A timeline of his enduring appeal to artists

December 22, 2019

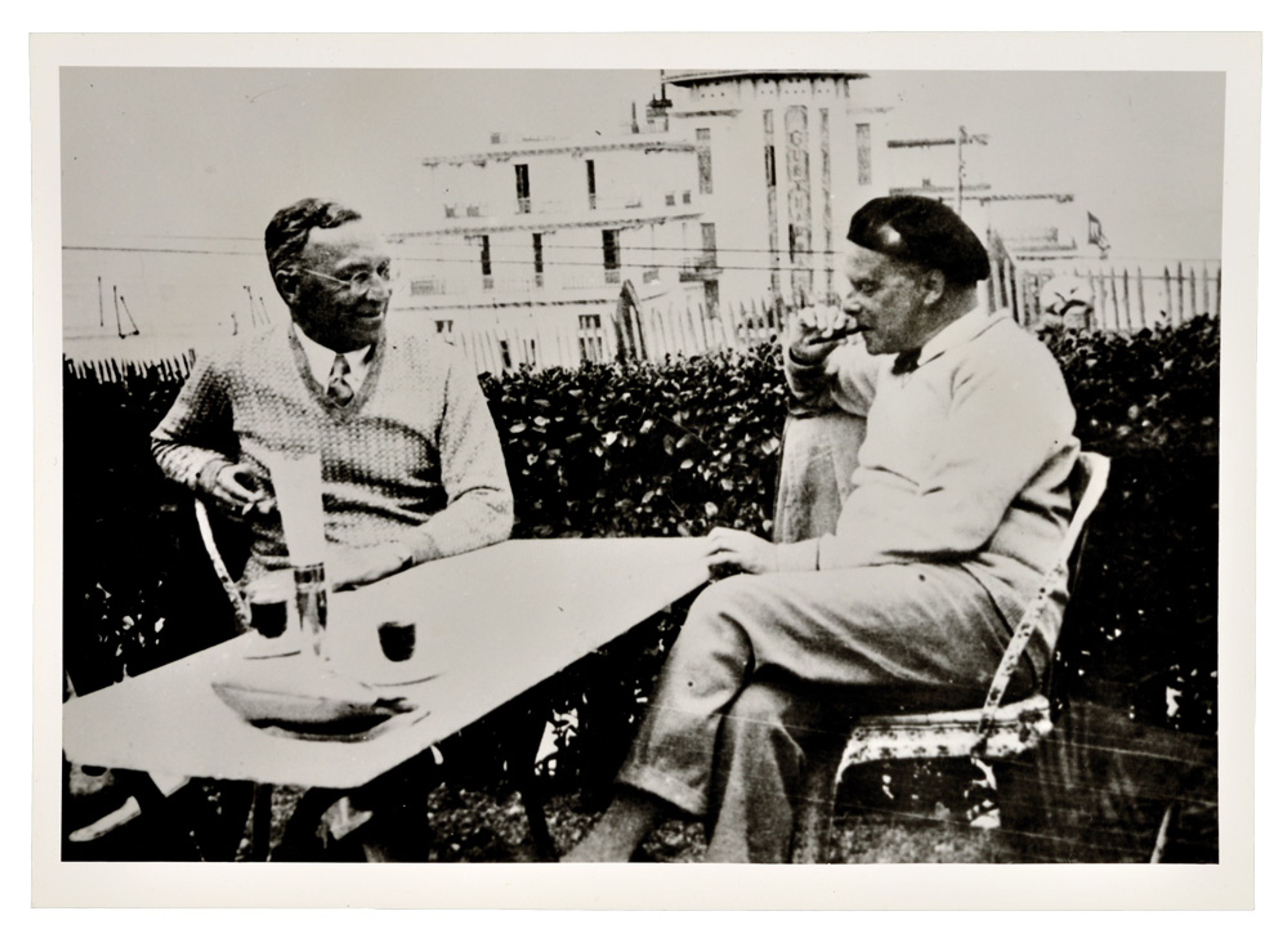

Paul Klee may have been remote in person—some described him, at times, as “unapproachable”—but the territory he opened up through his work continues to affect other artists today, generations after his death in 1940.

“Nothing is more astonishing to the student of Klee than his extraordinary variety,” Alfred Barr, the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, wrote in 1941. “In quality of imagination also he can hold his own with Picasso.” Klee’s energetic experimentation with forms and materials has proved influential for artists from Anni Albers and Joan Miró in the 1920s to Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, and living artists such as Etel Adnan, Michaela Flatley, and Richard Tuttle. Clement Greenberg’s famous observation of 1957—“Almost everybody, whether aware or not, was learning from Klee”—still holds true.

The ’20s: Albers, Miró, Calder

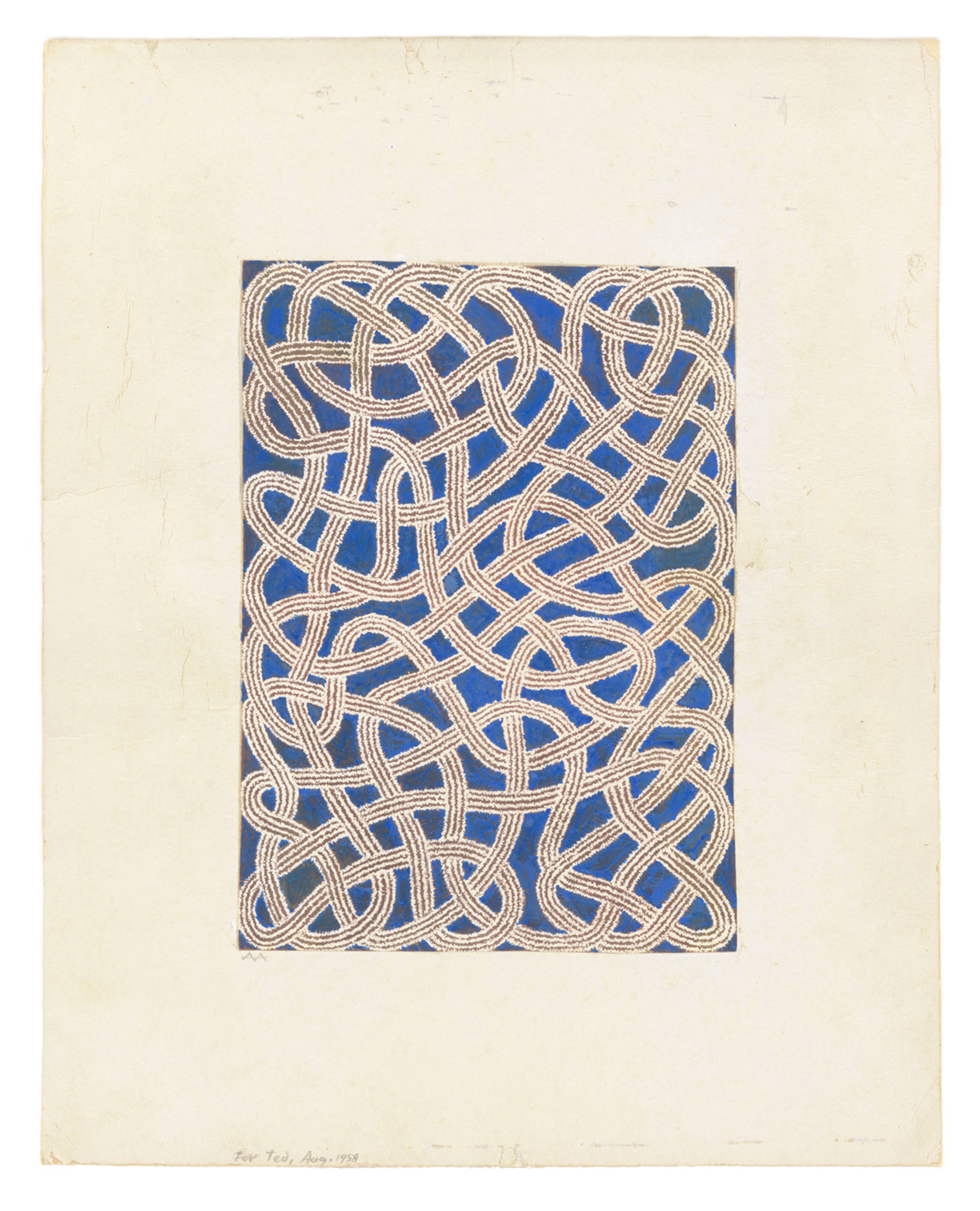

During the 1920s, Klee’s unique use of line—he is said to have called it his “most treasured possession”—inspired his contemporaries both formally and conceptually. A student in the Bauhaus weaving workshop when Klee began teaching Theory of Design there, in 1927, the young Anni Albers transformed her teacher’s instruction to “take a line for a walk” into physical form using thread—an approach that propelled her whole career as an artist.

“I was trying to build something out of dots, out of lines,” she later reflected, “out of a structure built of those elemental elements and not the transposition into an idea.”

Among Albers’s notes is her translation into English of a lecture Klee gave in 1924 titled “On Modern Art”—a text she had hoped to have published, as she later wrote in a letter to the German art historian Charlotte Weidler, to “give me a feeling of having said at last in some way THANK YOU to Klee” (emphasis hers).

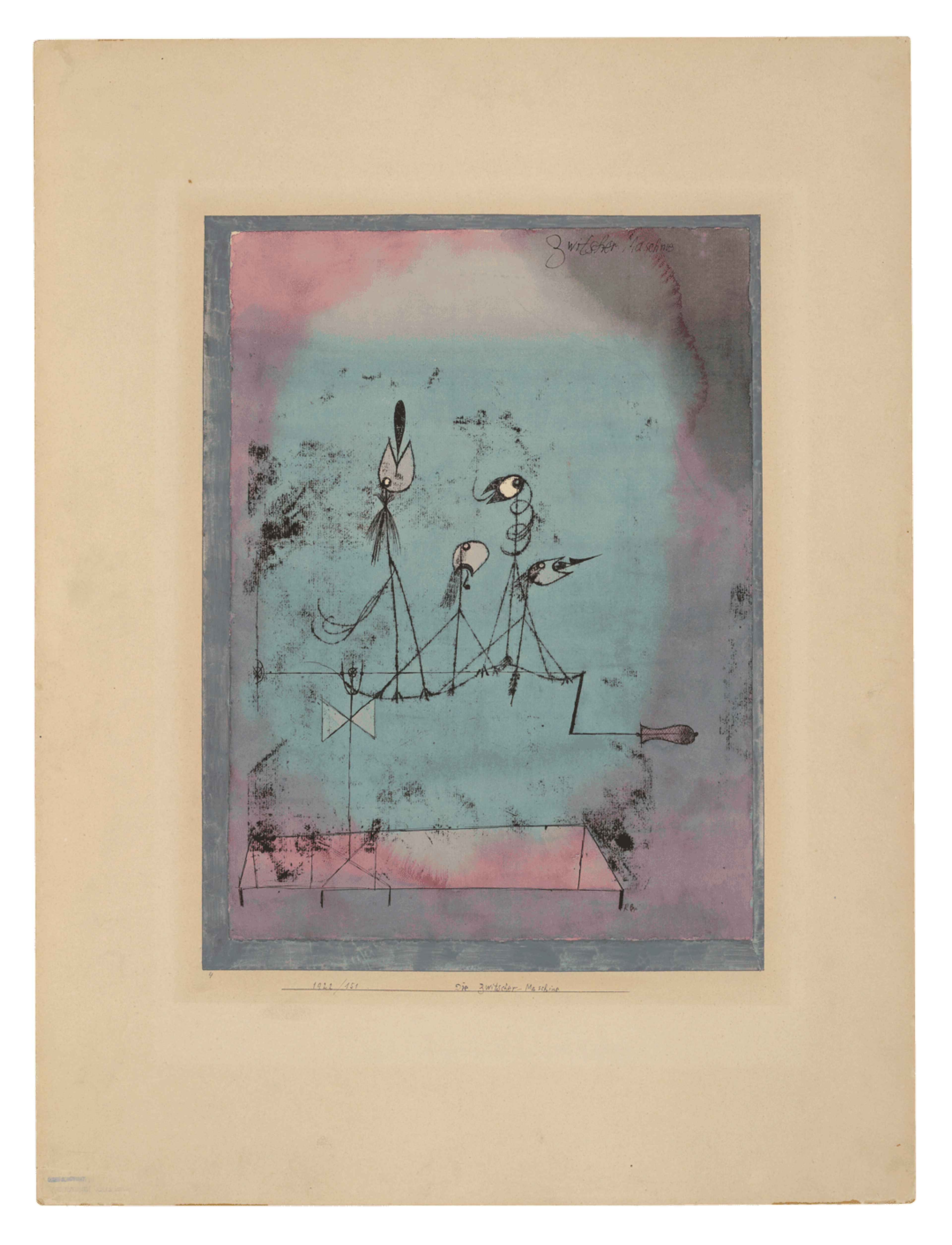

While the German Bauhaus emphasized rational solutions in the aftermath of the war, Klee’s work also appealed to the surrealist movement with which he was partly aligned, and that sought to reveal the “superior reality” of the subconscious mind. In particular, the “pictorial poetry” of Klee’s work, in which line can have a distinct calligraphic quality within a composition, was a revelation to artists seeking to convey the unconscious.

In works such as III Ich bin gesandt einen Alb zu Nehmen von der Menschheit (III I am sent to relieve mankind of a nightmare) (1918) and Die Zwitscher-Maschine (The twittering machine) (1922), Klee enacted his famous statement, made in a 1920 essay titled “Creative Confession,” that “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” In Klee’s work, other artists found a realm of abstraction between the verbal and the visual; his fitful, organic handling appeared to directly inscribe a train of thought, and with a unique lyricism that persisted throughout his oeuvre.

The influence of Klee’s line and his tendency to detach forms from a definitive ground is clear, for example, in the “peinture-poésie”or “painting-poetry” works of the 1920s by Joan Miró, who frequently sought to give expression to memory, and made no secret of the importance the older artist had for him (he likely first encountered Klee’s work in around 1922). “Seeing Miró in light of Klee,“ Elizabeth Hutton Turner writes, “was to witness how Miro had gained entry to an autonomous sphere of abstraction and the unconscious via Klee’s seemingly boundless atmosphere of color and running lines.” Miró later said, “My encounter with Klee’s work was the most important event in my life.”

It may have been through his close friend Miró (whom he met in Paris in 1928), that the sculptor Alexander Calder became one of the earliest American artists to have been affected by Klee. Calder’s “mobiles,” in which bent wire creates lines in space that are weighted and lightly choreographed by attached steel shapes, seem indebted to the structural rhythm of Klee’s compositions, which are similarly “suspended” in two dimensions, and which can appear imbued with movement.