In Focus

Kerry James Marshall

Africa Revisited

The first painting of the cycle, Cove presents what appears at first to be an unremarkable scene in which several oarsmen loiter around three beached canoes, waiting to embark on their next journey. Apart from one reclining figure—an art-historical trope often used as a signifier of leisure—who lounges in the front canoe, the rest of the men look out towards the distance. There, chained captives are being led single file toward the boats.

The rowers are a de facto audience of complicity, one into which the viewer is necessarily incorporated, observing men of similar attire being herded toward a vastly different fate.

Standing just over a foot taller than the other two identically sized paintings, Outbound shows a canoe energetically surging forward, en route to deliver soon-to-be slaves to an unseen vessel.

The seagulls swoop and dive in different directions, lending the scene an ominous sense of momentum. A standing courrier wearing modern-looking shorts (the pattern is based on a 1990s necktie from the artist’s collection of textiles in his studio) effortlessly balances a figure bound with braided grasses on top of his head. Note how the figure is drastically foreshortened, with only his outstretched palms and the soles of his feet immediately legible. A captive child sits above him, gazing plaintively at the viewer; meanwhile, a seagull catches a ride atop the child’s head.

Kerry James Marshall, Haul, 2025 (detail)

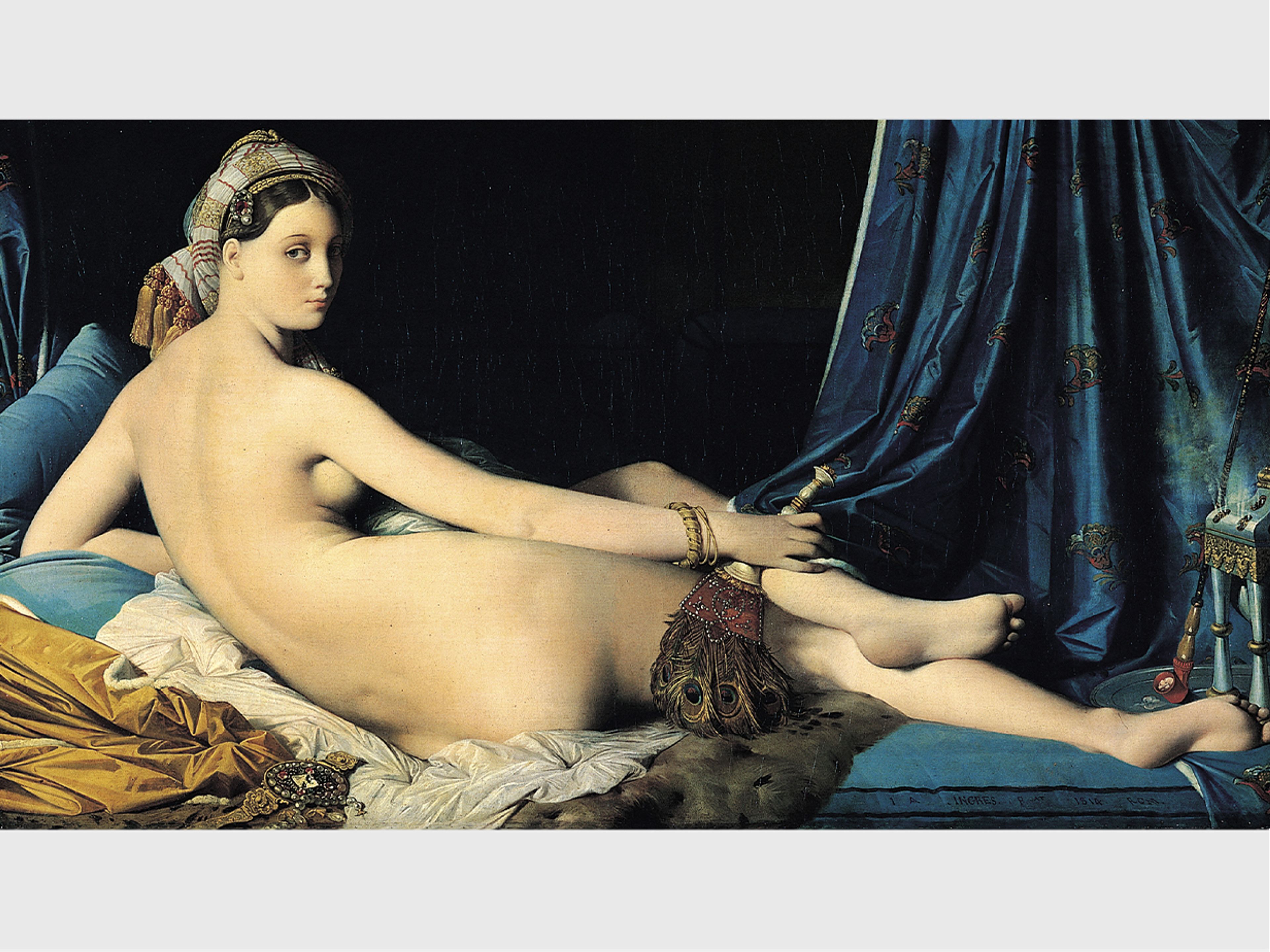

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814. Collection of the Louvre, Paris

Kerry James Marshall, Haul, 2025 (detail)

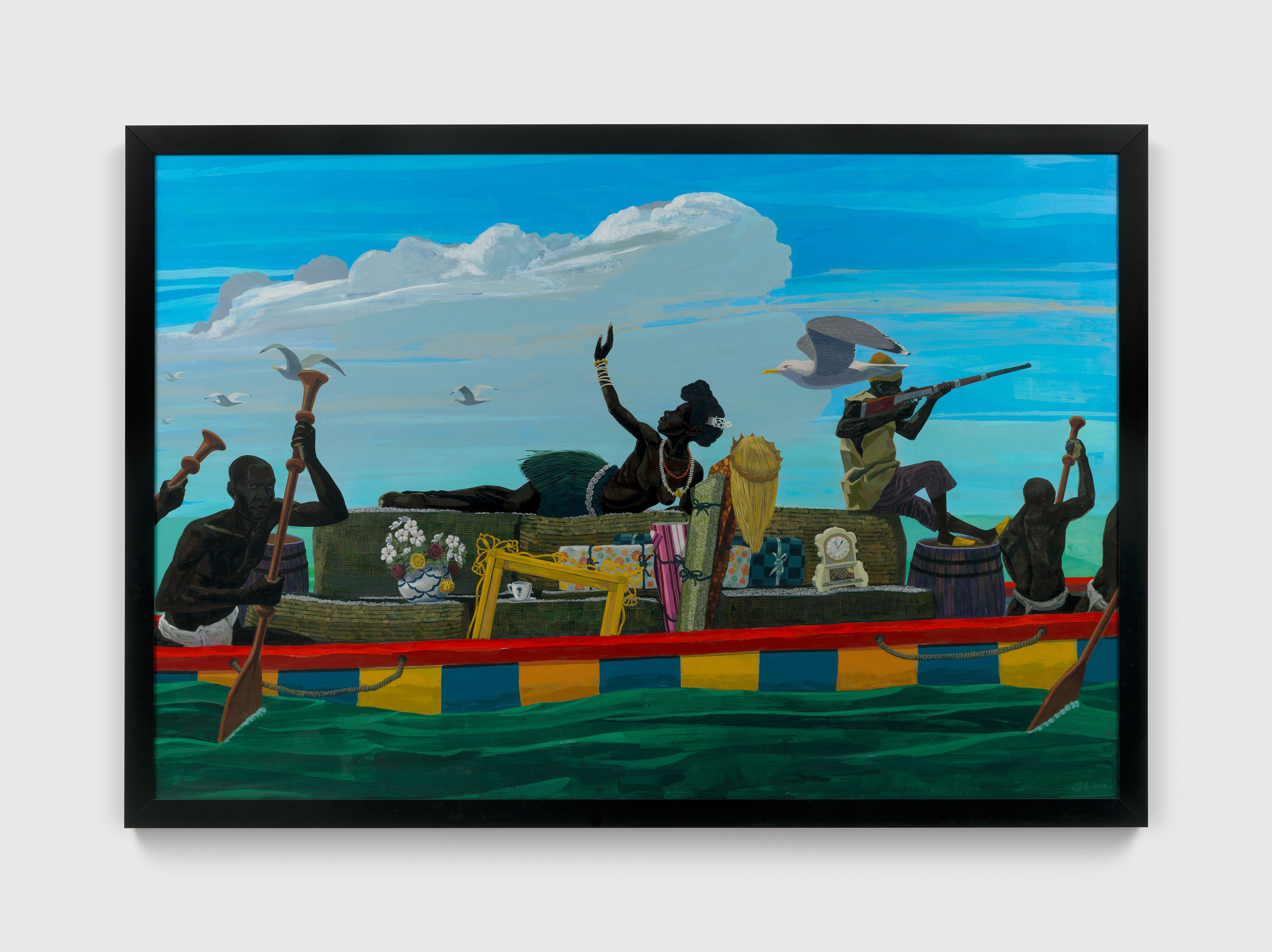

Haul, the last painting of the cycle, pictures the return from a trade. A canoe comes back to shore, laden with goods received: kegs of rum, guns, and great baskets of cowrie shells—all known to have been traded within Africa in those years—as well as a Victorian teacup, a mantel clock, and other such European prizes. A female figure bedecked in cowries—Marshall’s own La Grande Odalisque—reclines in the center of the canvas with her hand raised to the sky to block the sun. Idling seagulls dot the composition and placid sea, as though to suggest that the boat is moving at a leisurely pace; in fact, upon closer inspection, four rowers are required to move the canoe’s tremendous bounty through the water. The scene features a handful of anachronistic details, including objects in modern gift wrap, a blonde wig wearing a crown, and the 1970s-inflected outfit of a gunner who keeps watch over the horizon. On the rifle plate, Marshall has affixed his own monogram, as if to further stamp the artist’s presence and authorial subjectivity.

Kerry James Marshall, Abduction of Olaudah and his sister, 2023 (detail)

Kerry James Marshall, Abduction of Olaudah and his sister, 2023 (detail)

In Abduction of Olaudah and his sister, Marshall imagines the abduction of Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745–1797) and his sister from their village of Essaka, located in present-day Nigeria, a real-life event that took place when Equiano was around the age of eleven. After being transported to the Caribbean, where he was sold into slavery in the Americas, Equiano eventually gained his freedom in 1766. He became a well-known writer and abolitionist in London, where he settled as a freedman. Equiano went on to detail his abduction in his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, which became a key text in England’s burgeoning abolitionist movement, of which he was a leading figure; the book remains an important primary source from this period. In the painting, the kidnapping is partially obscured by foliage—“a matrix placed to sew us into the view, a veil set to heighten care in observation,” as Darby English notes in the exhibition catalogue. The lush surroundings, with birds and monkeys roaming freely through the branches, stand in direct contrast to the nefarious act happening within. The perpetrators are dressed anachronistically in modern clothing, suggesting the continued occurrence of such events. Their hands are clamped over the children’s mouths, literally silencing them. In the center of the composition, a shirtless man stands wielding a rifle on which Marshall has included an elaborate ivory carving that replicates the titular figure from Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. Just above, Marshall has affixed his own monogram to the gun’s medallion, to again make visible his authorial presence and subjectivity. As English suggests, the artist does this in order to “to fuse his action with the slavers’ grandiose shows of force, which at once signal the fragility of their operations and flex the muscle reinforcing those operations against threats from similarly opportunistic competitors.”

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (London Bridge), 2017. Collection of Tate London

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (London Bridge), 2017 (detail)

The figure of Olaudah Equiano first appeared in Marshall’s oeuvre in the 2017 painting Untitled (London Bridge), which depicts the London Bridge after it was reconstituted in Lake Havasu City, Arizona, moved there brick-by-brick as a novelty tourist attraction in 1971. In this painting—a rare instance of the artist foregrounding white figures within a composition—a Black man dressed in British paraphernalia wears a sandwich board advertising “Olaudah’s Fish & Chips,” which features a portrait of Equiano based on the frontispiece of his autobiography. In embedding this reference within the painting, Marshall draws a parallel between the Bridge and Equiano, both displaced from their original context and reabsorbed into the cultural imagination.

Ruth Williams Khama and Seretse Khama, pictured in 1949.

The National Assembly building in Gaborone, Botswana, with its recognizable arches.

Kerry James Marshall, White Queens of Africa: Ruth, 2025 (detail)

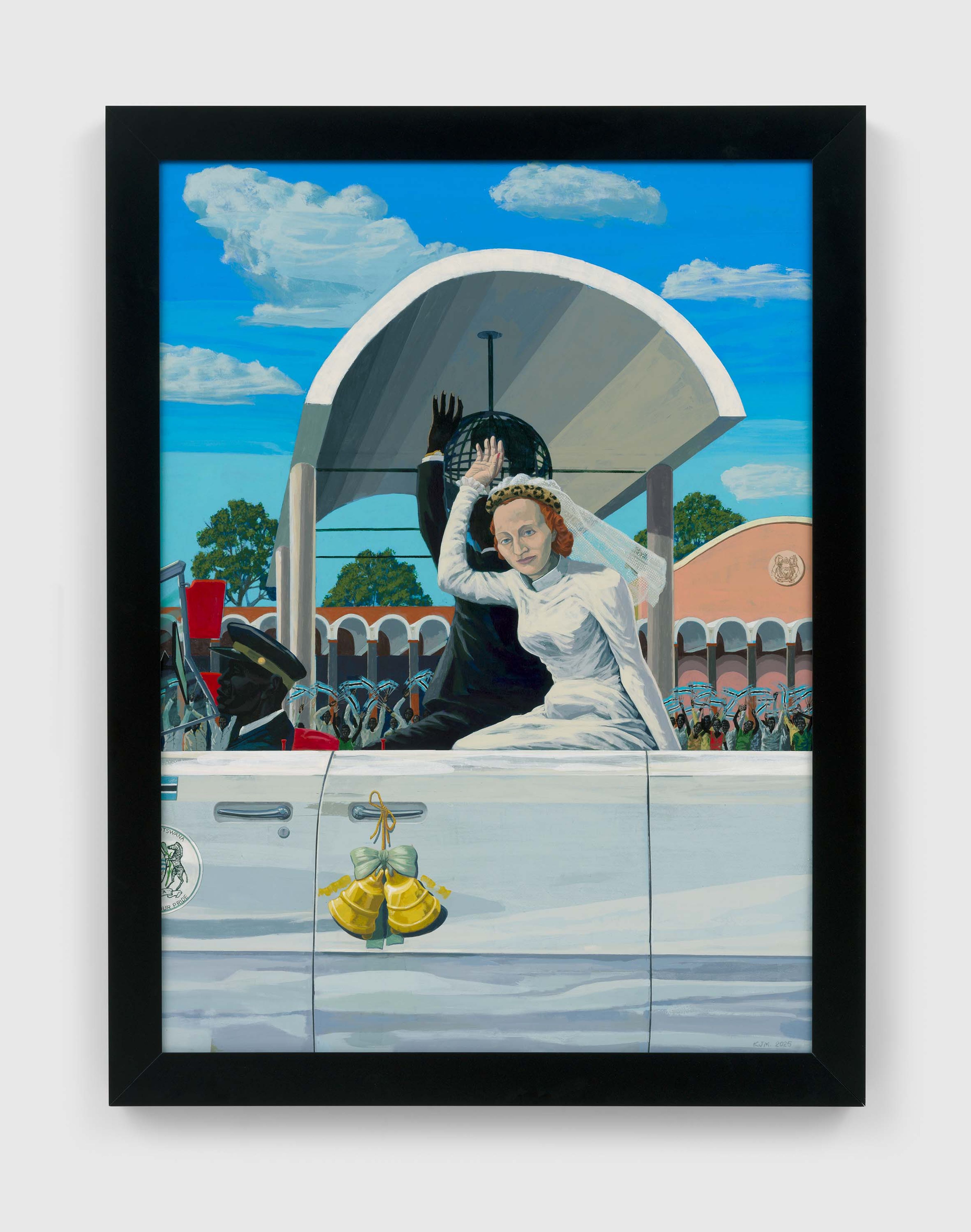

One of two White Queens of Africa paintings on view, Ruth is the imagined wedding portrait of Ruth Williams (1923–2002), a white Englishwoman who upon her 1948 marriage to Seretse Khama (1921–1980), a prince of the Bamangwato people in a then-British protectorate called Bechuanaland (now known as Botswana), became the First Lady of Botswana from 1966 to 1980. Khama was educated in the UK, where he met Williams, who was working as an insurance clerk, and the two quickly fell in love. Their marriage caused an international uproar. The white-minority government of neighboring apartheid-era South Africa opposed the interracial union and asked the UK to intervene. Likewise, some Bamangwato tribal elders were dismayed their prince and heir apparent chose an outsider (though Khama was able to allay their concerns). In response to pressure from South Africa—at the time still a member of the British Commonwealth—the UK held Khama in exile in England for nearly a decade. When he eventually returned, Khama led his country’s drive for independence, becoming prime minister in 1965 and being elected as Botswana’s first president one year later. Khama was a transformative leader, ushering the country into a period of stability and prosperity, while Williams established herself as a respected and influential figure. In the artist’s rendition, Williams rides through the capital city, Gaborone, atop a white convertible that bears Botswana’s coat of arms. The recognizable arches of the country’s National Assembly, the seat of its democratic government, are visible in the background. Waving to the assembled crowds, Williams is dressed in an English-style bridal gown, which is contrasted by a leopard headpiece. She gazes directly at the viewer, her body partially obscuring her new husband, who faces away. Khama, also dressed in Western clothing, greets well-wishers, who wave the light blue, black, and white of Botswana’s new flag. As elsewhere in this series, this composition is replete with anachronisms—in this case, to underscore the inherent symbolism, and maybe even irony, of Williams’s position. In real life, Williams and Khama were so beset by scandal that they married quietly in a register office in London; the Botswana coat of arms and flag were not actually adopted until the country gained independence eighteen years later. And in choosing to feature Williams—as opposed to her husband, a notable figure in African history—Marshall shifts focus to the presence of “the white queen” during the early days of postcolonialism in Africa.

Colette Hubert Senghor and Léopold Sédar Senghor, pictured in 1961.

The presidential palace in Dakar, Senegal.

Kerry James Marshall, White Queens of Africa: Colette, 2025 (detail)

White Queens of Africa: Colette imagines the wedding portrait of Colette Hubert (1925–2019), a Frenchwoman who served as the First Lady of Senegal from 1960 to 1980. In 1957, in a small ceremony in France, she wed the Senegalese poet, intellectual, and politician Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906–2001), a staunch advocate of civil liberties in France’s territories in Africa at the time. Notably, Senghor was one of the primary theoreticians of Négritude, a movement among francophone writers and thinkers that advocated for the affirmation of Black cultural heritage and identity, both in colonized Africa and the European diaspora, fighting against the threat of assimilation. Just three years after his wedding to Hubert, Senghor became the first president of the newly independent Senegal. Senghor referred to Hubert as the love of his life; she was both a muse for his literary endeavors and a ballast in his political life. In the painting, Hubert, dressed in full Western bridal regalia, walks alone down a makeshift aisle leading out of the presidential palace in Dakar, led by a single flower girl who gazes out at the viewer. Hubert is veiled by the shadow of a canopy made from French and Senegalese flags that are literally stitched together, held up by attendants wearing green and yellow outfits adorned with Senghor’s face. Of course, Marshall has put Hubert in front of a building that in 1957 she did not yet live in, surrounded by the green, yellow, and red tricolor that had not yet been adopted, in a country where her wedding did not take place. And, as with Ruth Williams, Marshall puts the focus on her presence during this early postcolonial era.

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy of Art, London, 2025

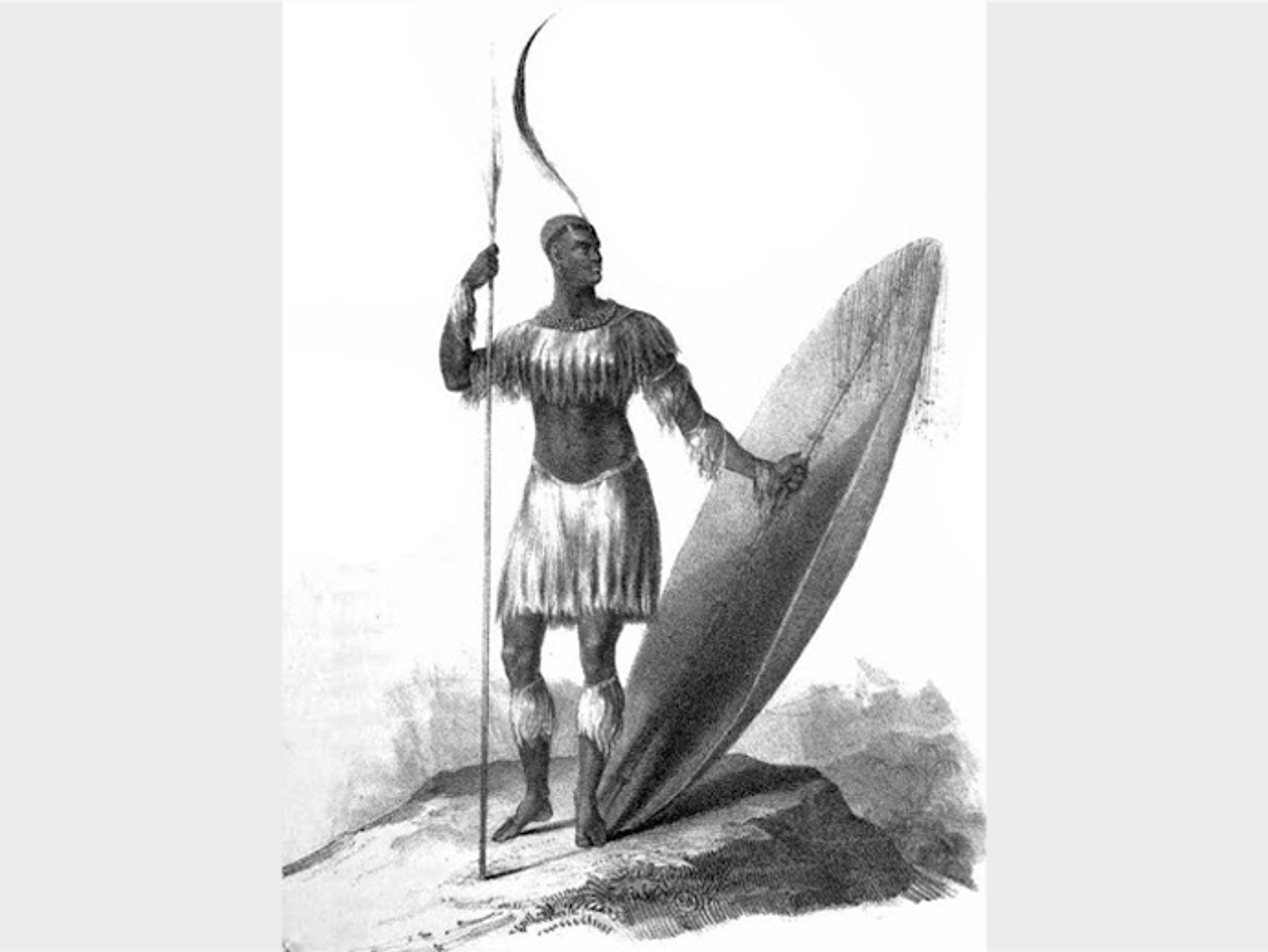

Drawing of King Shaka, 1824, attributed to James Saunders King, the only known depiction of him from his lifetime.

In this painting, Marshall imagines the assassination of King Shaka (c. 1787–1828), the monarch of the Zulu Kingdom in Southern Africa from 1816 until his murder in 1828. A vaunted warrior, Shaka succeeded in consolidating a number of rival clans into a formidable kingdom during his reign. Following a period of increasingly erratic behavior and tyrannical rule in the wake of his mother’s death in 1827, Shaka was assassinated by his half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana. His killing was framed as the half-brothers’ attempt to preserve the tribe’s rapidly dwindling dominance and protect its people from a rampaging, grief-stricken king. Over time, King Shaka has been appropriated into cultural discourse and depicted in a range of oversimplified guises, from the stereotypical “noble savage” to a mythical figure. Marshall’s painting captures the critical moment of Shaka’s assassination, the actual details of which are absent from the historical record. (And there is only one known depiction of Shaka from his lifetime, a drawing seen at right.) Shaka gazes over his lands from the edge of a precipice, observing a line of covered wagons approaching the huts of a Zulu village. Entirely focused on enemies from the outside, he does not notice the assailants approaching at his back. The figure on the left brandishes an iklwa, a short spear with a sword-like tip. (One of Shaka’s key military innovations was to outfit his warriors with iklwa and large cowhide shields, a more effective, close-range tactic than the long throwing spears previously favored.) Seconds from striking the fatal blow—and probably changing the course of African history with a single act of fratricide—the figures advance silently while Shaka’s own iklwa and shield rest against a tree beside him. As English notes, with works such as Assassination of Shaka, the Zulu, “Marshall extends the series’ mediation on choices strategically framed as betrayals in order to purify a history that never was, never could be pure.”

Kerry James Marshall, Six for one, 2024 (detail)

Jacques-Louis David, The Intervention of the Sabine Women, 1799. Collection of the Louvre Museum, Paris

As his point of departure for this imagined scene, Marshall uses a line found in a European slave trader’s journal (referenced in the artwork’s title): “They used to give 12 men for one horse. Now they only want to give 6.” Indeed, a large horse stands regally in the foreground of the painting, presumably acquired in exchange for six people. A gaggle of attendants fawn over the animal, shielded from the hot sun by a colorful umbrella reminiscent of the parasols prevalent in nineteenth-century depictions of bourgeois leisure. (European horses were not well suited to the climate of West Africa.) Several people dress the horse, braiding its mane and tasseling its hooves, while a small child waits nearby, holding the reins in a basket. By contrast, the oba, or chief, is relegated to the background of the composition, and appears diminutive. Marshall emphasizes the collision of African and European cultures throughout the composition, evident in the activities and appearances of the range of individuals he depicts, as well as the architecture. The space of the painting is grounded by a large rectilinear structure in the background, its thatched roof dotted with chickens and framed on either side by the low trees native to the region. The oba appears on the building’s portico wearing a red cassock, an indicator of the arrival and adoption of Christianity—and a sign of not only Western goods, but also ideology, being imported. Behind him, two large bronze plaques (made by melting down the Portuguese currency paid for slaves) punctuate the façade and feature imagery emblematic of the oba’s power. A leopard and a rifle-wielding sentry patrol the ground in front of him. Throughout this body of work, the artist borrows numerous compositional and perspectival strategies from Renaissance and neoclassical painting—styles that have crucially informed the Western tradition and are noted for their illusionistic treatment of space—and uses them to question the ways in which history is constructed. In the center of the painting, a single female figure dances gleefully, arms outstretched in revelry. Her pose and positioning echo Jacques-Louis David’s The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799), another history painting that depicts the consequences of a mass abduction. To the woman’s left, a cavalcade of drummers and revelers contribute to the festive atmosphere, as do five individuals who hold aloft horns made from carved ivory elephant tusks—rarified and valuable objects they have chosen to keep rather than barter as a sign of respect for the oba. The composition, as with each work in this new series, is placed in a black aluminum artist’s frame, calling attention to its status as art-object and acting as a reminder of the constructed nature, as well as untold complexities, of all historical accounts. Moreover, in debuting this series at London’s Royal Academy, Marshall mounts a direct challenge to the hegemony of the West in constructing and upholding the dominant historical and art-historical narratives, which frequently gloss over any involvement with slavery. Yet, in Six for one, the slave trade is referenced only obliquely, and Marshall instead shifts focus to how its introduction affected African society, pushing it towards a Western idea of modernity. As Darby English elaborates: “Folding slavery into a larger story suggests, not coyly, that we have a larger story. This episode concerns the desires slavery aroused in some Black people. As Marshall says, it opens ‘a more realistic view of what we are willing to do to each other in order to get some stuff.’”

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2025. Photo by David Parry

Kerry James Marshall in his studio, 2020. Photo by Lyndon French

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories Royal Academy of Arts, London

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2025

Select Press for Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2025