Exceptional Works: Jeff Koons

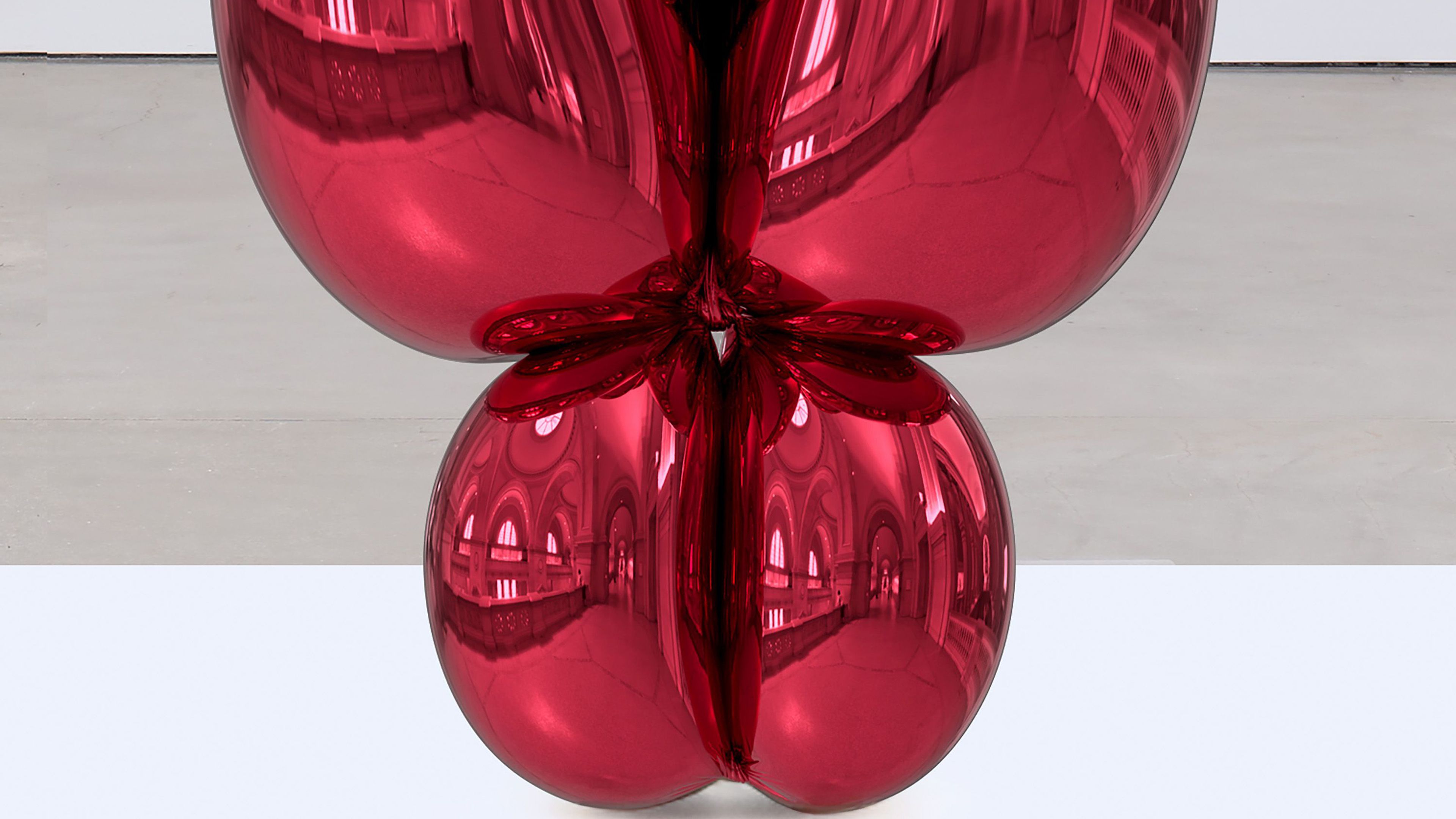

Koons’s 1986 Rabbit represents an important breakthrough in his practice as the first inflatable form to be cast in metal.

Jeff Koons, Aqualung, 1985

Koons’s broader engagement with inflatable forms dates to the late 1970s. For his first mature body of work, Inflatables, he placed small blow-up flowers in mirrored tableaux. In 1986, Koons created his now-canonical Rabbit, his first inflatable form to be rendered in highly reflective stainless steel.

The female Venus form started appearing in Koons’s work in the late 1970s, and he sees Snorkel Vest and Aqualung (both 1985) as feminine and masculine representations of the Venus of Willendorf. “Looking at these sculptures of inflatable life-saving devices, you become aware of their anthropomorphic aspects,” the artist says. “Certain works of mine have a dialogue with time and space through the references of human history and my Venus sculptures are an example of those.”

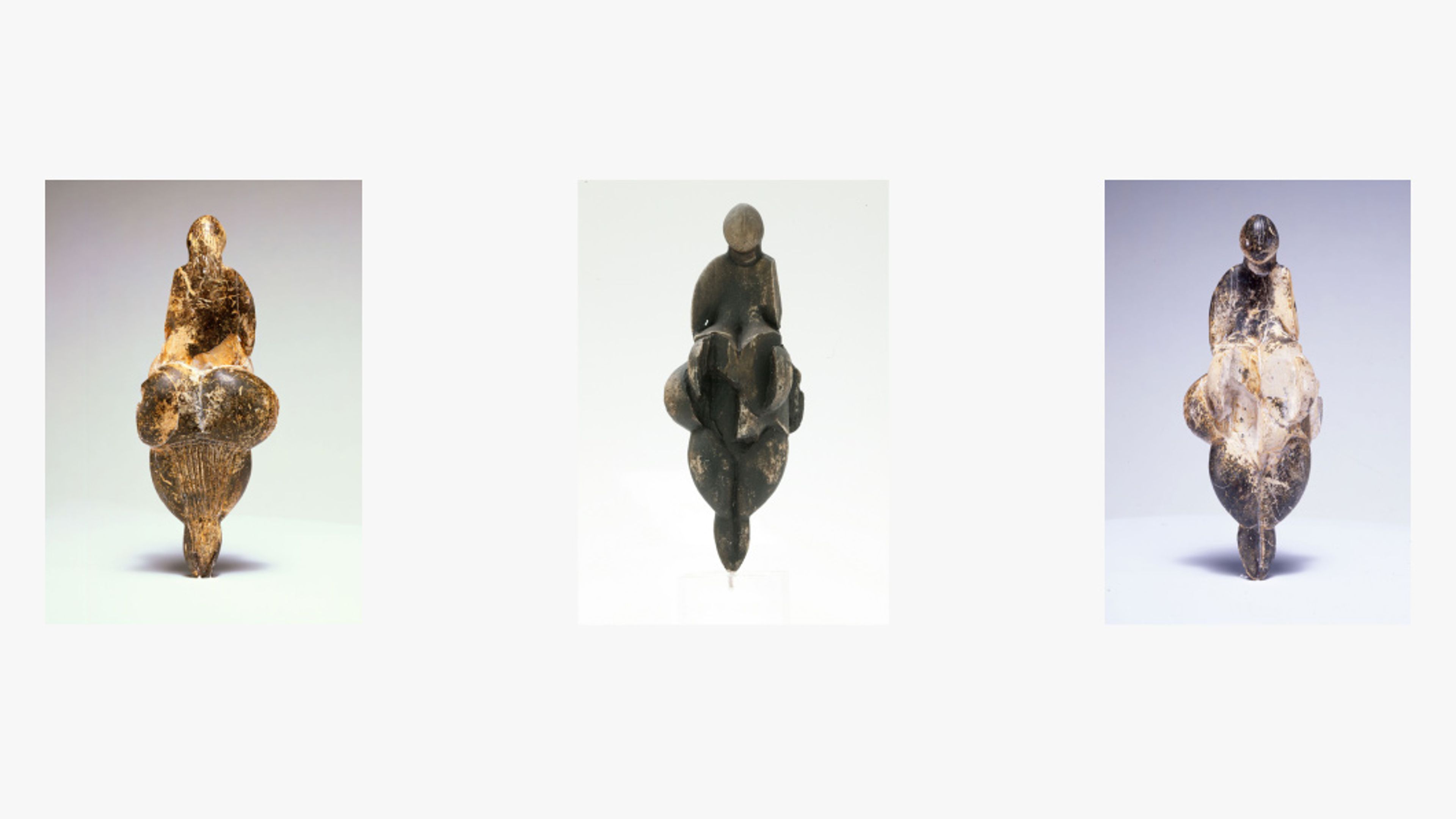

Left and Right: Vénus de Lespugue. Mammoth ivory. Upper Paleolithic, c. 23000 BC. Musée de l'Homme, Paris Photo © JC Domenech / MNHN, Paris.

Venus of Willendorf. Limestone. Stone Age, Aurignacien, 28000–25000 BC. Photo © Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Constantin Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany II, 1920. Albright-Knox Art Gallery / Art Resource, NY. © ARS, NY

Jeff Koons, Gazing Ball (Crouching Venus), 2013

In its geometric form, the artist’s interpretation of the Venus of Lespugue statuette—which dates back twenty-four to twenty-six thousand years and was discovered in a Pyrenean cave in 1922—draws associations to modernist sculpture, thus invoking long-standing debates about the beginnings of abstraction in art.

By interpreting the already abstracted Venus figure as a large-scale balloon sculpture, Koons heightens the play between abstraction and figuration, both clarifying and obscuring her form. “I look at it and I think of Brancusi,” says Koons. “I can tie it to the history of modernism.”

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538 (detail). Collection of Uffizi Gallery, Florence © Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY

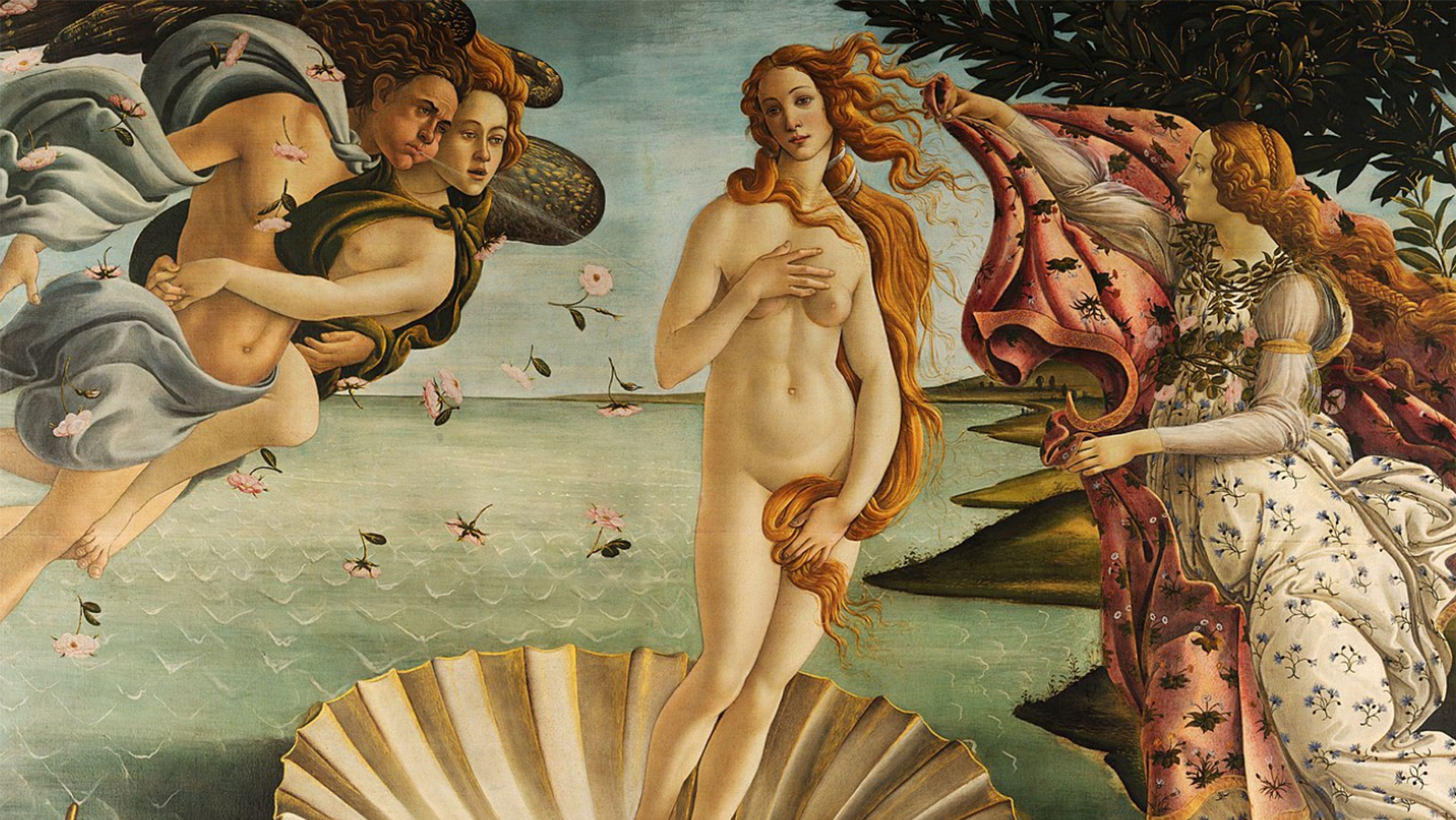

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1484–1486, Collection of Uffizi Gallery, Florence (detail)

Inquire about works by Jeff Koons