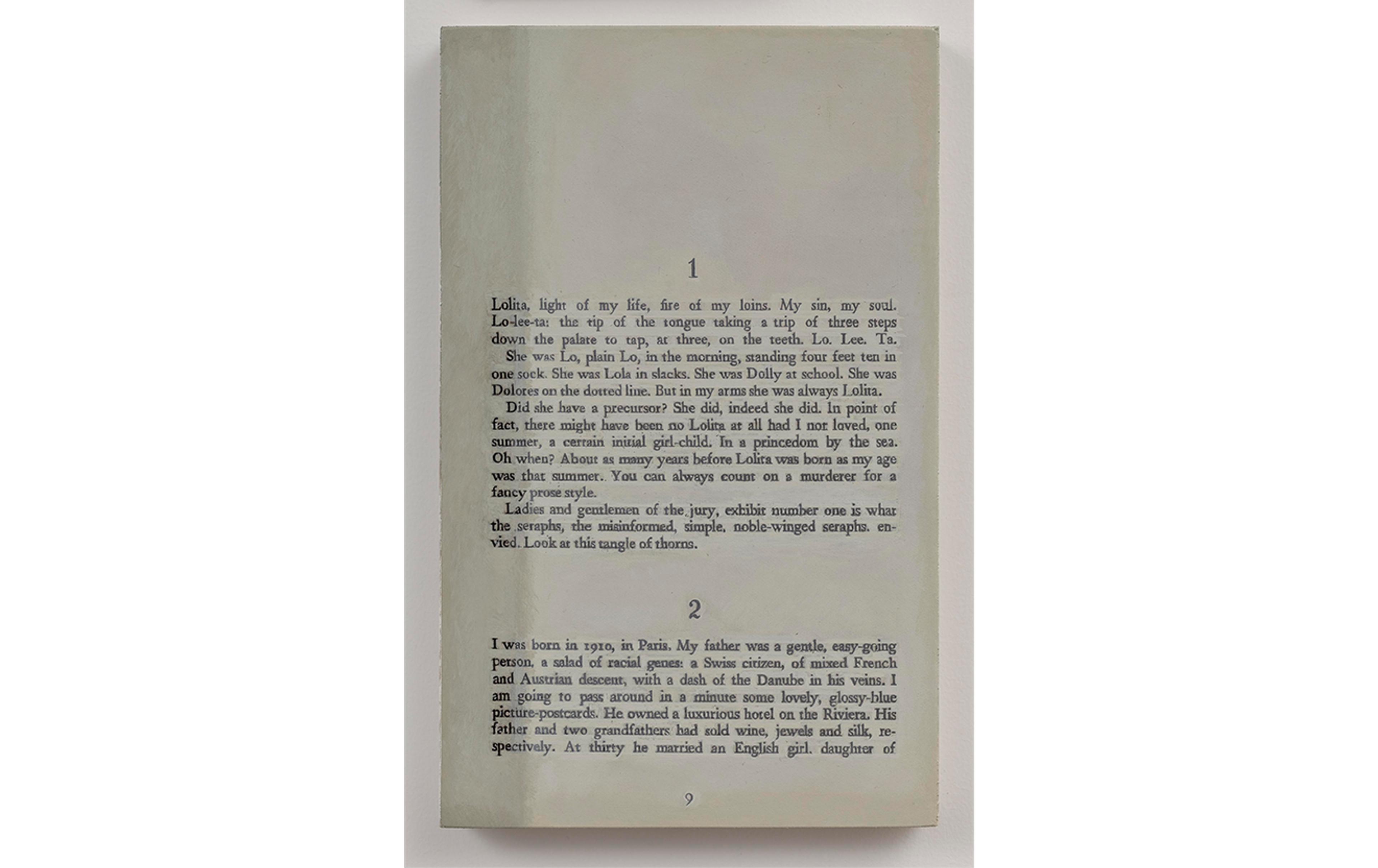

Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita

The figure of the young girl persists in Liu’s paintings; in Book Painting No. 11, No. 12, and No. 15, she takes the form of the famous first lines of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Painting three different editions of the first page of the novel’s text (Vintage International, 1997; Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1959; and The Olympia Press, 1955), each repetition gestures at the complex relationship between image and text. Novels conjure images through words, but in Liu’s painting, the book—a container of words—becomes the image, and the painting becomes the written word. “In this purely visual medium, the written word ascends to prominence as the main subject. Literature is made into an image, or perhaps we should say that the image is made graphic,” writes the poet and critic Zhu Zhu in Liu Ye: The Book Paintings.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 11 (Lolita, Vintage International, 1997, Page 9), 2015

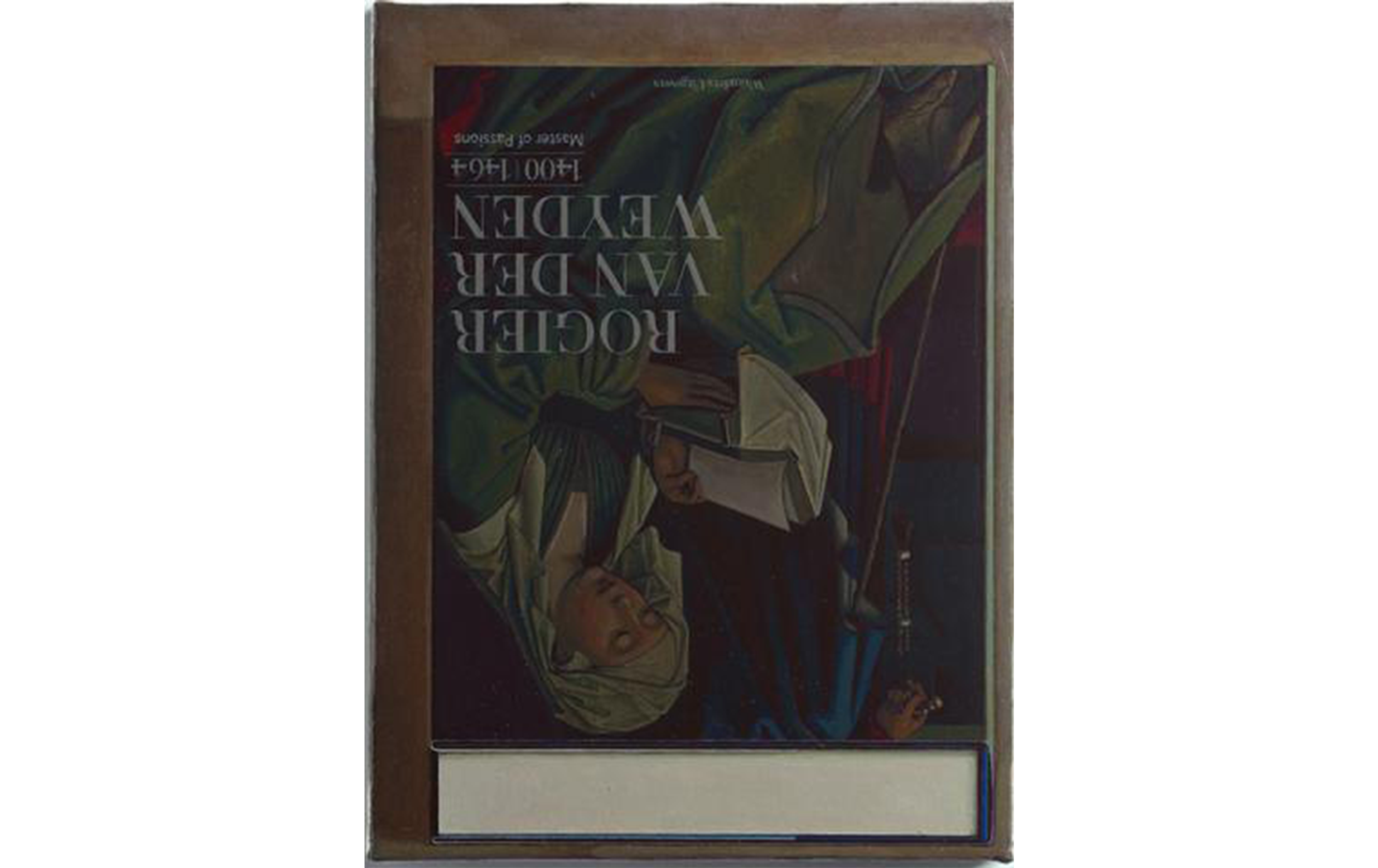

Rogier van der Weyden 1400–1464: Master of Passions

A quick online search reveals that the exhibition catalogue for the monumental 2009 show Rogier van der Weyden: Master of Passions at Museum Leuven, Belgium, painted above, runs anywhere from $1,177.53 to $8,823.98. The now collectible book catalogues the fifteenth-century Flemish master’s religious paintings, altarpieces, portraits, and other aspects of Van der Weyden’s large body of work. The cover displays a detail of Van der Weyden’s The Magdalen Reading—a surviving fragment from a larger altarpiece—linking Liu and Balthus to a long history of portraying women characterized as promiscuous in the solemn act of reading. Like Van der Weyden and many early Netherlandish painters, Liu works by slowly building up layers of paint, creating a glaze-like finish.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 14 (Rogier van der Weyden, Waanders Uitgevers, 2009), 2016

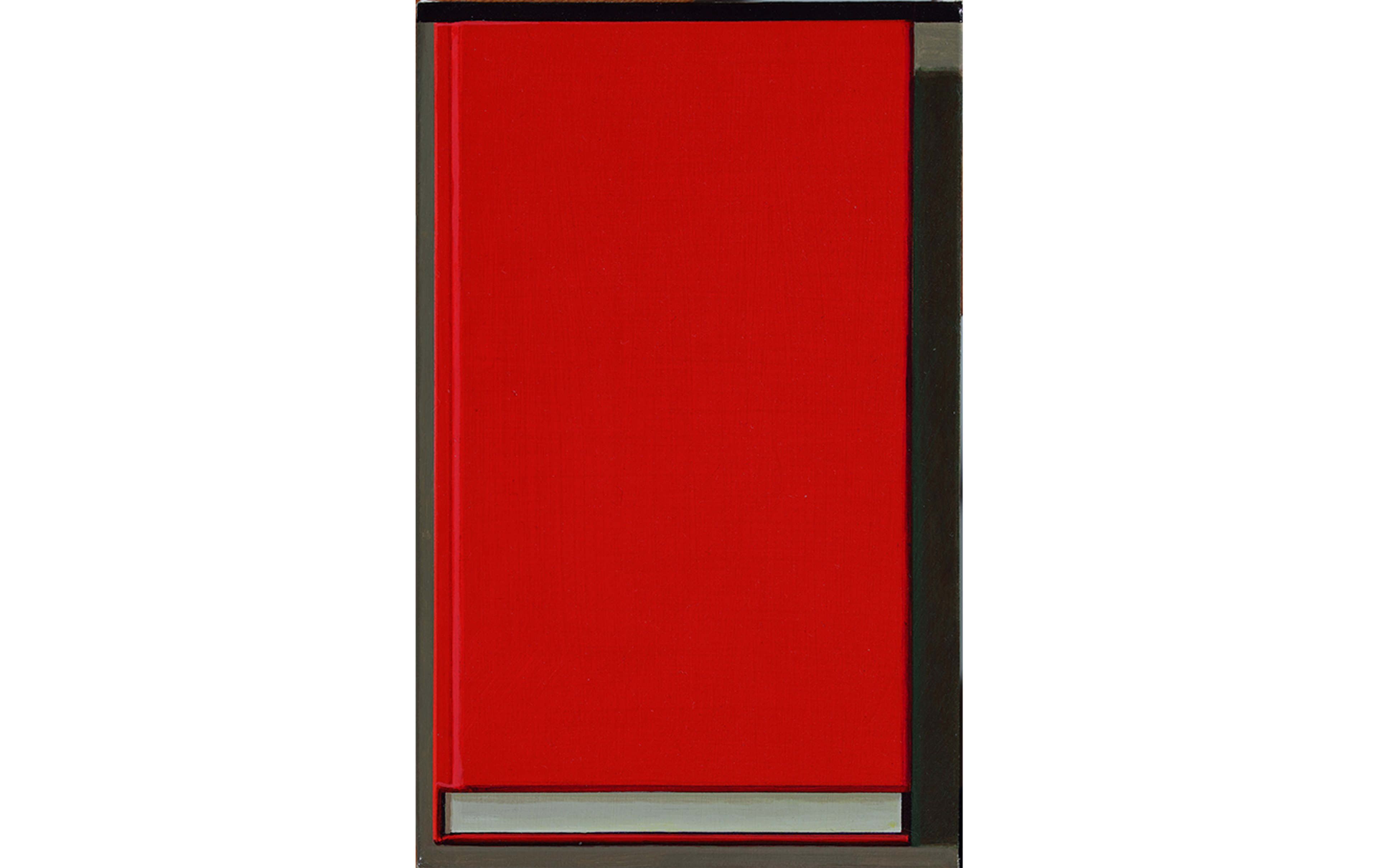

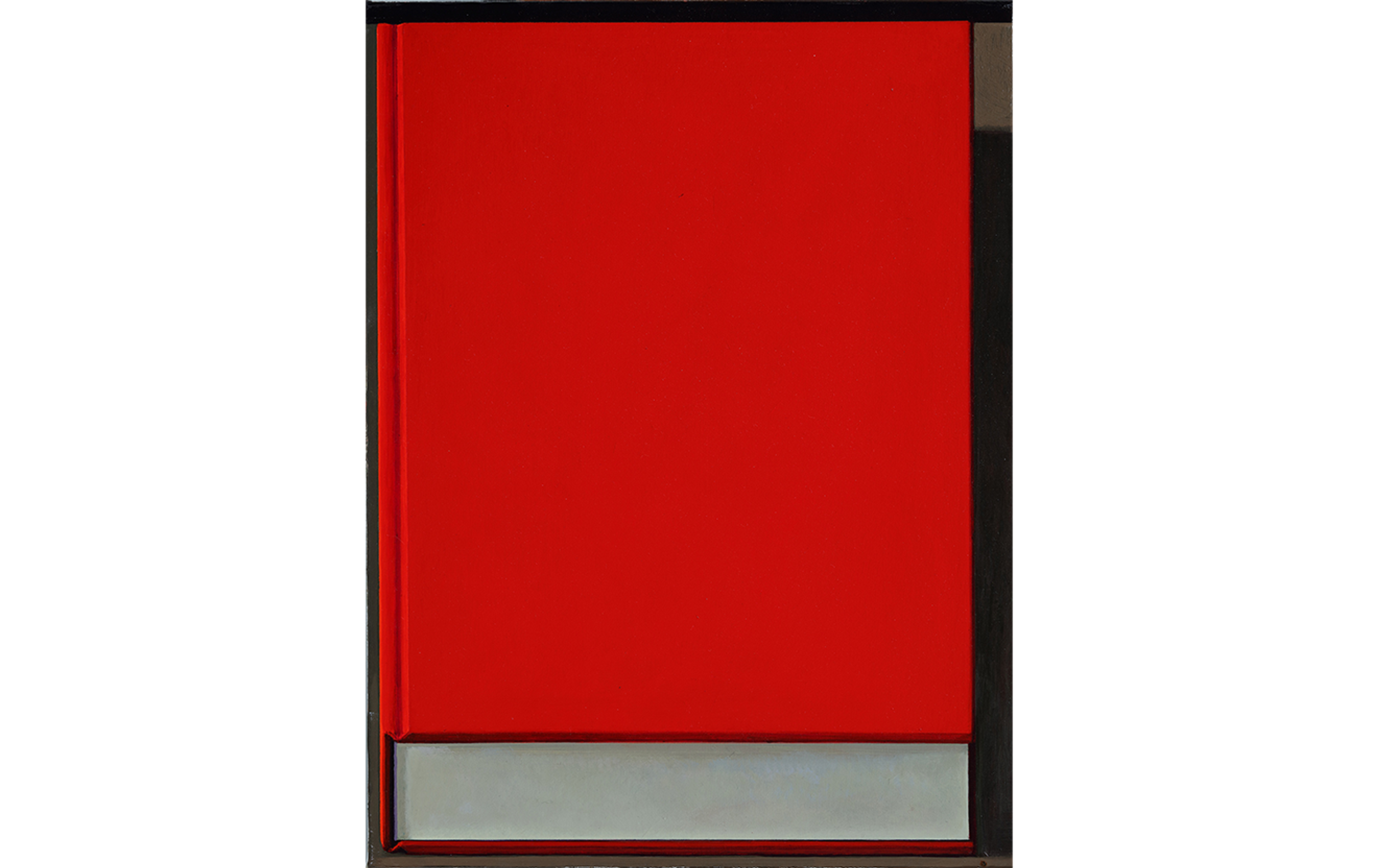

Peter Zumthor’s Architektur denken

Liu is clearly a fan of repeating motifs, and the first edition of Swiss architect Peter Zumthor’s Architektur denken (Thinking Architecture) is just one of many red books he has painted. Zumthor, a Pritzker Prize winner, is known for his subtle designs, his emphasis on the sensuousness of architecture, and his uncompromising approach (he’s loathe to delegate even the choice of a door handle). “I work like an artist and then I make my paintings, and I cannot delegate my paintings,” Zumthor told Dezeen. In the past, critics have connected Liu’s use of the color red to Mao’s Little Red Book, but Liu has denied this, choosing instead to put the emphasis on the form of Zumthor’s book. “Suddenly I realized this,” Liu told Obrist, “the book itself … would be such a beautiful picture.”

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 17 (Peter Zumthor, Architektur denken, Birkhäuser, Basel, 2010), 2017

Barnett Newman: A Catalogue Raisonné

In Book Painting No. 18 (2017), we see yet another red book: a catalogue of Barnett Newman’s oeuvre, including paintings, drawings, sculptures, graphics, an architectural model, and more. The Ab Ex giant, like Liu, was an avid reader, and the book includes an inventory of his personal library. Liu has previously cited Newman as an important inspiration, and Liu’s painting She Isn’t Afraid of Mondrian (1995) is a direct response to Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue series (1966–1970). Interestingly, the title of Newman’s series references Edward Albee’s play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962), which itself references the song featured in Disney’s Three Little Pigs (1933), “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” (1933) by Frank Churchill, linking Liu to an ongoing cultural call-and-response.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 18 (Barnett Newman. A Catalogue Raisonné, The Barnett Newman Foundation, New York; Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2004), 2017

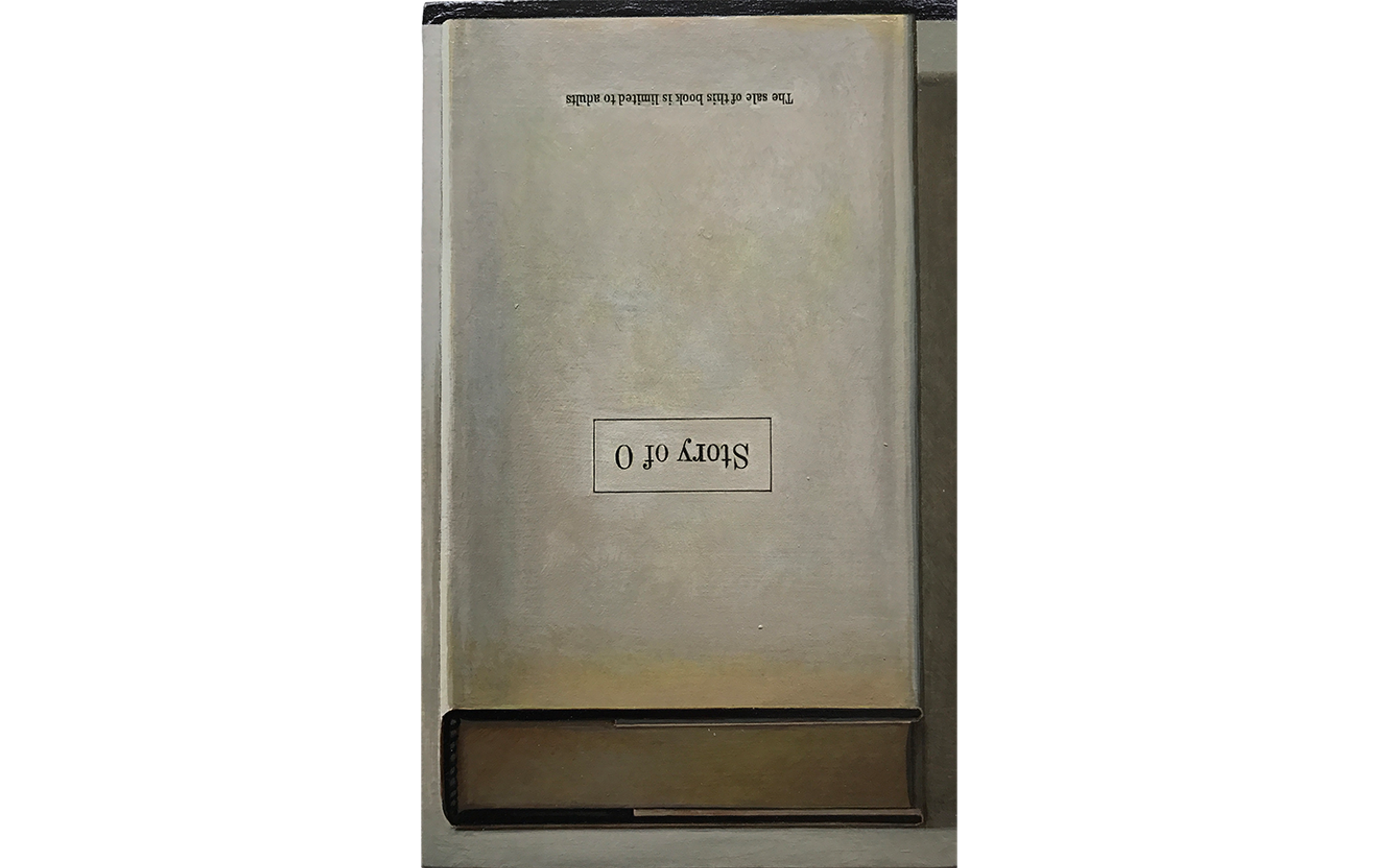

Anne Desclos’s Story of O

Written by the French journalist and novelist Anne Desclos under the pen names Dominique Aury and Pauline Réage, Story of O was a massive success and won the French literature prize Prix des Deux Magots. It tells the tale of a Parisian fashion photographer named O who, at the behest of her lover René, arrives at a château to be trained to serve members of an elite club as a sexual slave and thus explores what it means to consent to the abandonment of one’s free will. At the time of publication in 1954, the book was highly controversial; French authorities charged the publisher with obscenity (unsuccessfully), and Desclos did not admit to being the author of the book until 1994. In line with his Banned Book series, Book Painting No. 19 (2017) alludes to Liu’s interest in social taboos, and generally, in literature deemed illicit and unacceptable.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 19 (Story of O, Grove Press, Inc., New York, 1965), 2017

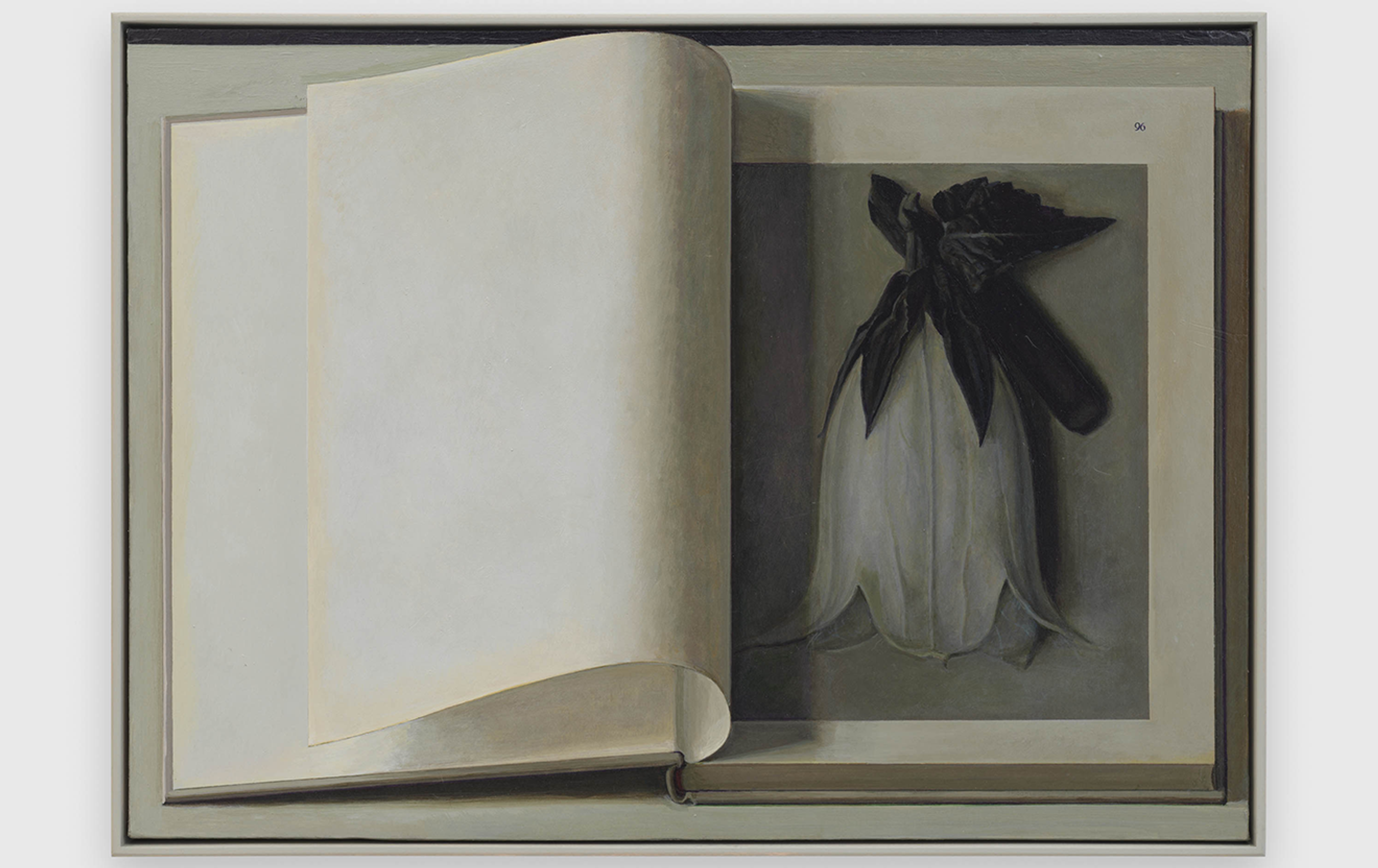

Karl Blossfeldt’s Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature), Wunder in der Natur (Wonders of Nature), and The Complete Published Work

Across a group of paintings, Liu reproduced pages from three of the German photographer and sculptor Karl Blossfeldt’s books: Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature), Wunder in der Natur (Wonders of Nature), and The Complete Published Work. Originally a sculptor who firmly believed in the sculptural qualities of nature, Blossfeldt’s professorship at Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin led him to produce photographs of plant surfaces, which he used as models to teach his students. Using self-modified cameras that magnified images to an unprecedented degree, the precision and beauty of Blossfeldt’s photographs prompted a solo exhibition and the publication of his first monograph, Urformen der Kunst, in 1928. Trained traditionally at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, Liu was instructed to never use photographs to paint. Today, he rejects that notion, instead using photography to reconsider painting, as Blossfeldt did for sculpture: “The contemporary painter should learn from photography,” Liu said.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 20 (Blossfeldt, Urformen der Kunst, Verlag Ernst Wasmuth GmbH, Berlin, 1936), 2017

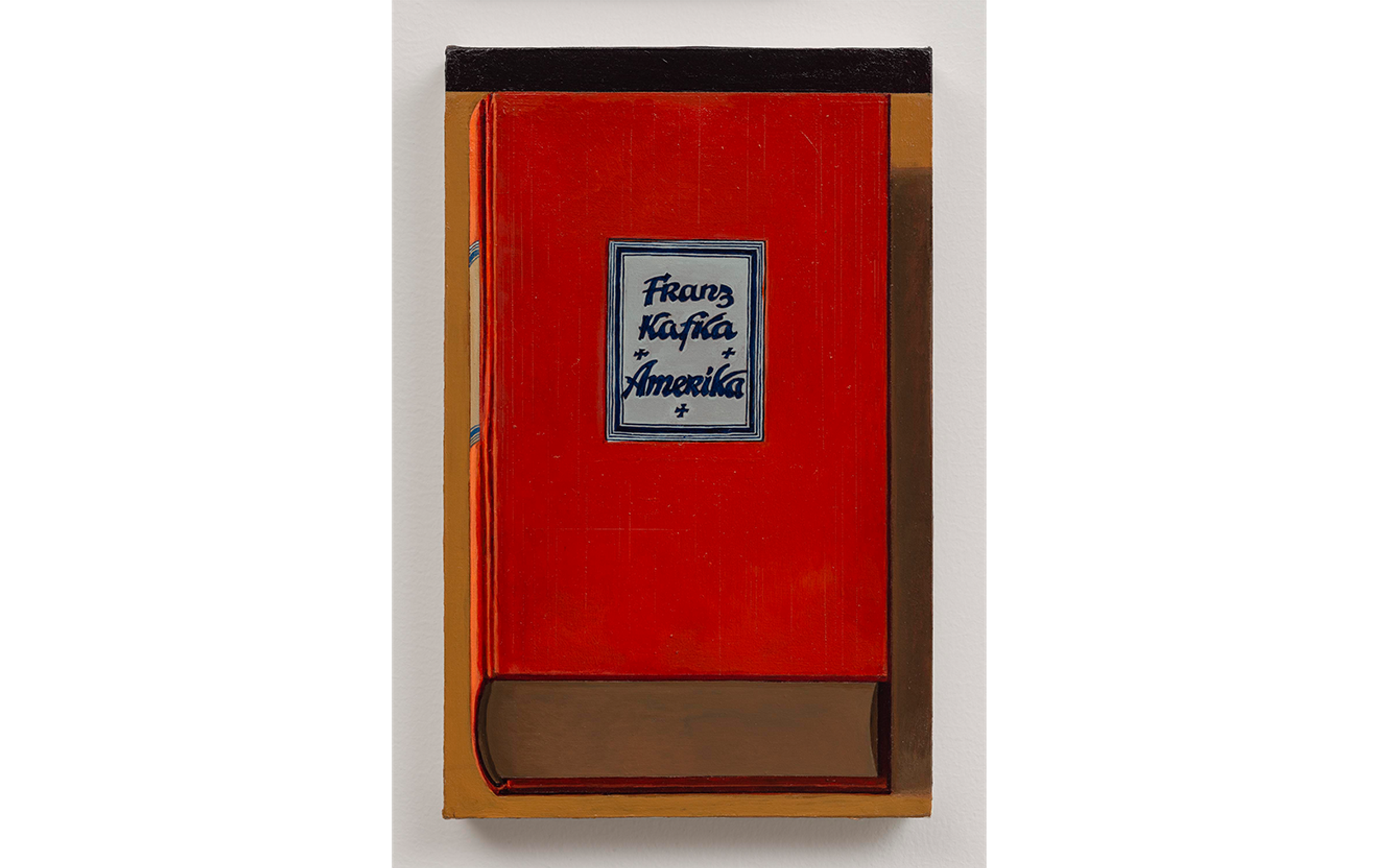

Franz Kafka’s Amerika

Amerika is an unfinished novel by Kafka, which he worked on between 1911 to 1914. As the story goes, in a bout of sadness, Kafka never completed the book, and it was published posthumously in its unfinished state in 1927. The novel follows sixteen-year-old Karl Rossmann and his unlucky attempts to find employment, ending prematurely when Karl applies for work at the Nature Theatre of Oklahoma after seeing an advertisement announcing that “Whoever wants to be an artist should sign up.” In the art world, this book is most closely associated with German artist Martin Kippenberger’s The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s ‘Amerika’ (1994), an installation in which Kippenberger attempts to complete Kafka’s story without collapsing Rossmann’s possible futures into one fixed narrative. The installation is a deliberately confusing aggregate of furniture—chairs, ladders, and desks—with a job interview to be conducted by Kippenberger and his colleagues at each desk. Like Liu’s book paintings, Kippenberger’s citation of Kafka’s novel puts his work in dialogue with the text, allowing him to reconsider both the role of the artist and the artist’s intervention.

Image: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 27 (Franz Kafka, Amerika, Kurt Wolff Verlag, München, 1927), 2019

On Kawara’s One Million Years

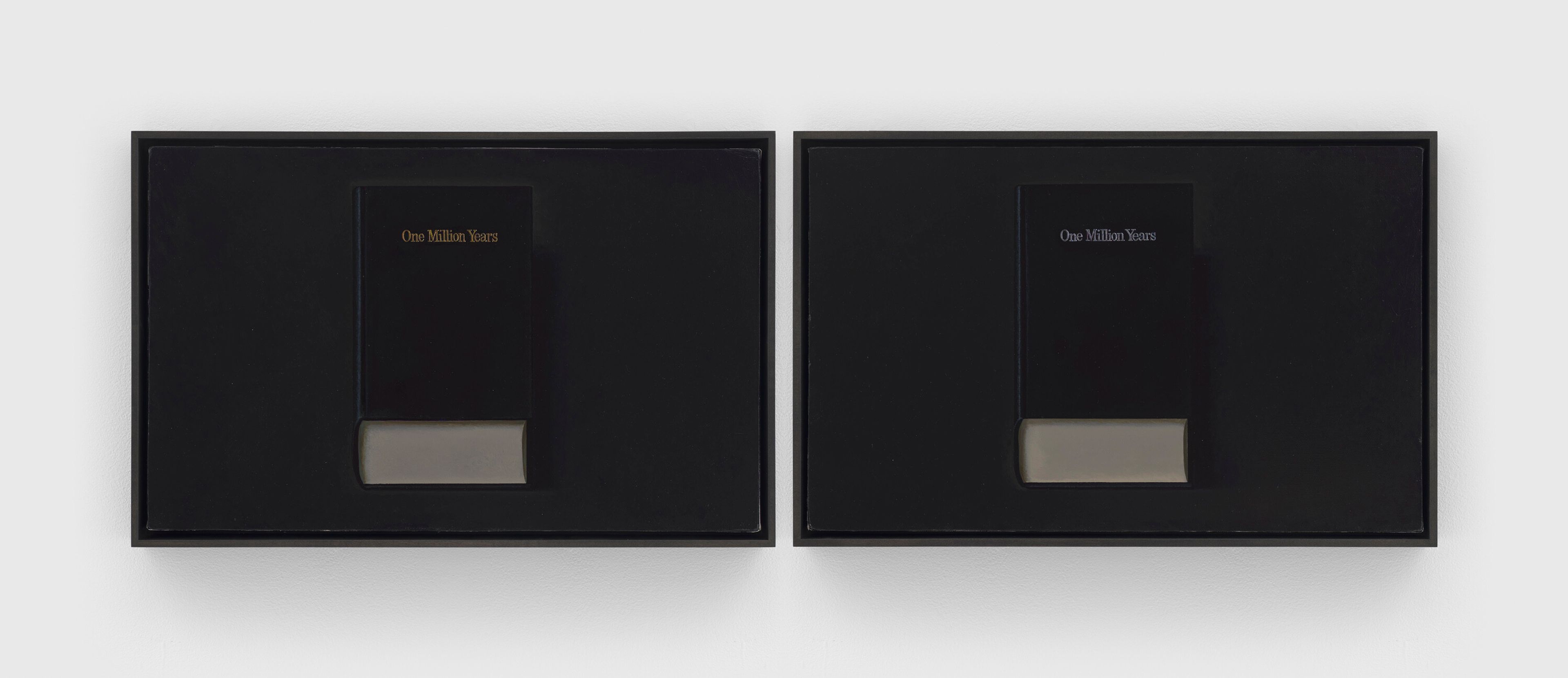

In 1970, the artist On Kawara—known for his “date paintings” and his fixation with time—embarked on what would become a twenty-year journey to create his One Million Years series. Documenting one million years stretching backward from 1970 in one set (One Million Years: Past) and one million years stretching forward in another (One Million Years: Future), Kawara filled each page with five hundred years. To do so, he cut and pasted columns of single digits to typed and photocopied grids of numbers, and eventually, these pages were photocopied to conceal glue and organized into transparent plastic sleeves in leather binders. The pages grew to fill ten binders, with each binder holding two hundred pages. The binders were then published as a two-volume black book, which Liu painted in 2020, echoing Kawara’s concerns with the passage of time.

Image above: Liu Ye, Book Painting No. 28 (On Kawara, One Million Years, two volumes, produced and published in 1999 by Éditions Micheline Szwajcer & Michèle Didier), 2020; header image: Liu Ye, Banned Book No. 1, 2006 (detail)