Noah Davis

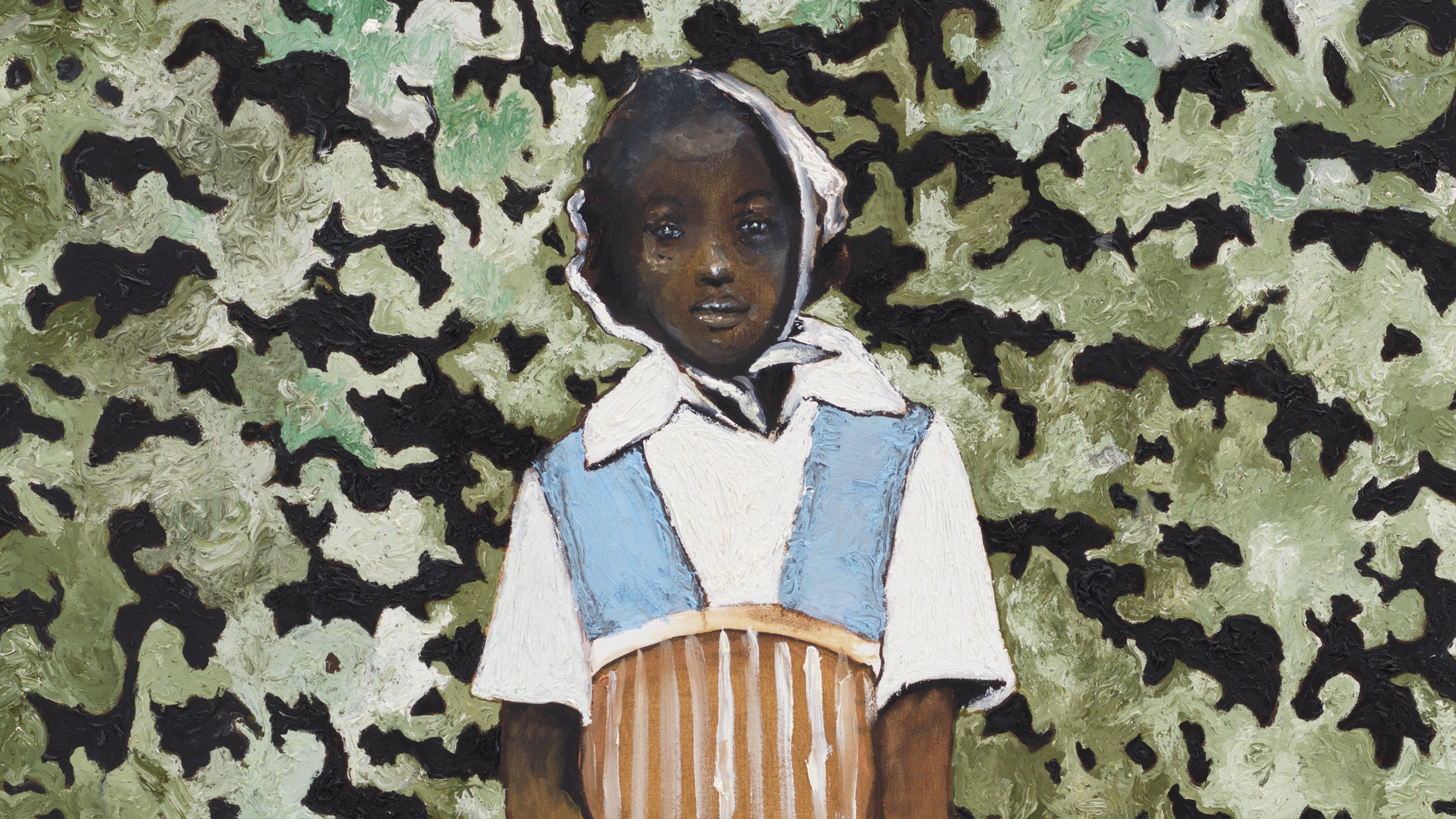

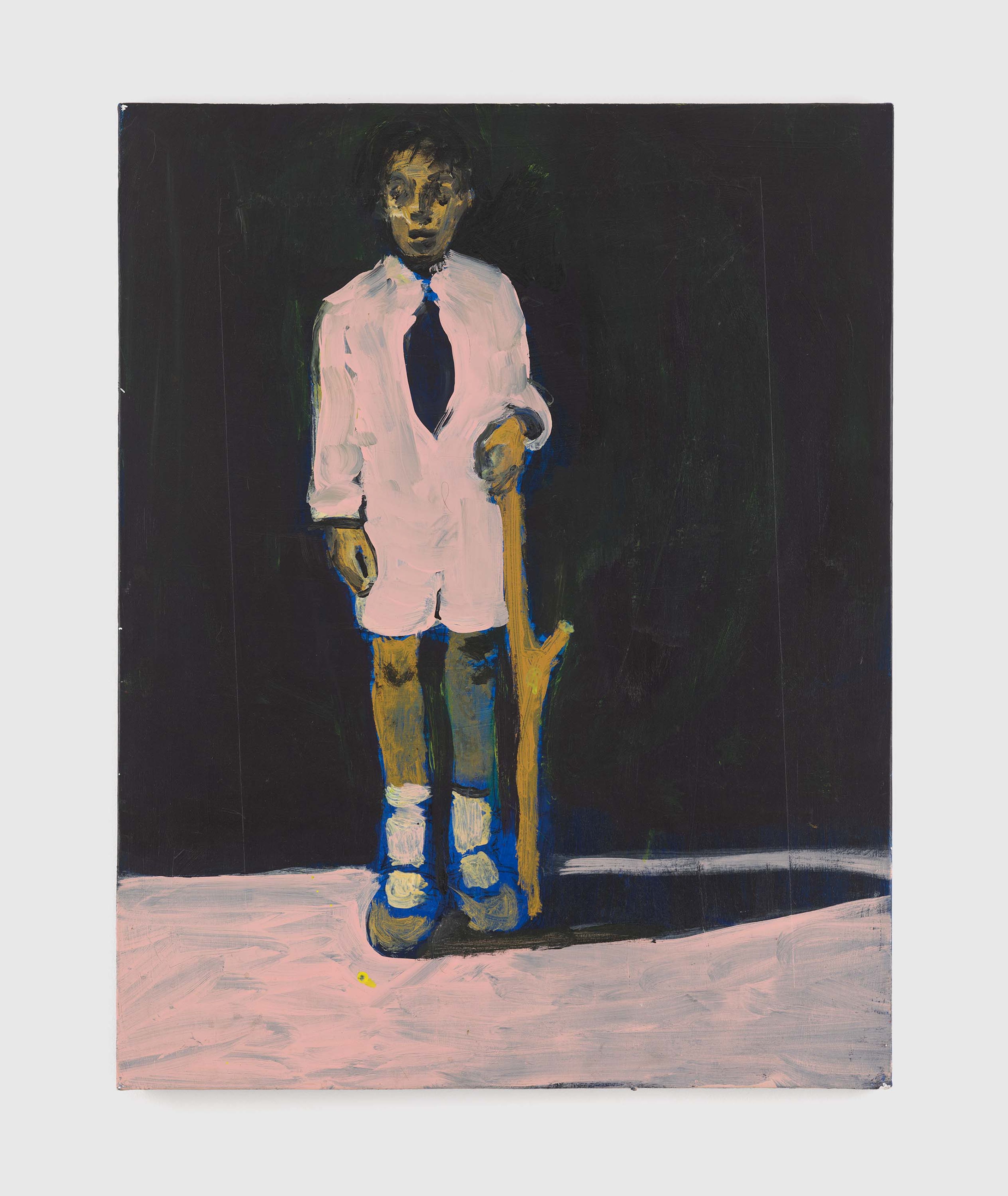

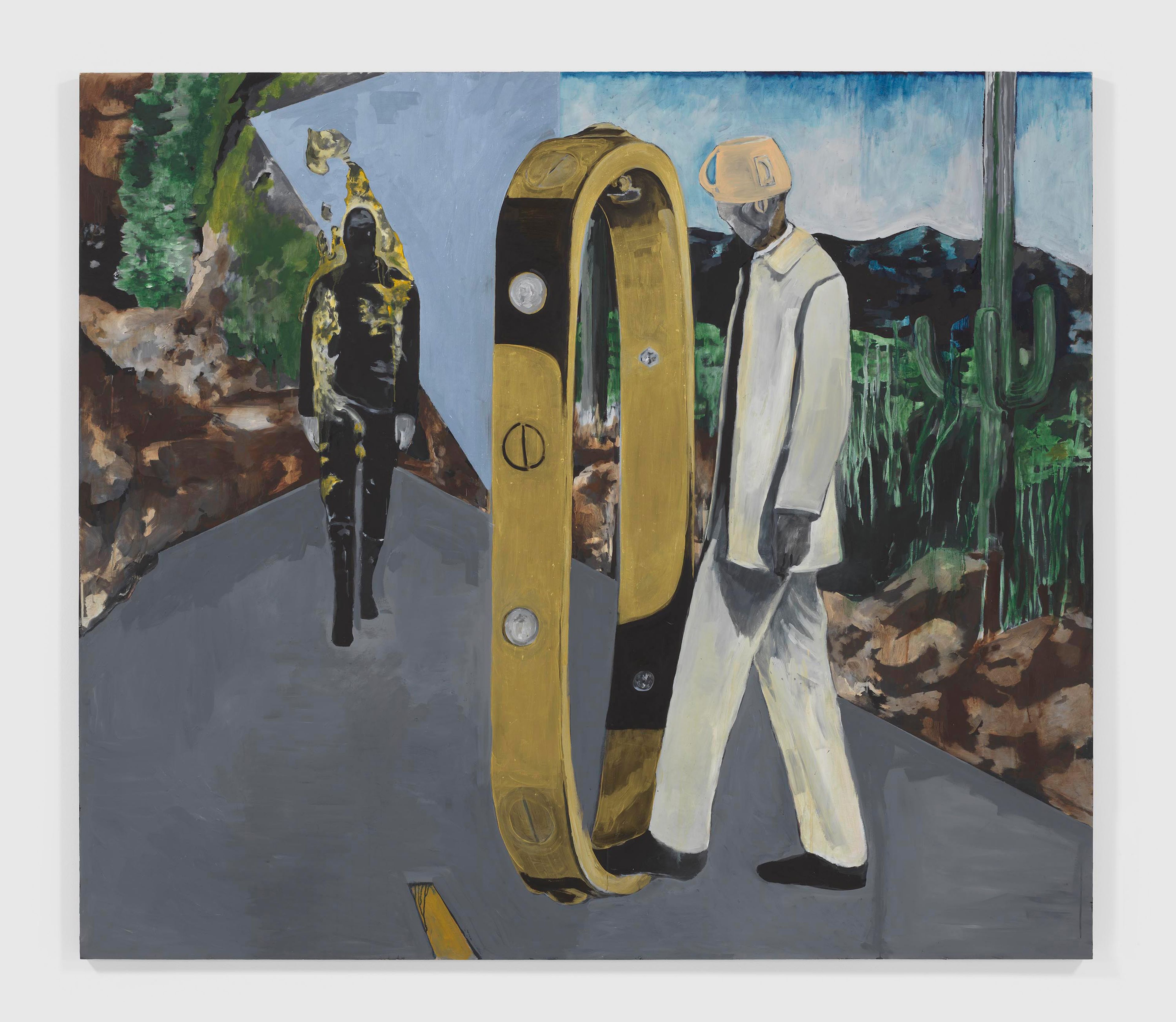

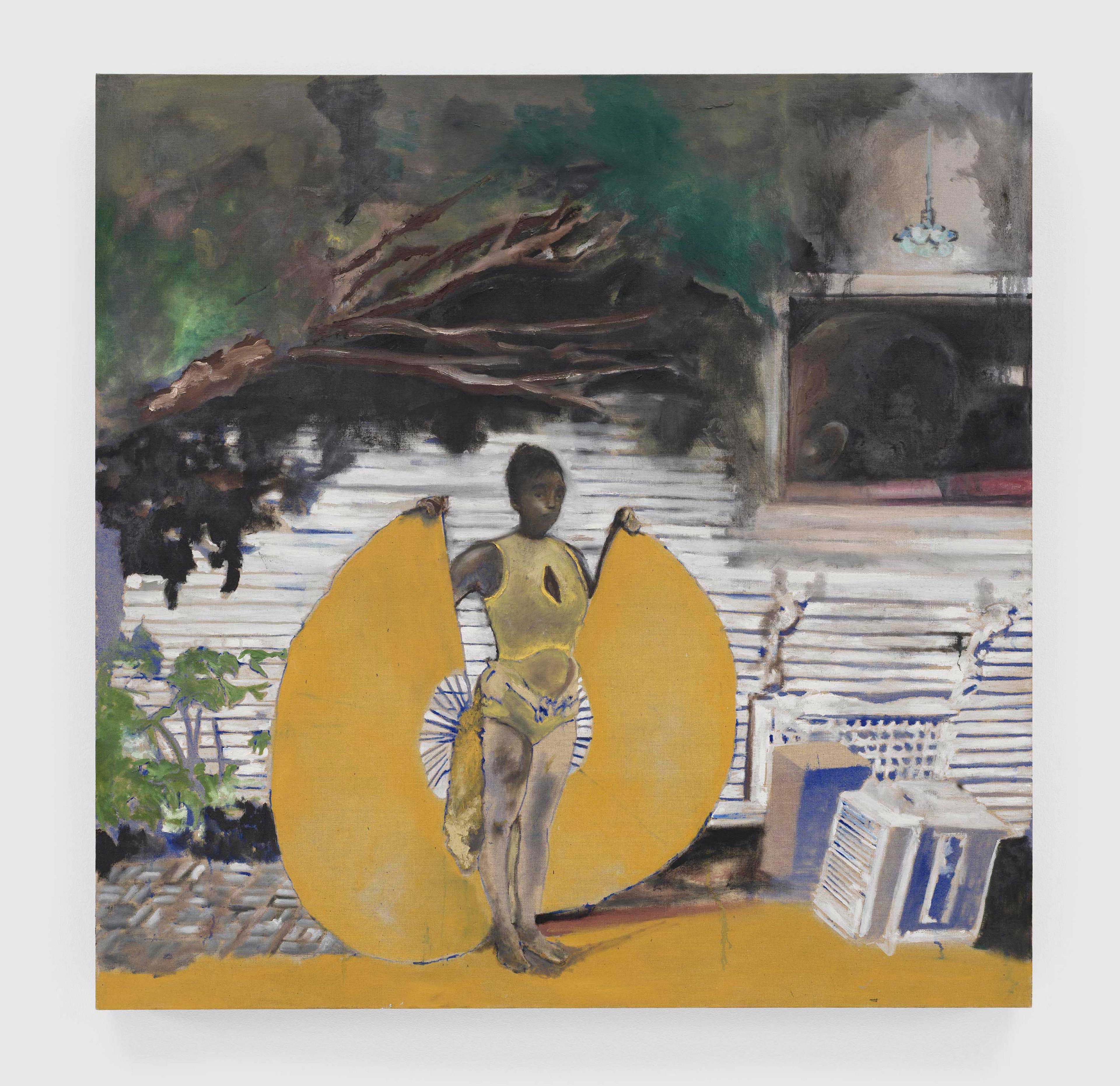

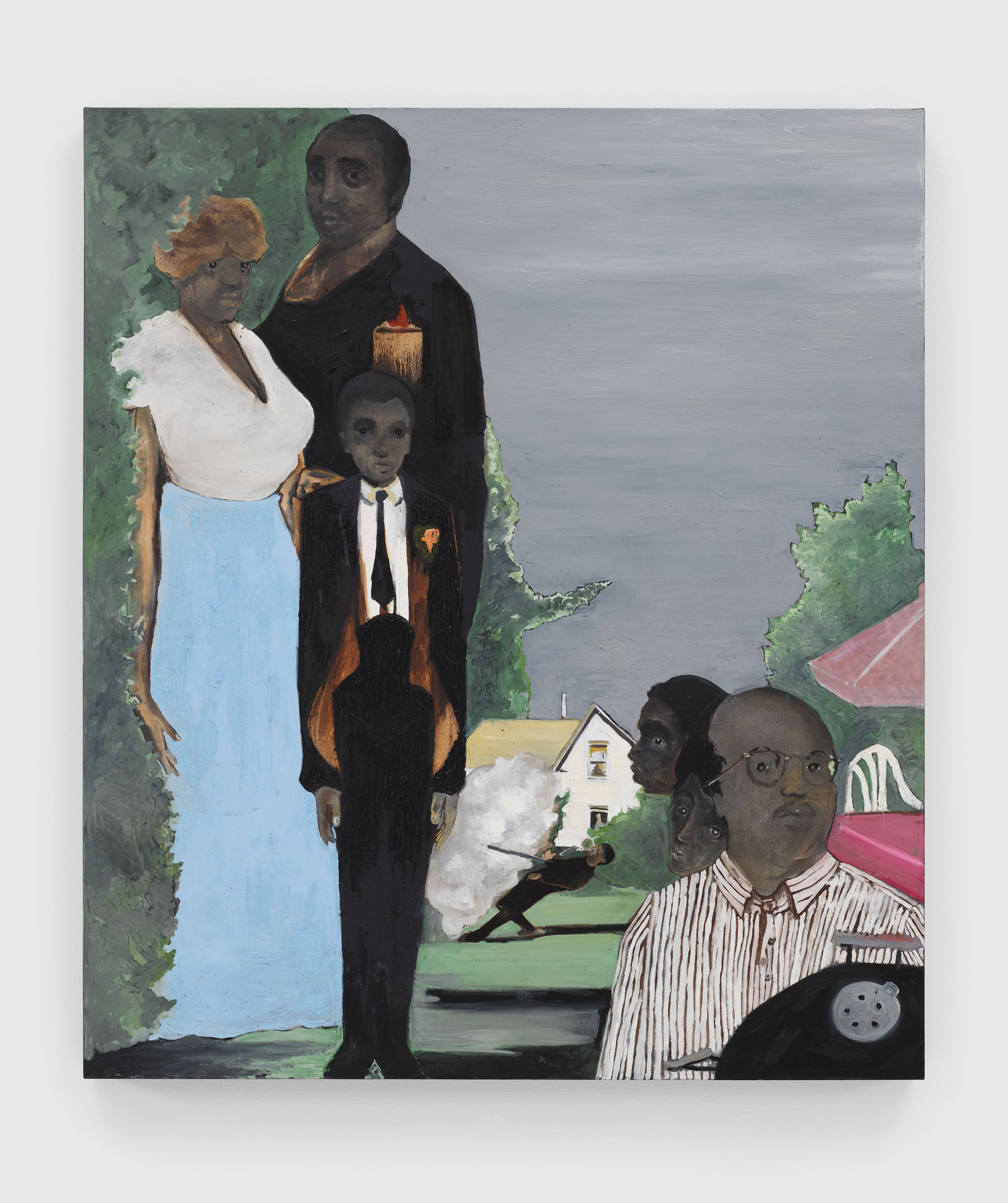

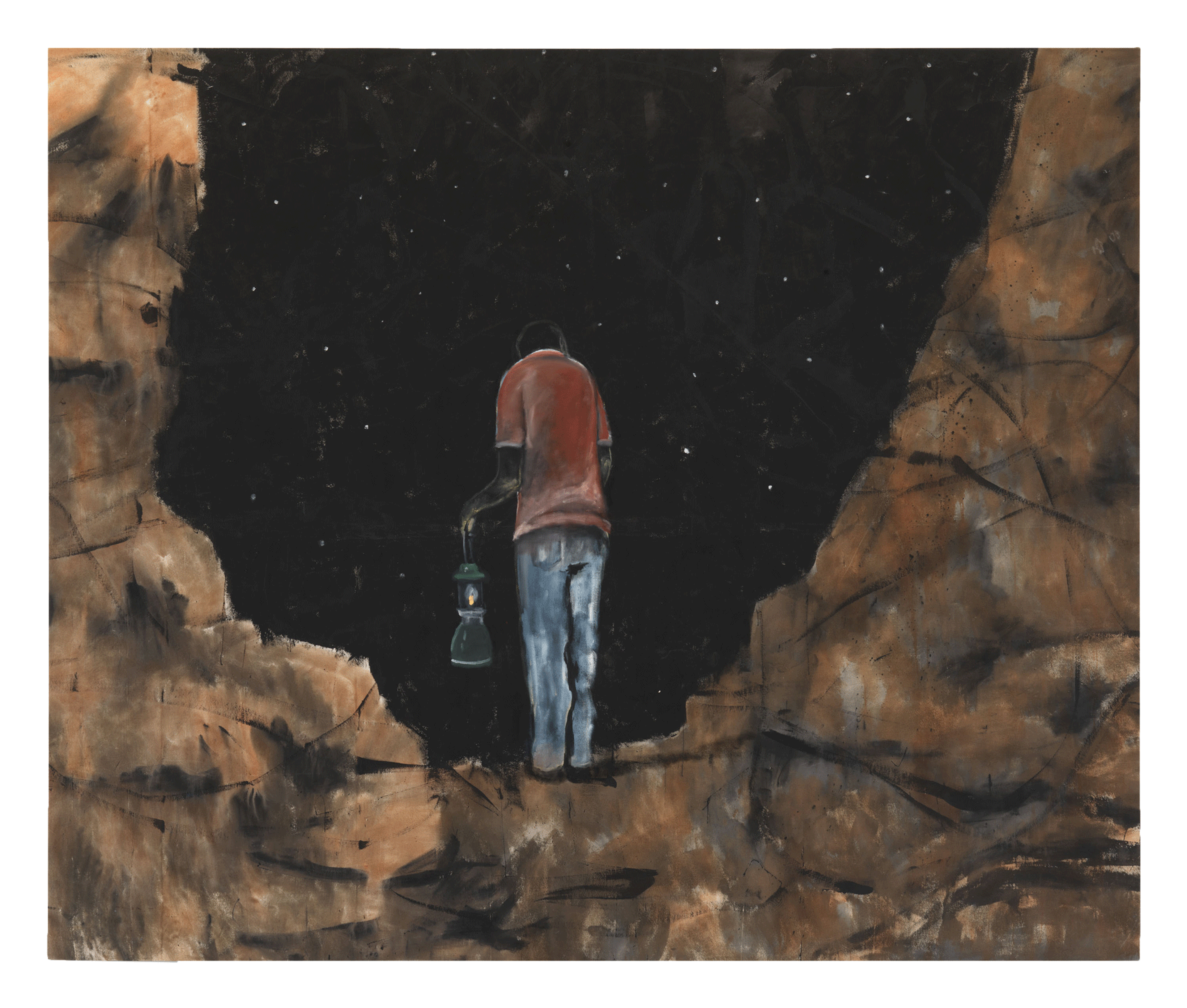

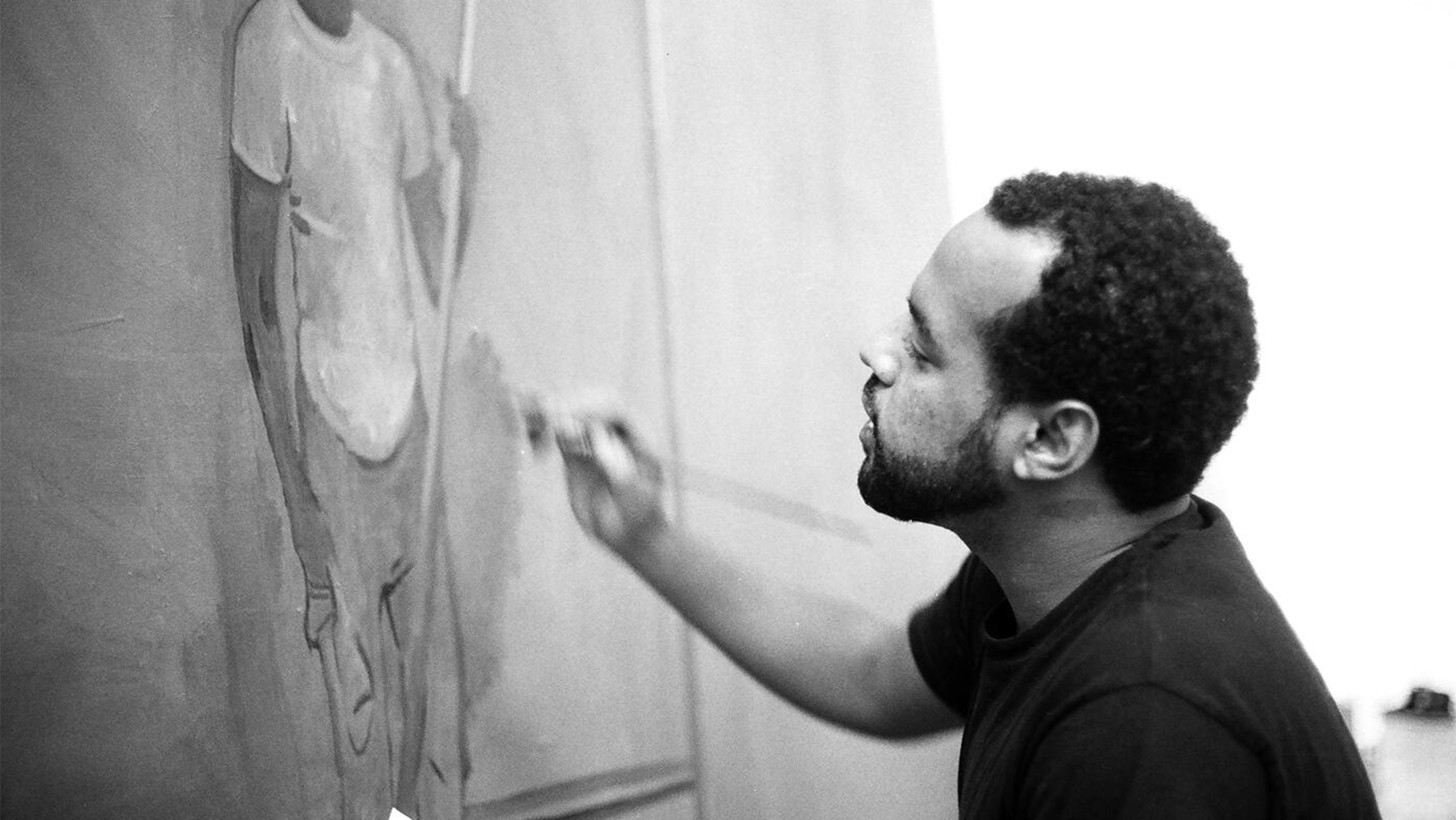

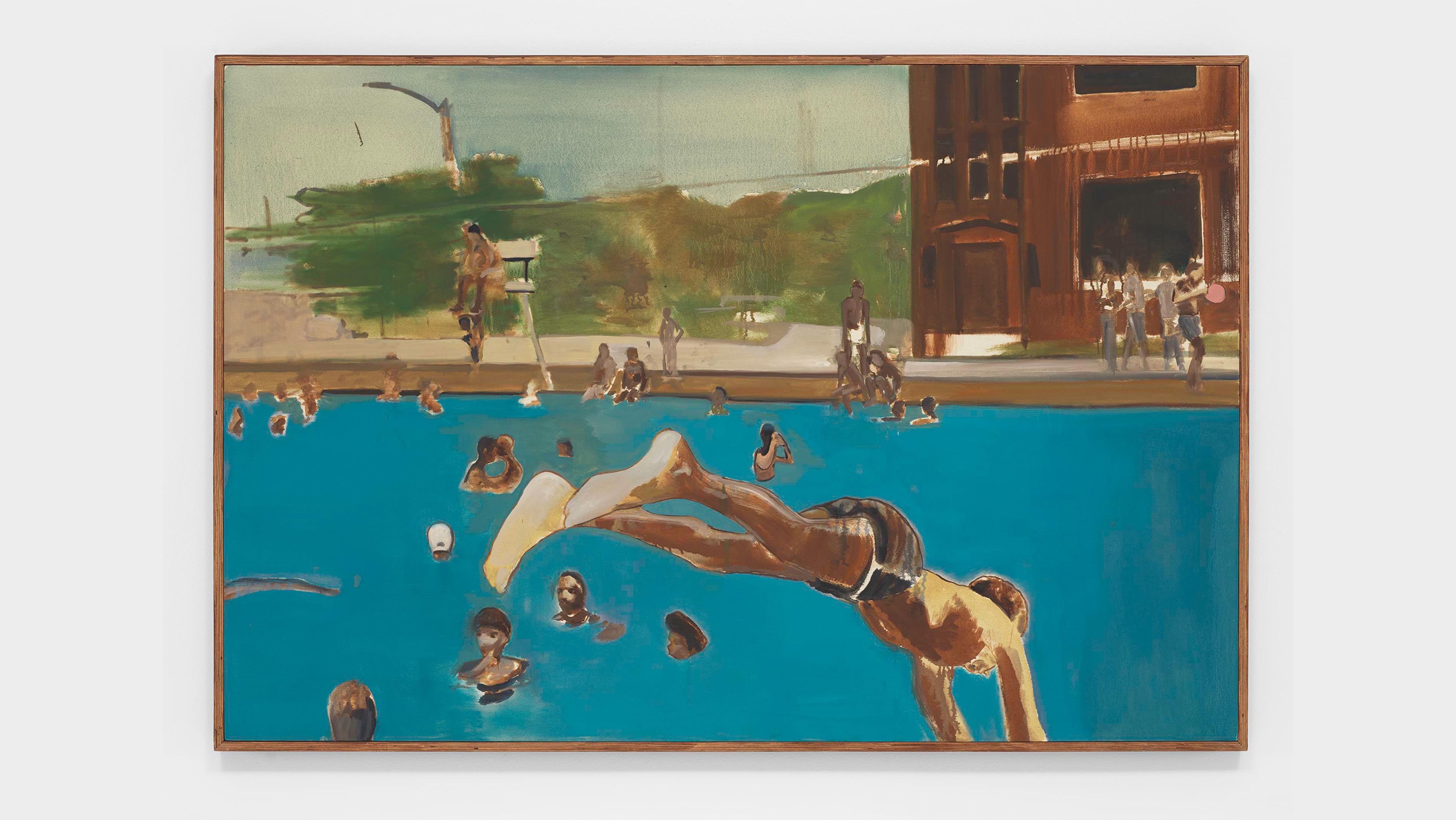

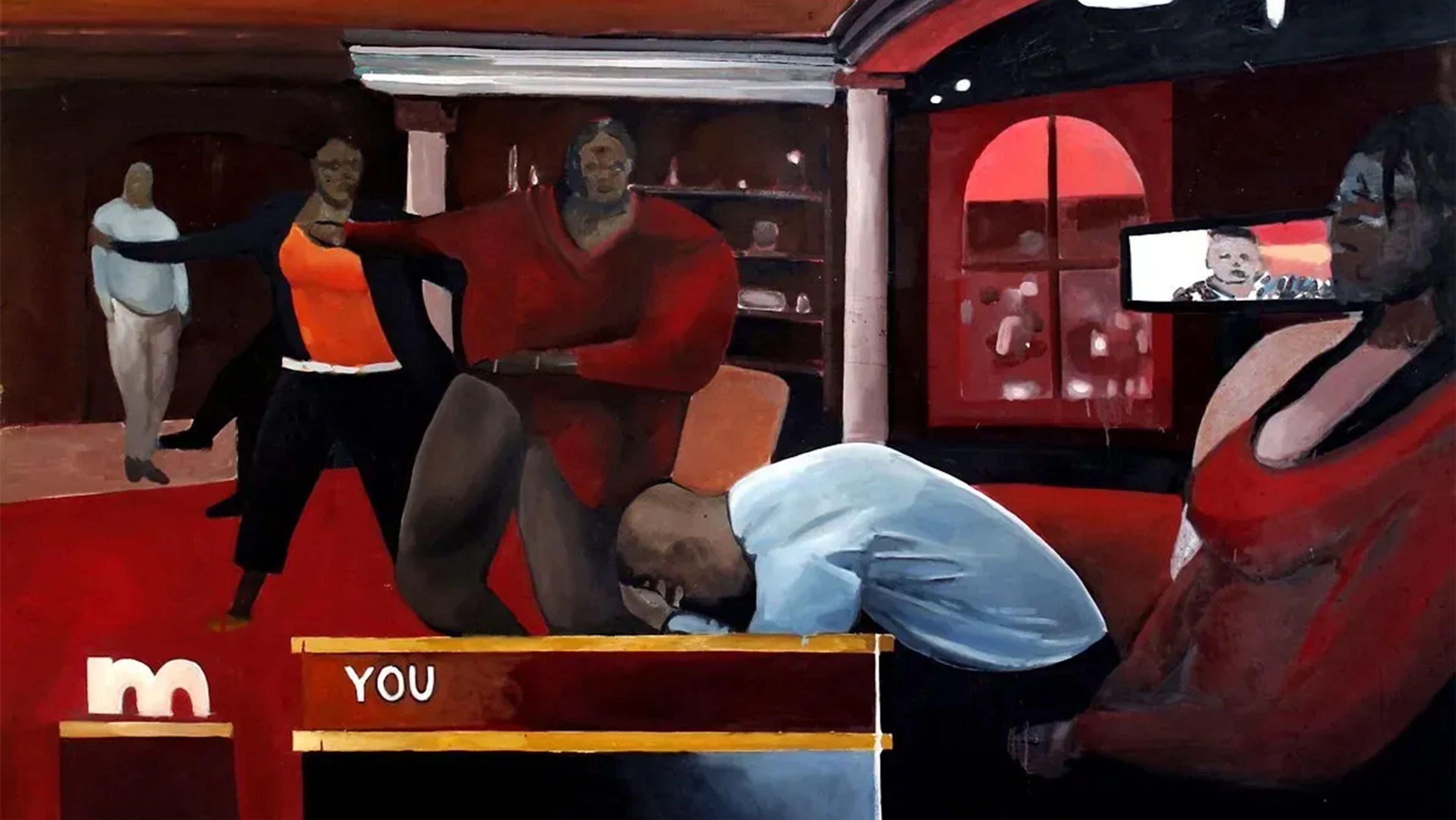

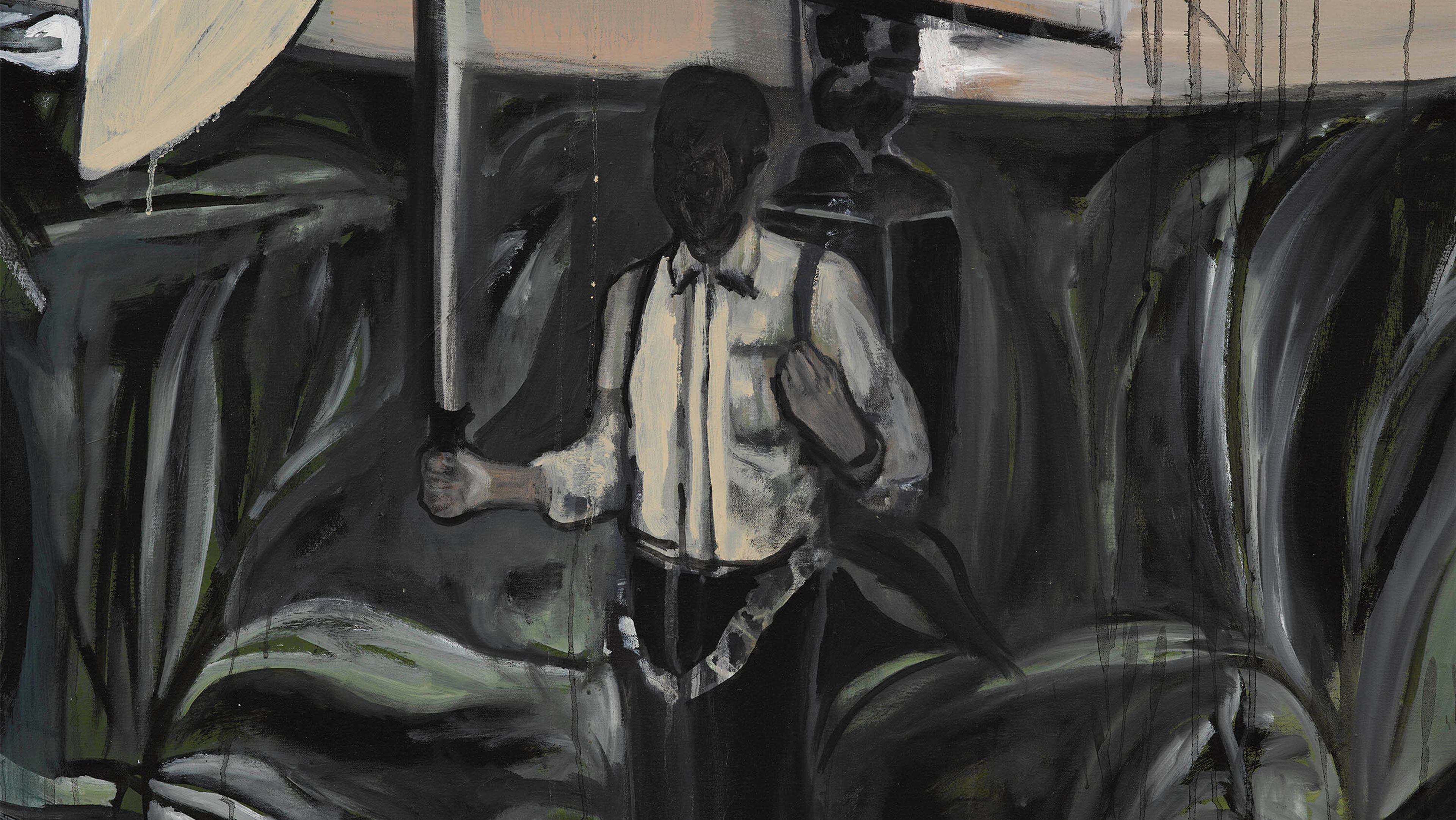

American artist Noah Davis (1983–2015) created a distinctive body of paintings that effortlessly synthesizes a wide range of reference points, pivoting between scenes of everyday life and surreal derivations thereof.

Learn MoreSurvey

Exhibitions

Explore Exhibitions

Artist News

Biography

American artist Noah Davis (1983–2015) created a distinctive body of paintings that effortlessly synthesizes a wide range of reference points, pivoting between scenes of everyday life and surreal derivations thereof. As curator Helen Molesworth describes, “[Davis’s] paintings are both figurative and abstract, realistic and dreamlike; they are about blackness and the history of Western painting, drawn from photographs and from life; they are exuberant and doleful in their palette, influenced by European painters Marlene Dumas and Luc Tuymans, as well as American ones such as Mark Rothko and Fairfield Porter. They tend toward the ravishing. A master of sophisticated compositions, he had a knack for establishing three-dimensional space while remaining highly attuned to the flatness of the canvas.”1

Born in Seattle, Davis studied painting at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York before moving to Los Angeles, where, in 2012, he founded The Underground Museum in the city’s Arlington Heights neighborhood with his wife and fellow artist, Karon Davis.

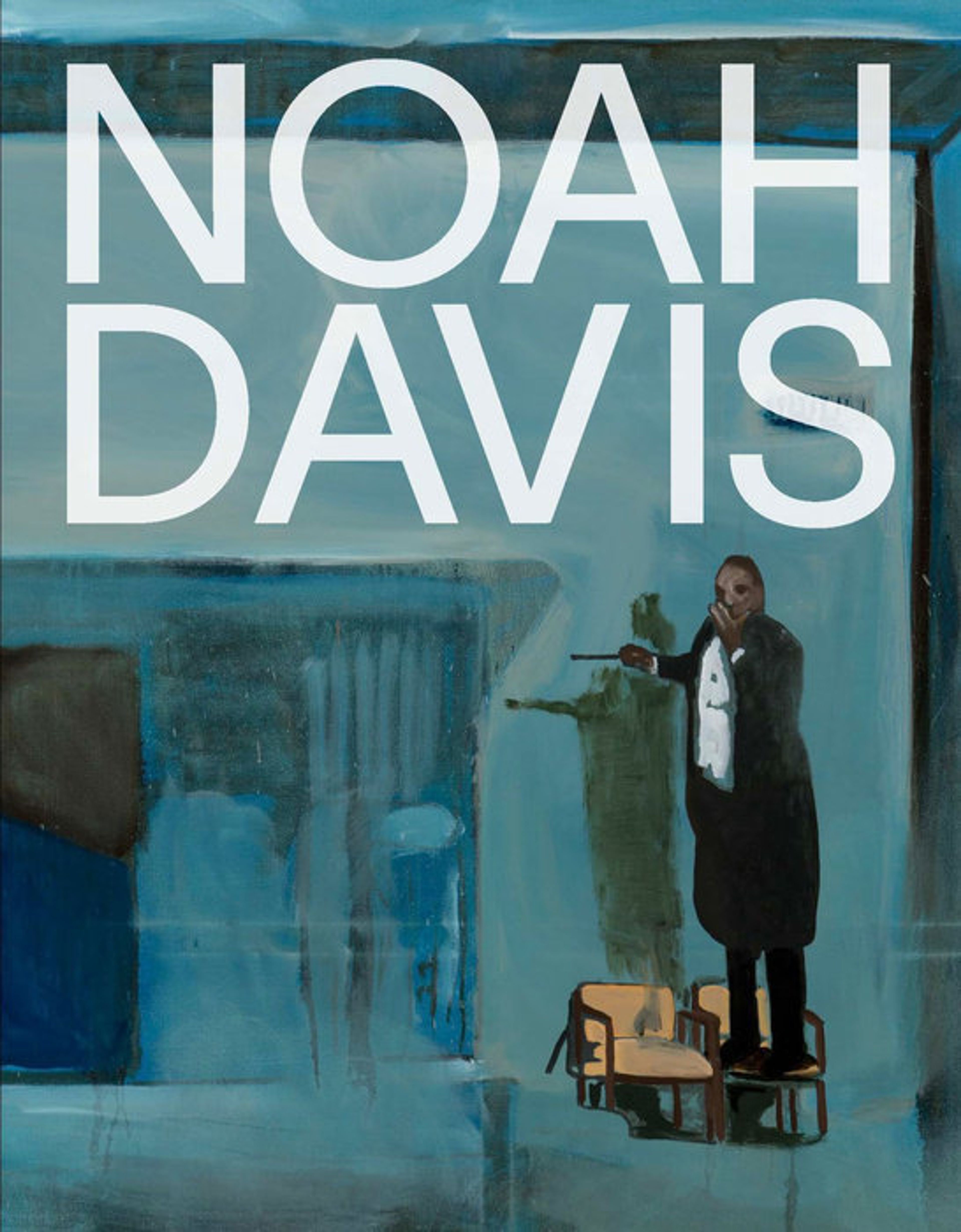

Davis’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California (2008, 2010, and 2013); Tilton Gallery, New York (2009 and 2011); PAPILLION, Los Angeles (2014); and the Rebuild Foundation, Chicago (2016), among others. Noah Davis: Imitation of Wealth opened at The Underground Museum on the day of the artist’s untimely death at age thirty-two, due to complications from a rare cancer. In 2016, the Frye Art Museum, Seattle, presented the two-person exhibition Young Blood: Noah Davis, Kahlil Joseph, The Underground Museum—the first large-scale museum show to explore Davis’s work alongside that of his brother’s. In 2020, an acclaimed solo presentation of Davis’s work went on view at David Zwirner, New York, later traveling to The Underground Museum, Los Angeles, in 2022. A retrospective of Davis’s work is currently on view at the Philadelphia Art Museum. The exhibition was previously presented at DAS MINSK Kunsthaus, Potsdam, Germany (2024); Barbican Art Gallery, London (2025); and Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2025).

In 2022, a selection of the artist's work was presented at the 59th Venice Biennale. The artist’s work was featured in the landmark exhibition 30 Americans, which was organized by the Rubell Family Collection, Miami, and traveled extensively throughout the United States from 2008 to 2022. Davis’s work has been included in other notable group exhibitions, including ones held at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California (2010 and 2020); The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2012 and 2015); Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh (2017); Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), North Adams (2018); and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2024). Davis's work was featured in the traveling exhibition, The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure, which was first presented at the National Portrait Gallery, London (2024), then traveled to The Box, Plymouth, England (2024); Philadelphia Museum of Art (2024-2025); and the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh (2025).

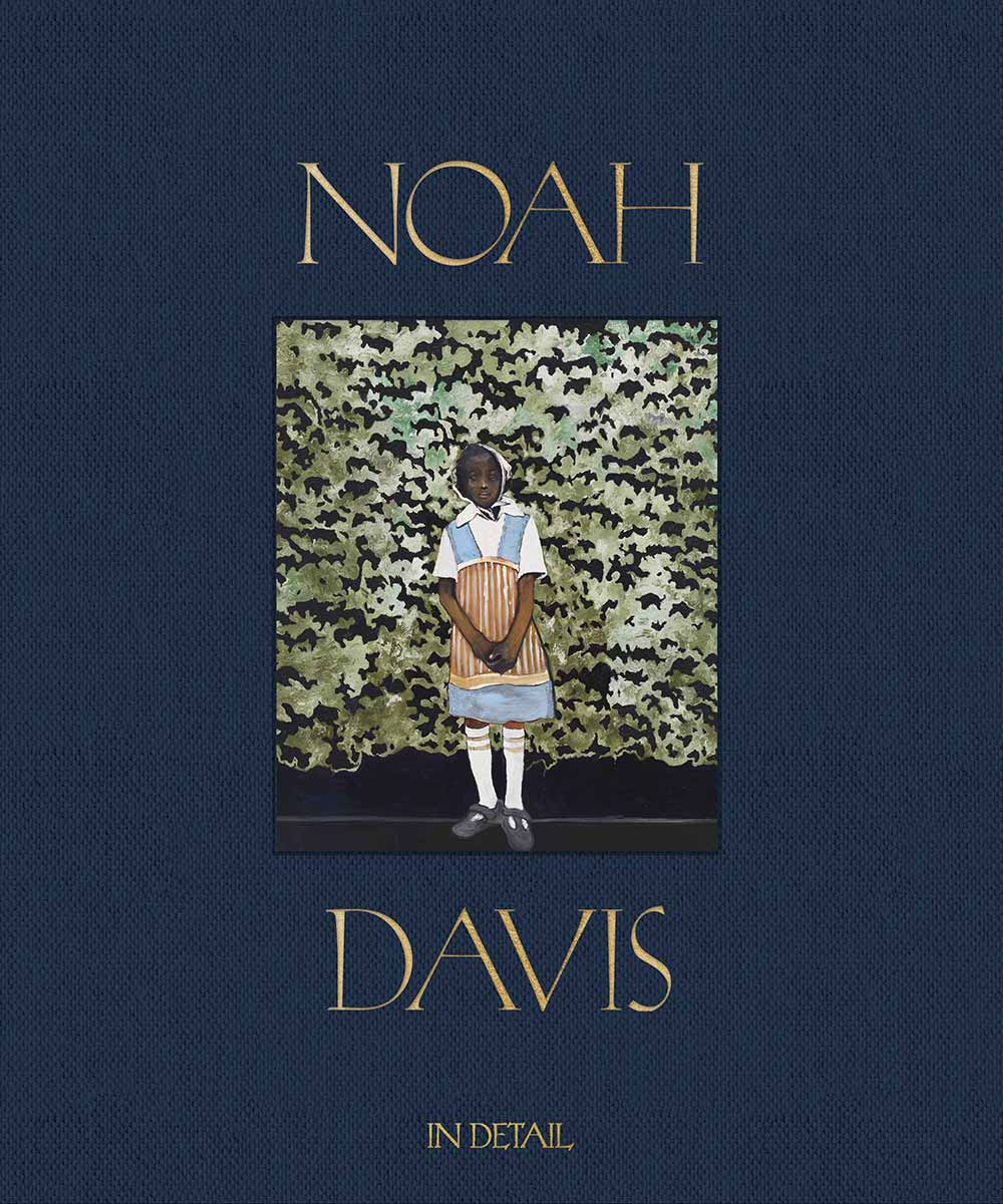

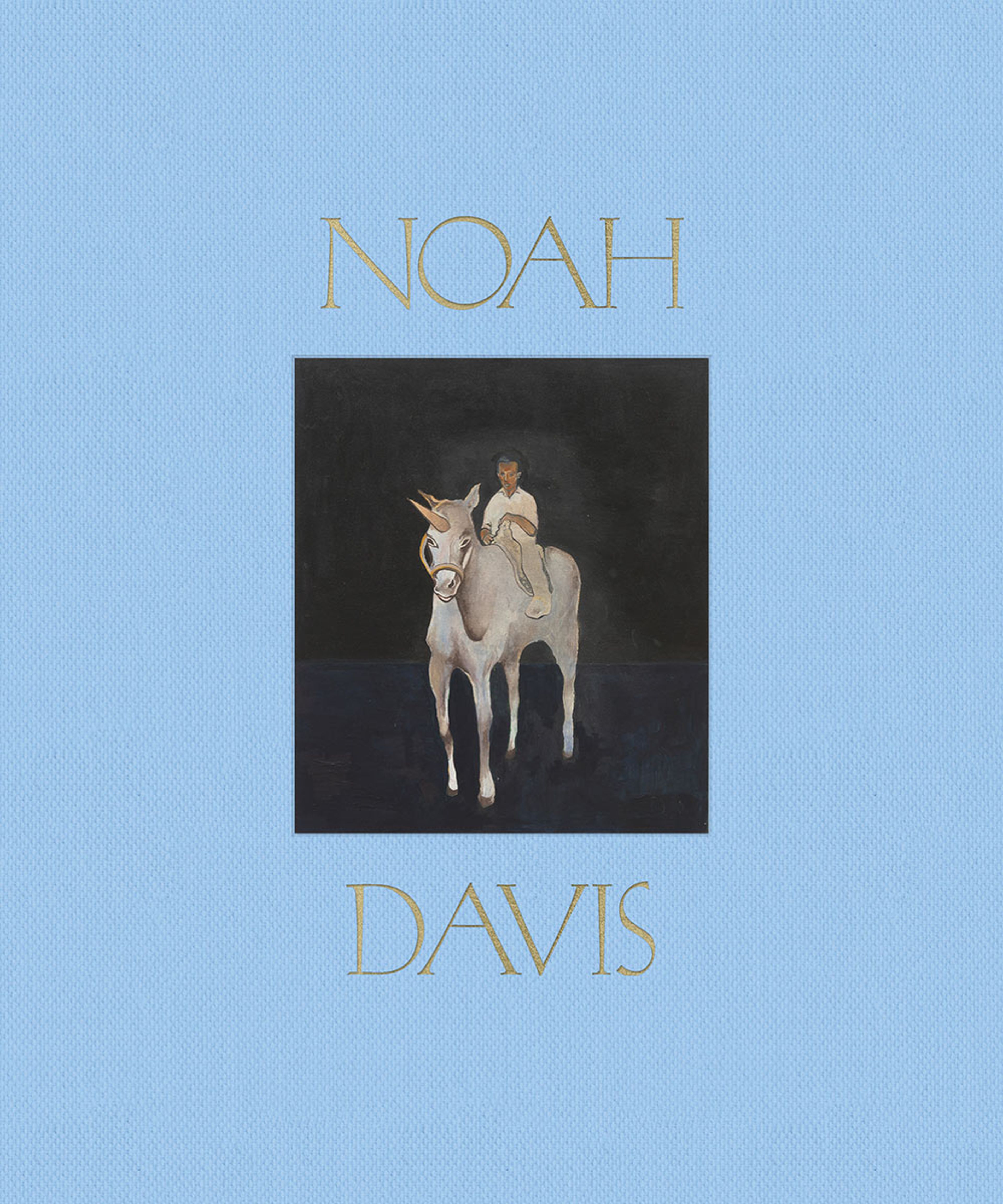

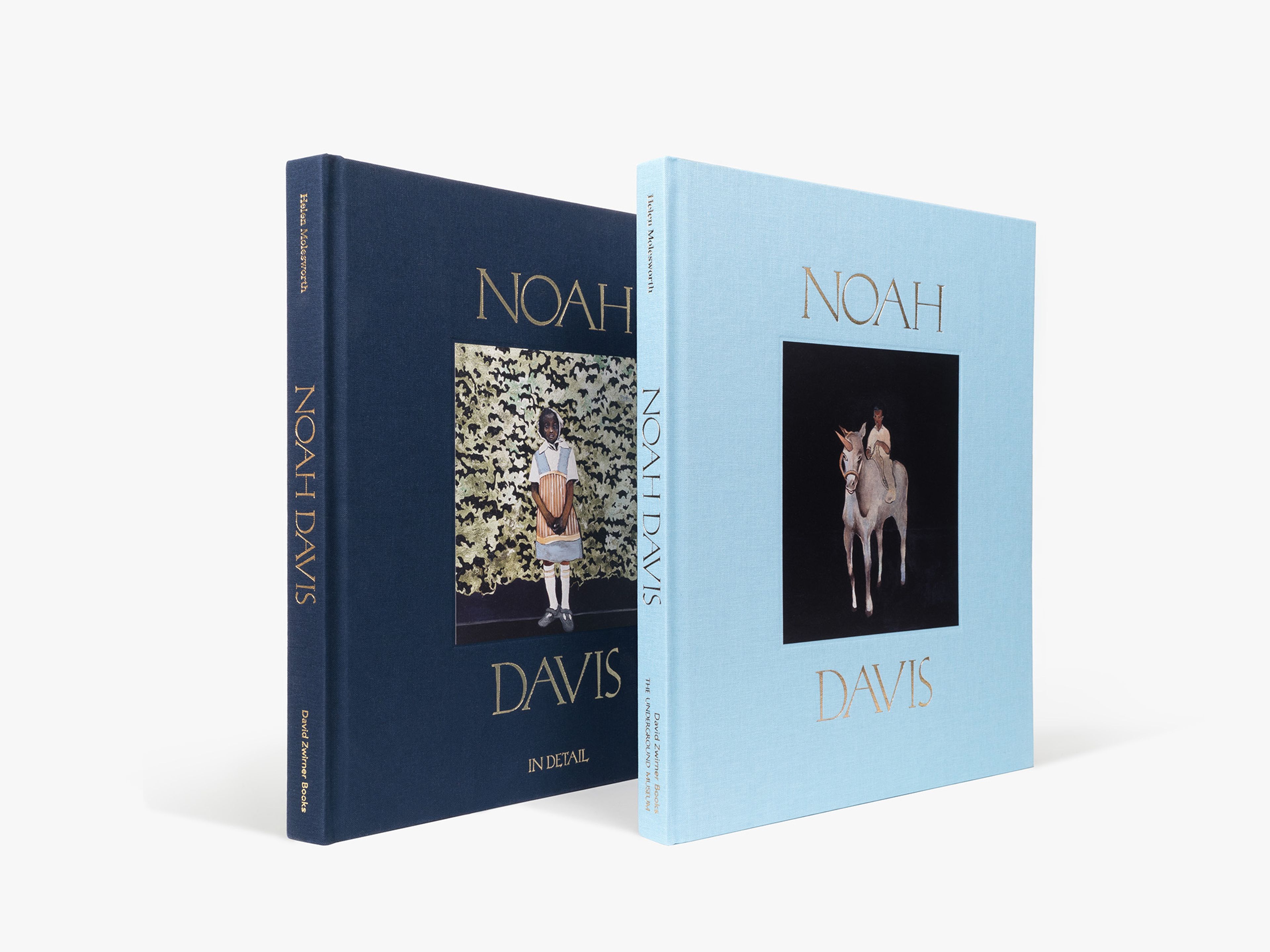

In 2021, David Zwirner, London, presented a solo exhibition of the artist’s work, providing an overview of Davis’s brief but expansive career. A monograph, Noah Davis: In Detail, from David Zwirner Books, was published on the occasion of the exhibition, featuring a new essay by curator Franklin Sirmans; a roundtable discussion with curator Thomas Lax, artists Glenn Ligon and Julie Mehretu, and poet and scholar Fred Moten, moderated by Helen Molesworth; and an extensive new chronology by Lindsay Charlwood. Noah Davis: Ancient Reign, a solo exhibition of Davis’s work curated by his widow, the artist Karon Davis, was on view at David Zwirner’s 69th Street location in 2024.

Davis was the recipient of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s 2013 Art Here and Now (AHAN): Studio Forum award. Works by the artist are included in the permanent collections of numerous institutions, including the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; Rubell Museum, Miami; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

1 Helen Molesworth, “Noah Davis, An Introduction,” in Molesworth, ed., Noah Davis, exh. cat. (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2020), p. 7.

Selected Press

Selected Titles

Request more information