Exceptional Works: Marlene Dumas

Magdalena, 1995

Oil on canvas 110 3/8 x 39 1/2 inches 280 x 100 cm

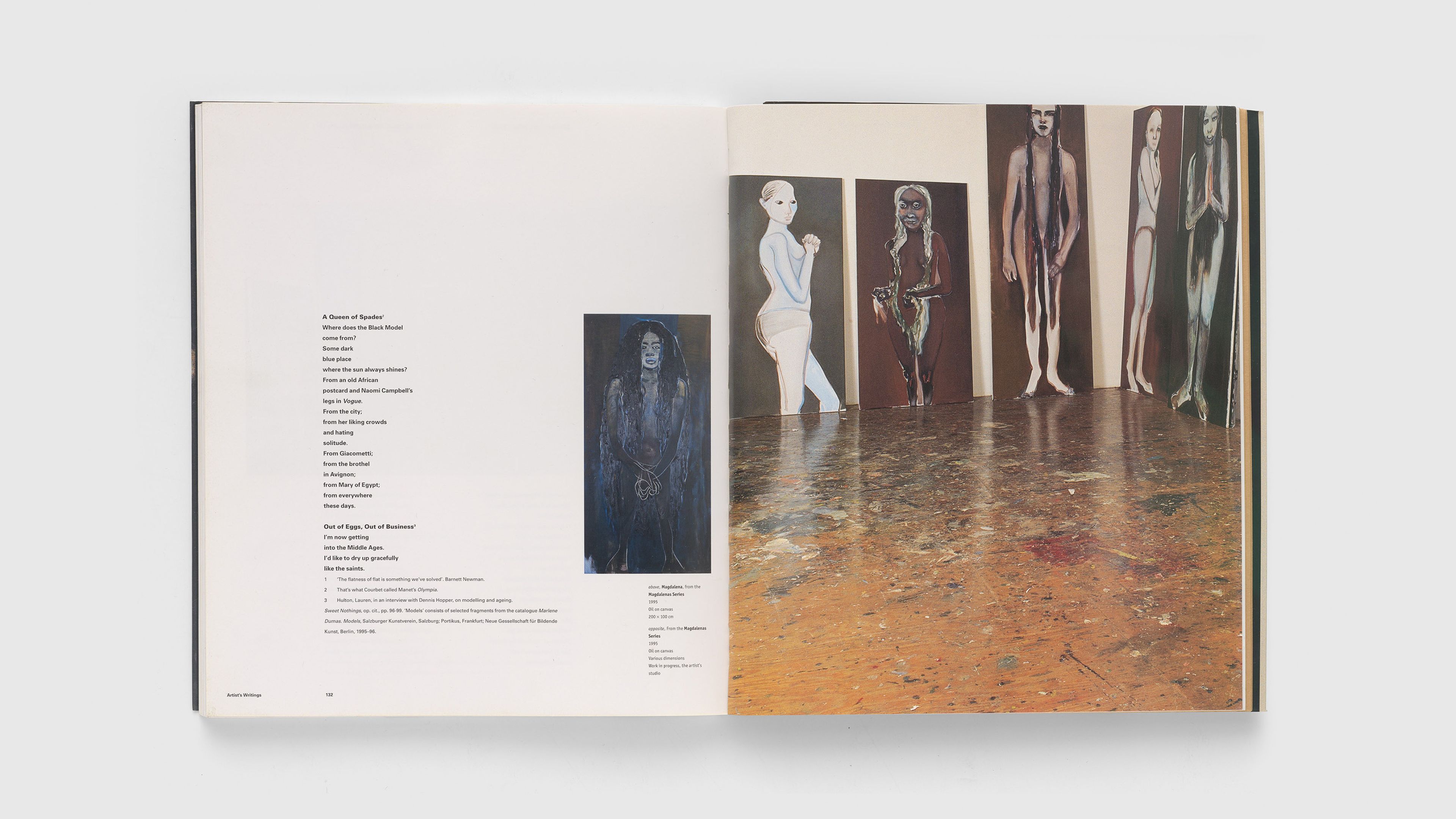

A spread from Marlene Dumas, 1999, showing selected Magdalena paintings in the artist's studio in 1995, including the present work at far right.

José de Ribera, St. Agnes in Prison, 1641. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Saxony, Germany

Tilman Riemenschneider, Elevation of St. Mary Magdalene, c.1490/1492. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich

Guido Reni, Saint Mary Magdalene, c.1634–1635 (detail). The National Gallery, London

Dumas’s “imagined beings” draw from a broad range of sources, including devotional images and photographs of present-day supermodels. In the artist’s own words, “The Magdalenas were constructed by using parts of supermodels’ bodies and parts (and poses) of old paintings of women. It’s like Madonna choosing this name for her singing career. She’s not trying to be the real Madonna from the bible, but it helps."

For this work, Dumas was in part inspired by José de Ribera’s painting Saint Agnes in Prison (1641; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden) as well as by sculpted depictions of Mary Magdalene, like those by Northern Renaissance sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider.

In these works, Dumas deepens her dialogue with art history through one of its most prolific genres: the female nude. These images recast a Biblical figure in a manner that is both unflinching and contemporary. In contrast with Mary Magdalene’s original association with penitence, Dumas’s women are at once empowered and ambiguous, presenting the female body as an oppositional site of deviance and pleasure, light and dark, concealment and exposure while also questioning notions of gender. Dumas’s use of historical imagery as well as modern-day fashion and advertising sources creates an interplay between modes of female representation over time. As the artist has explained, her work offers “a false sense of intimacy” through these equivocal figures, inviting the viewer into conversation with what they see.

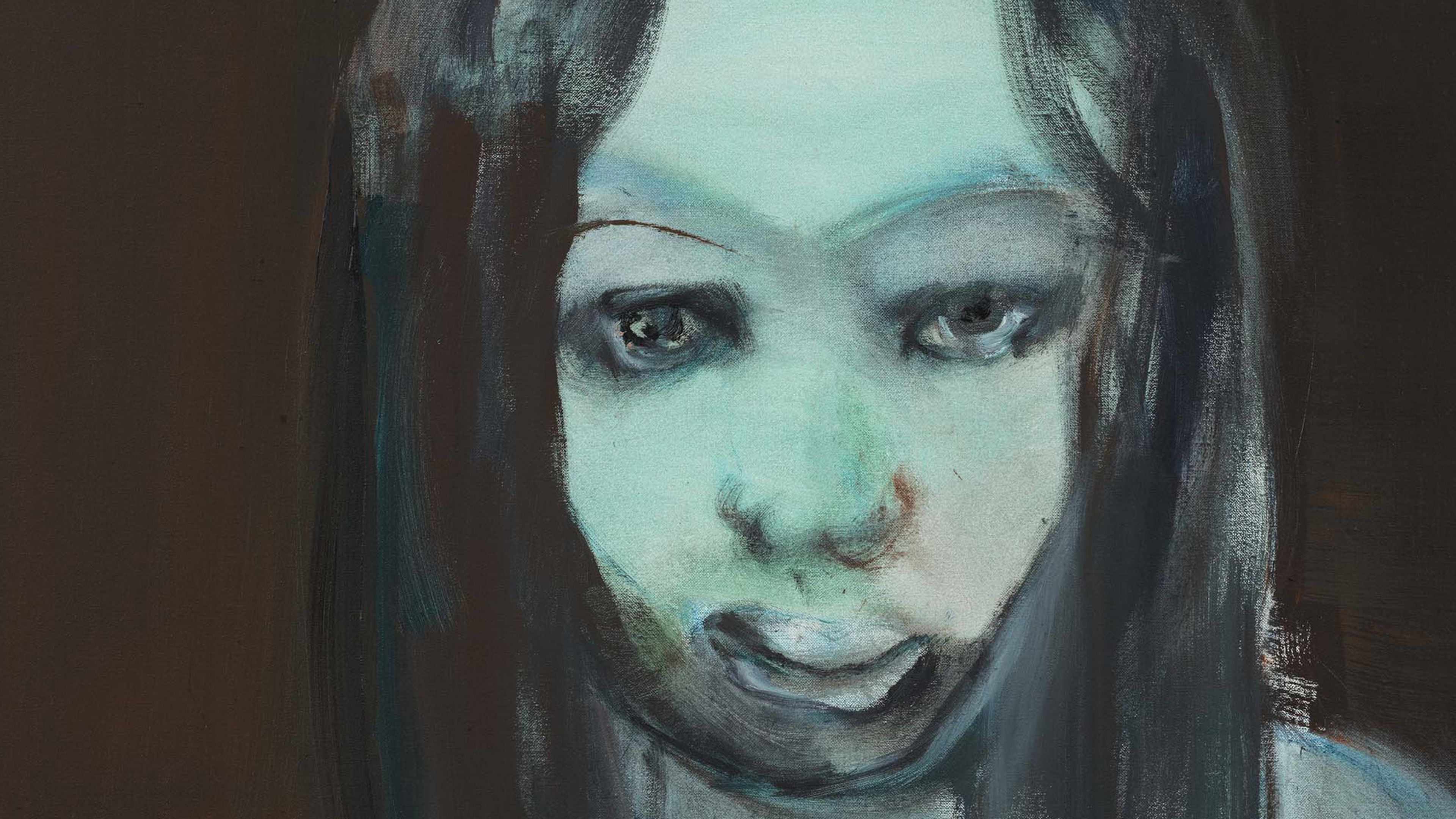

Marlene Dumas, Magdalena, 1995 (detail)

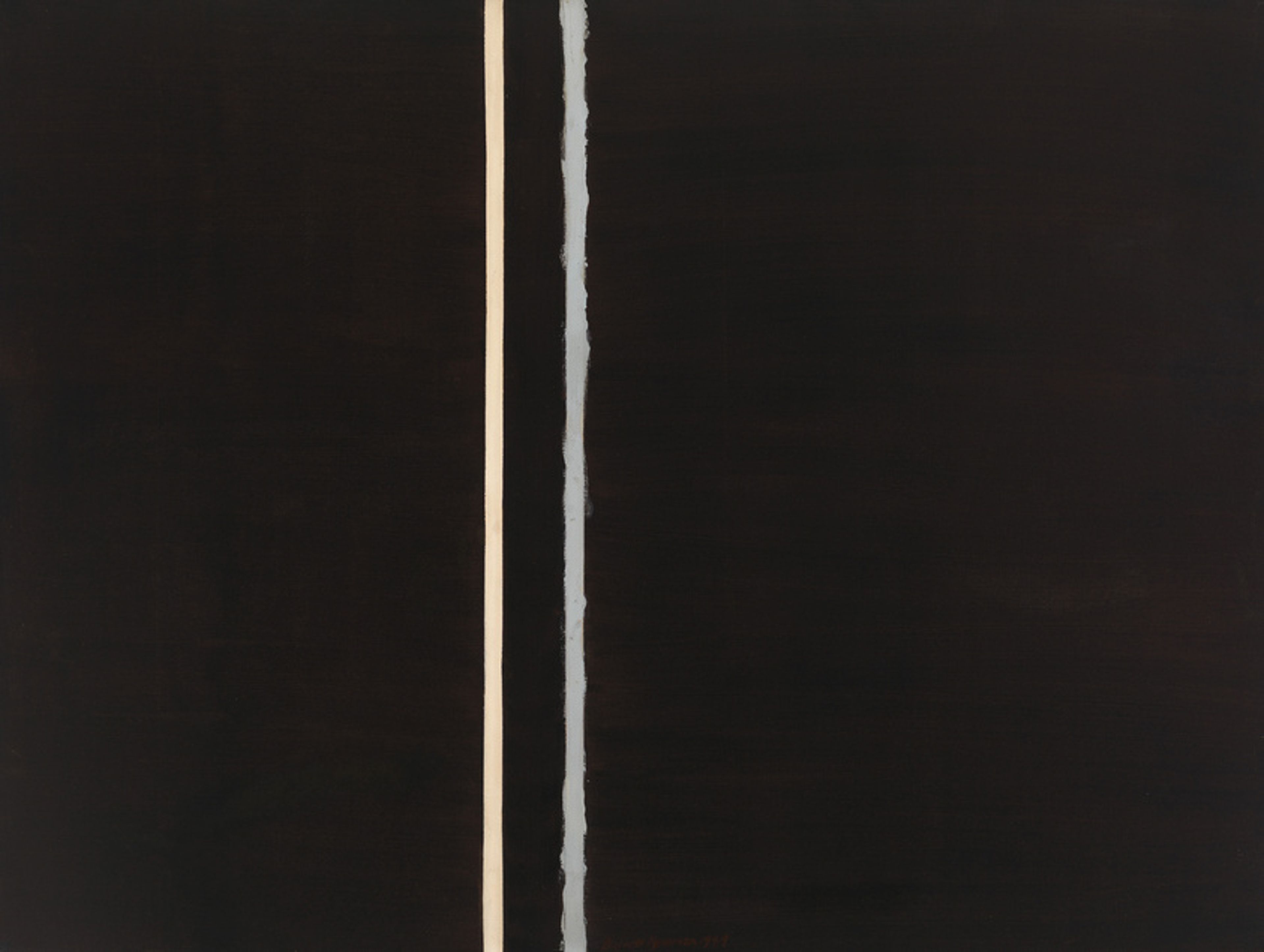

Barnett Newman, The Promise, 1949. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © 2025 The Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Describing the formal quality of these intensely vertical figures, Dumas has referenced Barnett Newman’s famous “Zip” paintings in which monochromatic backgrounds are partitioned by narrow vertical bands—or “zips,” as Newman called them—of color.

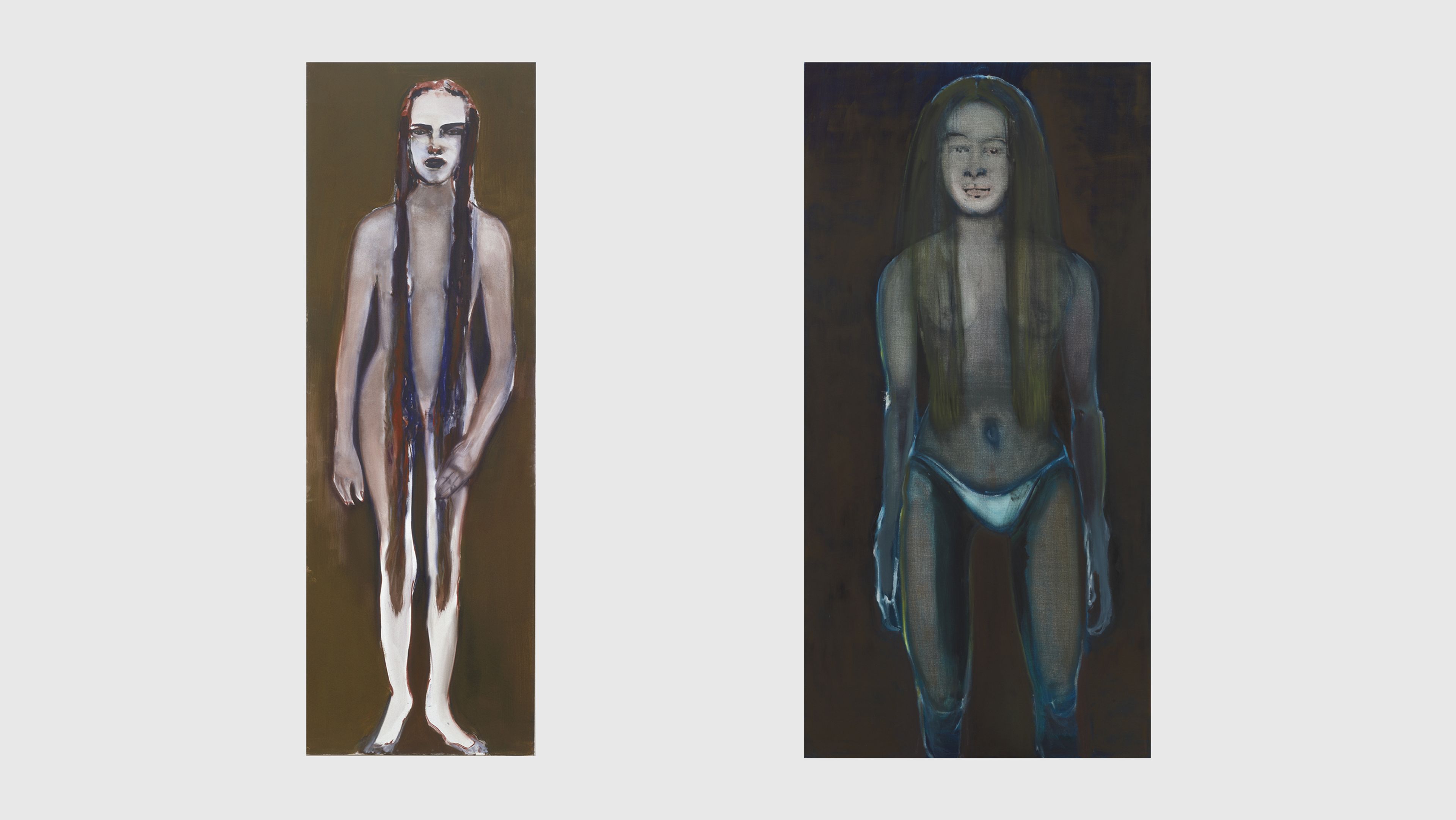

Marlene Dumas, Magdalena (Newman’s Zip), 1995. Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam [left]; Marlene Dumas, Magdalena (Underwear and Bedtime Stories), 1995. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland [right]

Marlene Dumas, Magdalena, 1995 (detail)

David Zwirner at Art Basel